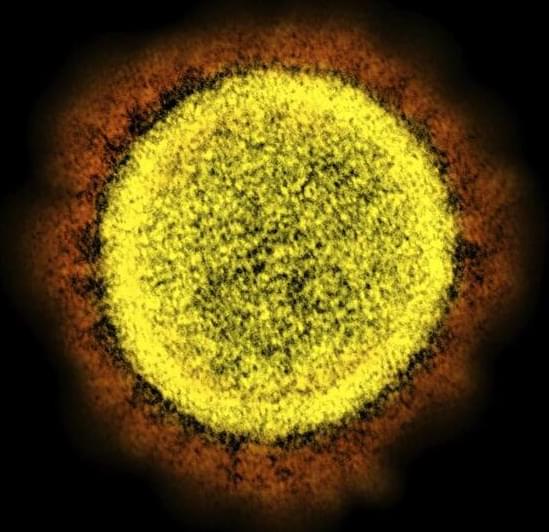

SARS-CoV-2 is evolving “rapidly,” spawning one new variant after another. But omicron continues to dominate, raising new questions about how evolution of the virus is headed.

Insider obtained documents that reveal the topics, goals and challenges discussed. Together, they show Amazon’s ambition to take on Google’s DeepMind, a pioneer in AI-powered scientific discovery. This could take Amazon from dabbling in healthcare services, and turn it into a potentially serious player in the future of medicine.

“The demarcation line between core Amazon/AWS business and life science and healthcare is shifting,” said Amazon scientist and senior solutions architect Sergey Menis, according to a transcript of his comments seen by Insider. “We are increasingly more specialized in healthcare and life sciences.” An Amazon spokesperson declined to comment.

Menis developed a nanoparticle that underpins a promising HIV vaccine candidate. He was joined at last week’s Amazon Machine Learning Conference by Amazon’s chief medical officer Taha Kass-Hout.

Circa 2009

Scientists have developed a revolutionary surgical treatment that could allow women with cancer to regrow their breasts after a mastectomy.

Human trials for the procedure, which scientists hope could replace breast reconstructions and implants, will start within three to six months, it was revealed in Melbourne, Australia. It is likely to be three years before the technique is fully developed, researchers said.

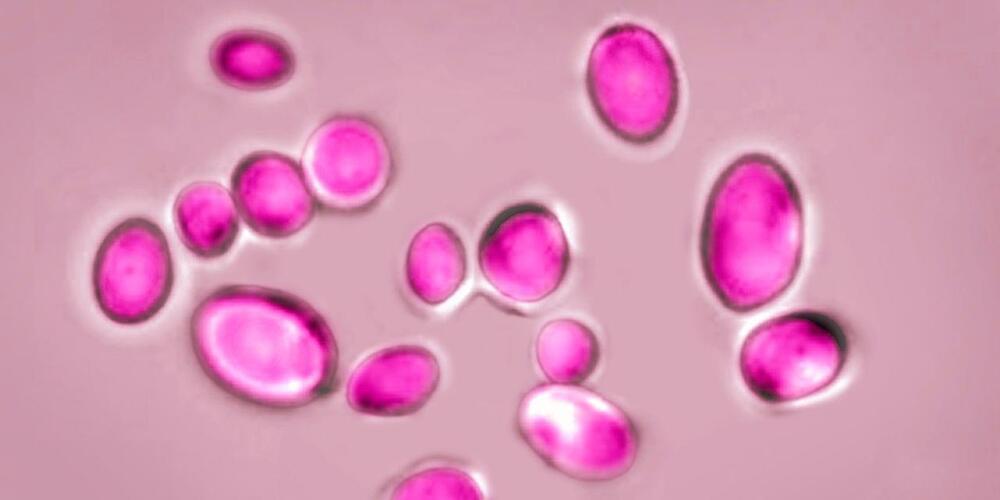

Fungi is getting stronger globally even alerting the WHO due to its damage.

The World Health Organization created a list of fungi that it said pose a growing risk to human health, including yeasts and molds found in abundance in nature and the body.

The WHO said Tuesday that the 19 species on the list merit urgent attention from public-health officials and drug developers. Four species were designated as threats of the highest priority: Aspergillus fumigatus, a mold found abundantly in nature; Candida albicans, which is commonly found in the human body; Candida auris, a highly deadly yeast; and Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus that can cause deadly brain infections.

“Fungal infections are growing, and are ever more resistant to treatments, becoming a public-health concern worldwide” said Hanan Balkhy, the WHO’s assistant director-general.

