Over the last several decades, obesity has rapidly grown to affect more than 2 billion people, making it one of the biggest contributors to poor health globally. Many individuals still have trouble losing weight despite decades of study on diet and exercise regimens. Researchers from Baylor College of Medicine and affiliated institutions now believe they understand why, and they argue that the emphasis should be shifted from treating obesity to preventing it.

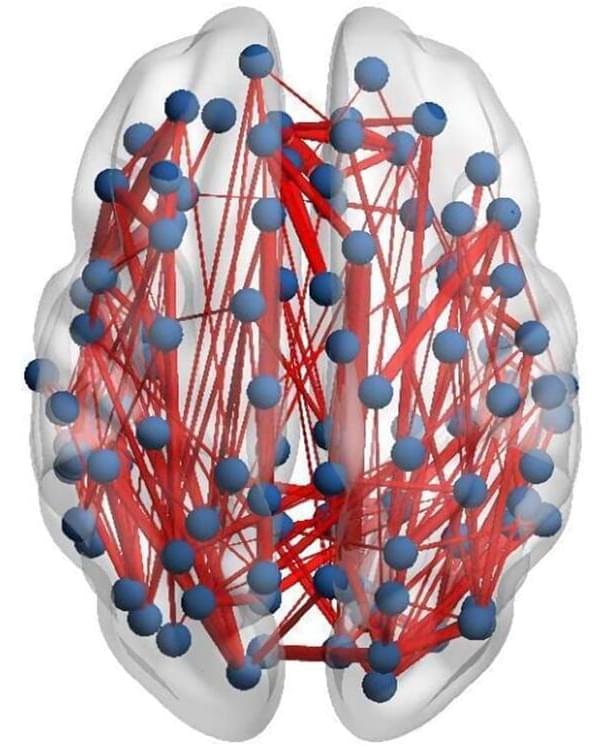

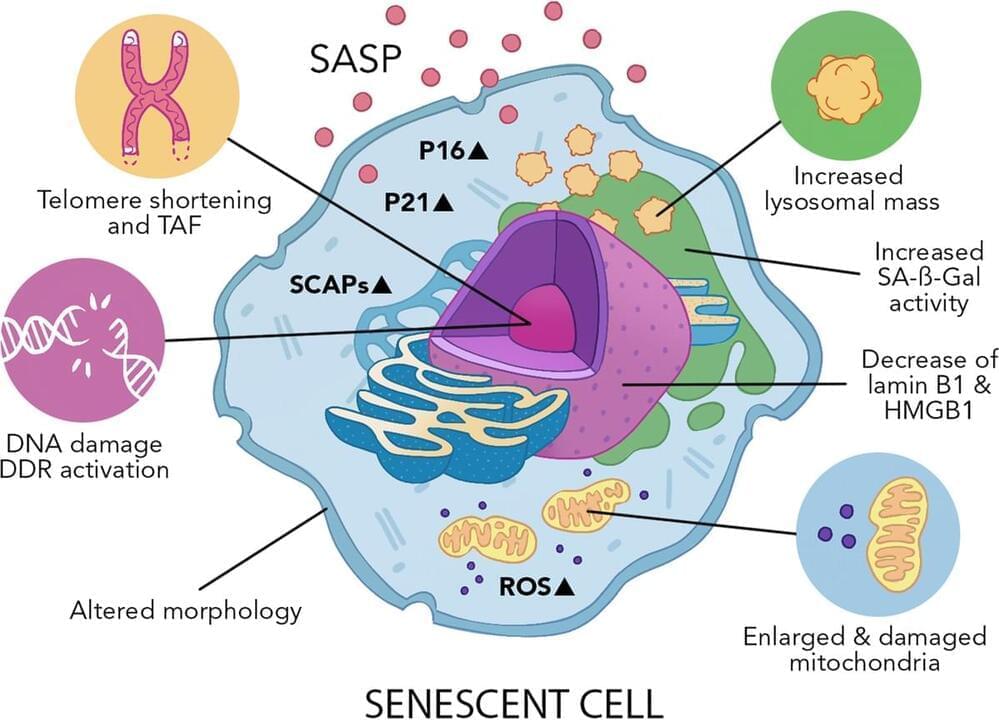

The research team reports in the journal Science Advances that early-life molecular processes of brain development are likely a major determinant of obesity risk. Previous large human studies have shown that the genes most strongly associated with obesity are expressed in the developing brain. This most recent study in mice focused on epigenetic development. Epigenetics is a molecular bookmarking system that regulates whether genes are utilized or not in certain cell types.

“Decades of research in humans and animal models have shown that environmental influences during critical periods of development have a major long-term impact on health and disease,” said corresponding author Dr. Robert Waterland, professor of pediatrics-nutrition and a member of the USDA Children’s Nutrition Research Center at Baylor. “Body weight regulation is very sensitive to such ‘developmental programming,’ but exactly how this works remains unknown.”