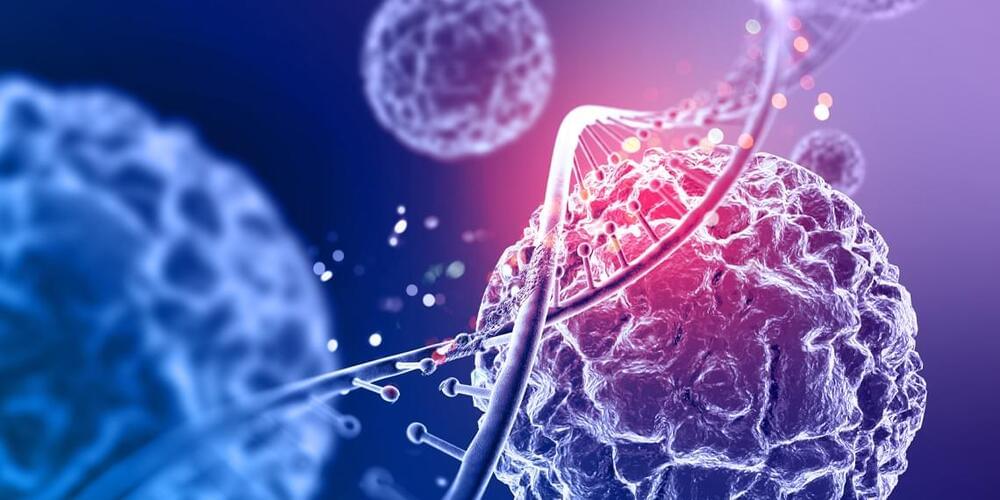

Scientists are shooting stem cells into space, hoping to make discoveries that help people on Earth.

Researcher Dhruv Sareen’s own stem cells are now orbiting the Earth. The mission? To test whether they’ll grow better in zero gravity.

Scientists at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center in Los Angeles are trying to find new ways to produce huge batches of a type of stem cell that can generate nearly any other type of cell in the body — and potentially be used to make treatments for many diseases. The cells arrived over the weekend at the International Space Station on a supply ship.

“I don’t think I would be able to pay whatever it costs now” to take a private ride to space, Sareen said. “At least a part of me in cells can go up!”