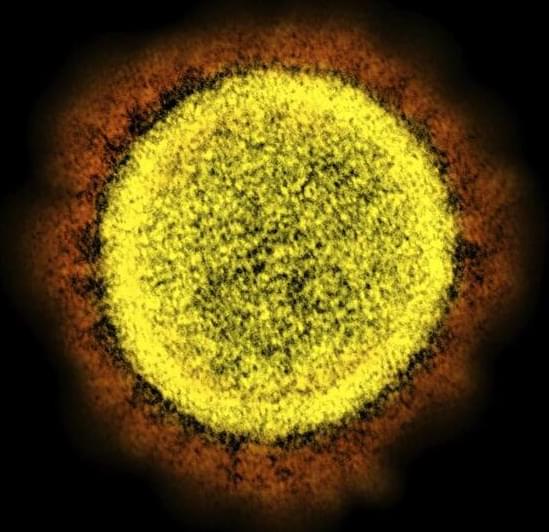

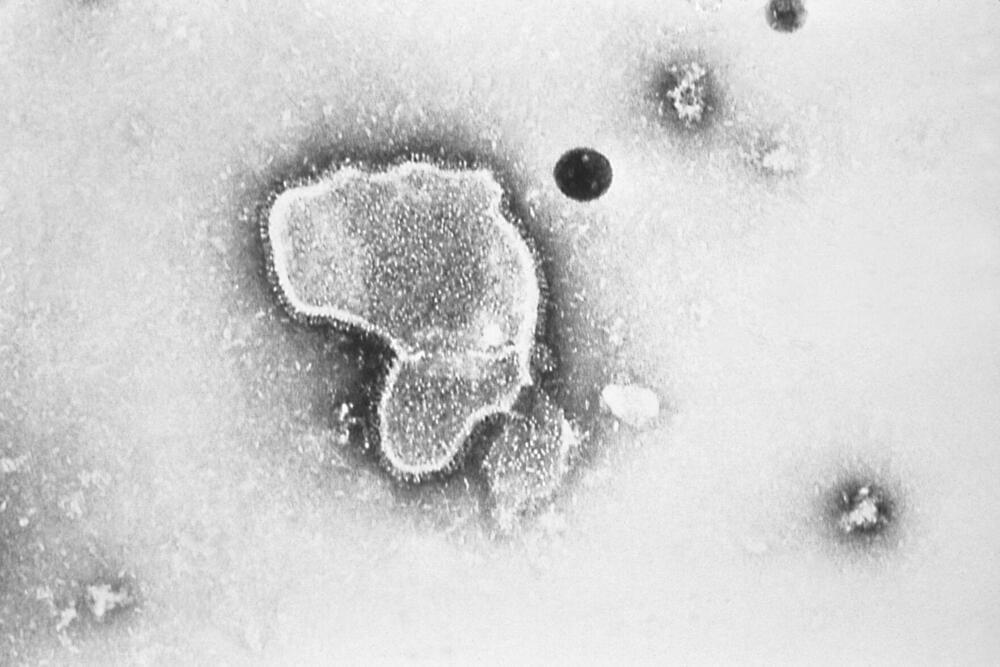

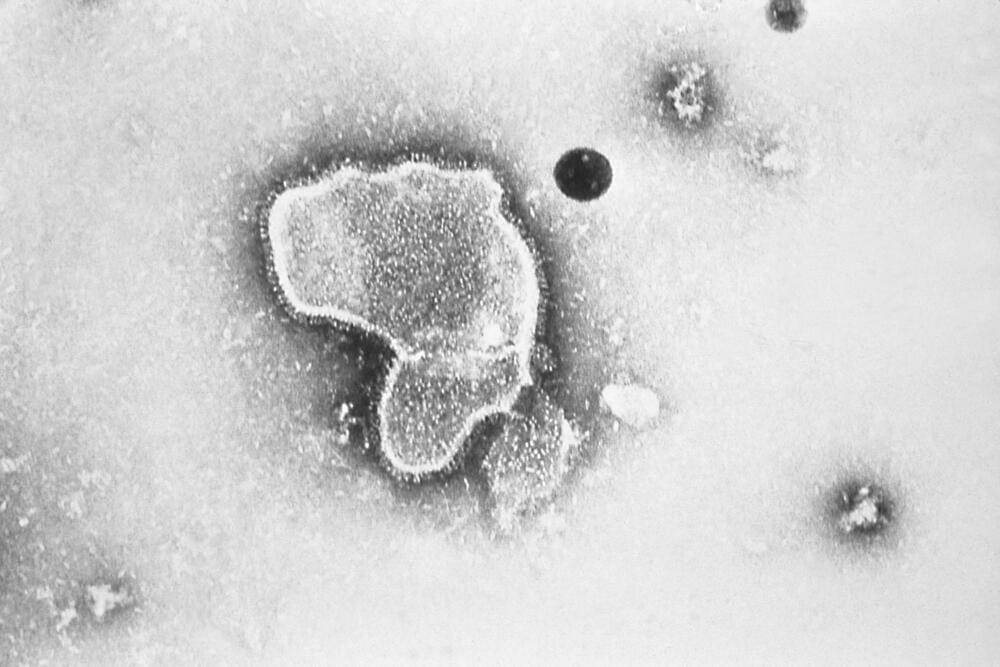

Research at Boston University that involved testing a lab-made hybrid version of the SARS-CoV-2 virus is garnering heated headlines alleging the scientists involved could have unleashed a new pathogen.

There is no evidence the work, performed under biosecurity level 3 precautions in BU’s National Emerging Infectious Diseases Laboratories, was conducted improperly or unsafely. In fact, it was approved by an internal biosafety review committee and Boston’s Public Health Commission, the university said Monday night.

But it has become apparent that the research team did not clear the work with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, which was one of the funders of the project. The agency indicated it is going to be looking for some answers as to why it first learned of the work through media reports.

An interdisciplinary team of researchers from Korea, Australia, Great Britain, and Germany—with participation of Leibniz Institute of Photonic Technology (Leibniz IPHT)—were able for the first time to optimize an optical glass fiber in such a way that light of different wavelengths can be focused extremely precisely. The level of accuracy is achieved by 3D nanoprinting of an optical lens applied to the end of the fiber.

This opens up new possibilities for applications in microscopy and endoscopy as well as in laser therapy and sensor technology. The researchers published their results in the journal Nature Communications.

Lenses at the end faces of optical fibers currently used in endoscopy for medical diagnostics have the disadvantage of chromatic aberration. This imaging error of optics, caused by the fact that light of different wavelengths, i.e., different spectral colors, is shaped and refracted differently, leads to a shift in the focal point and thus to blurring in imaging over a wide range of wavelengths. Achromatic lenses, which can minimize these optical aberrations, provide a remedy.

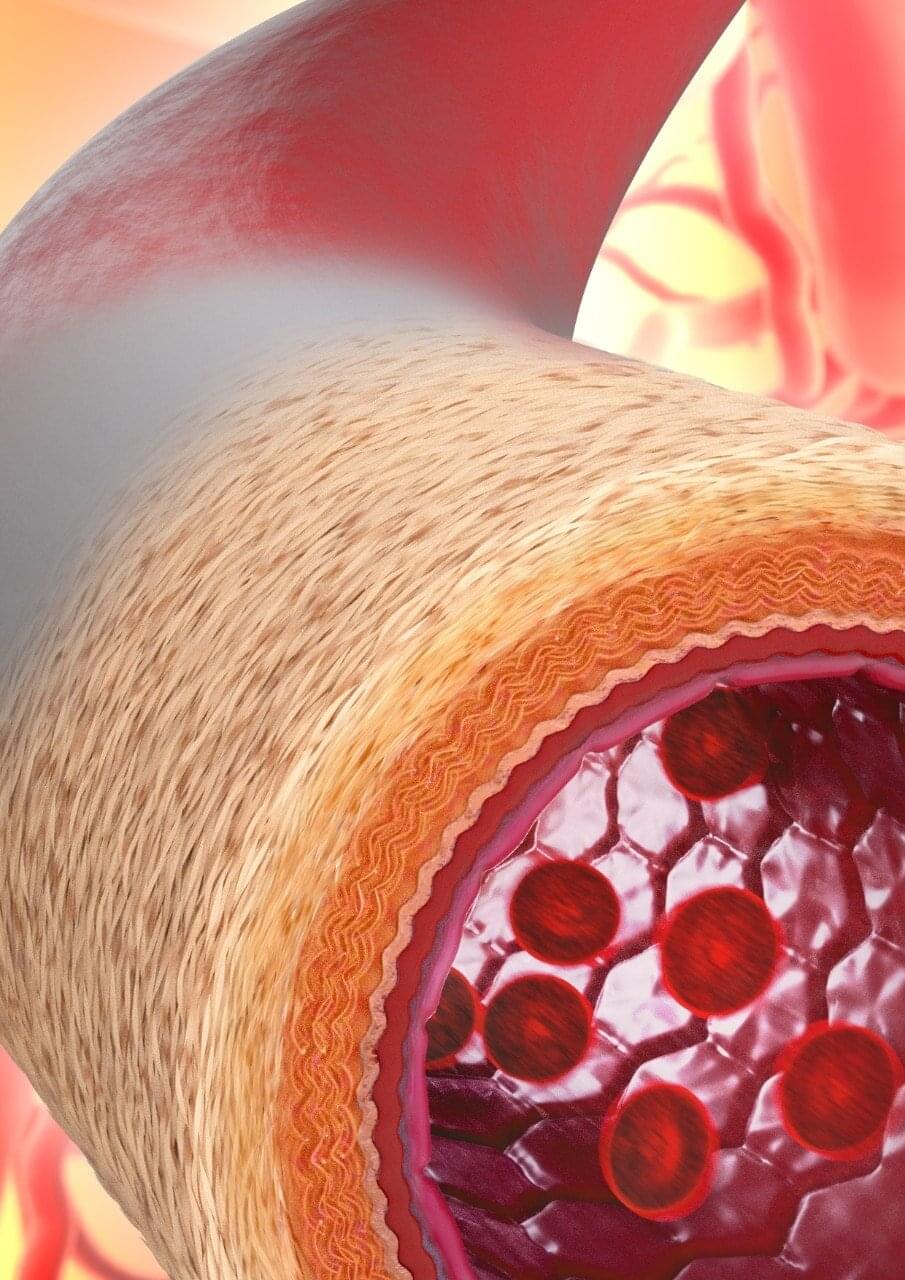

An international consortium of researchers led by the University of Sydney, has developed technology to enable the manufacturing of materials that mimic the structure of living blood vessels, with significant implications for the future of surgery.

Preclinical testing found that following transplantation of the manufactured blood vessel into mice, the body accepted the material, with new cells and tissue growing in the right places—in essence transforming it into a “living” blood vessel.

Senior author Professor Anthony Weiss from the Charles Perkins Center said while others have tried to build blood vessels with various degrees of success before, this is the first time scientists have seen the vessels develop with such a high degree of similarity to the complex structure of naturally occurring blood vessels.

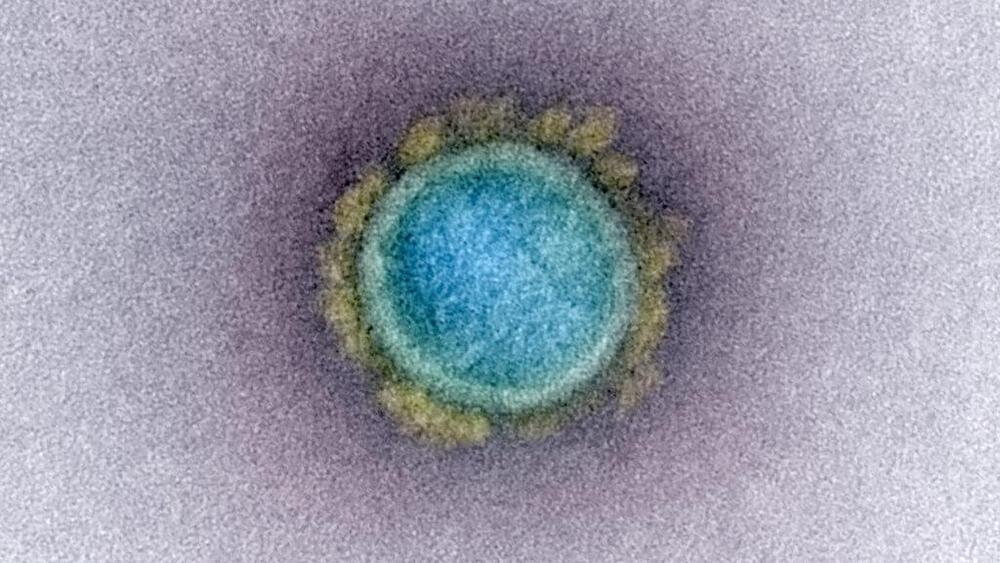

Children’s hospitals in parts of the U.S. are seeing a surge in a common respiratory illness that can cause severe breathing problems for babies.

RSV cases fell dramatically two years ago as the pandemic shut down schools, day cares and businesses. With restrictions easing in the summer of 2021, doctors saw an alarming increase in what is normally a fall and winter virus.

Now, it’s back again. And doctors are bracing for the possibility that RSV, flu and COVID-19 could combine to stress hospitals.

An international team of scientists has found toothed fish remains that date back 439 million years, which suggests that the ancestors of modern chondrichthyans (sharks and rays) and osteichthyans (ray-and lobe-finned fish) originated far earlier than previously believed.

The findings were recently published in the prestigious journal Nature.

A remote location in south China’s Guizhou Province has yielded magnificent fossil findings, including solitary teeth identified as belonging to a new species (Qianodus duplicis) of primitive jawed vertebrate from the ancient Silurian period (about 445 to 420 million years ago). Qianodus, named after the ancient name for the present-day Guizhou, possessed unusual spiral-like dental elements carrying several generations of teeth that were inserted throughout the course of the animal’s life.