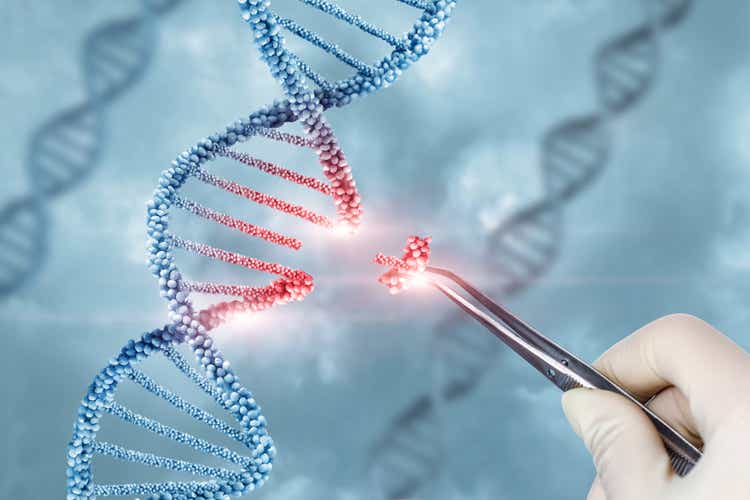

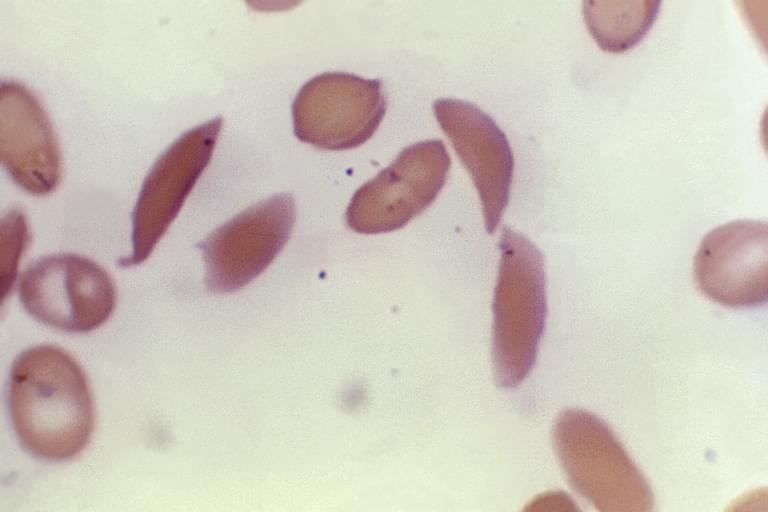

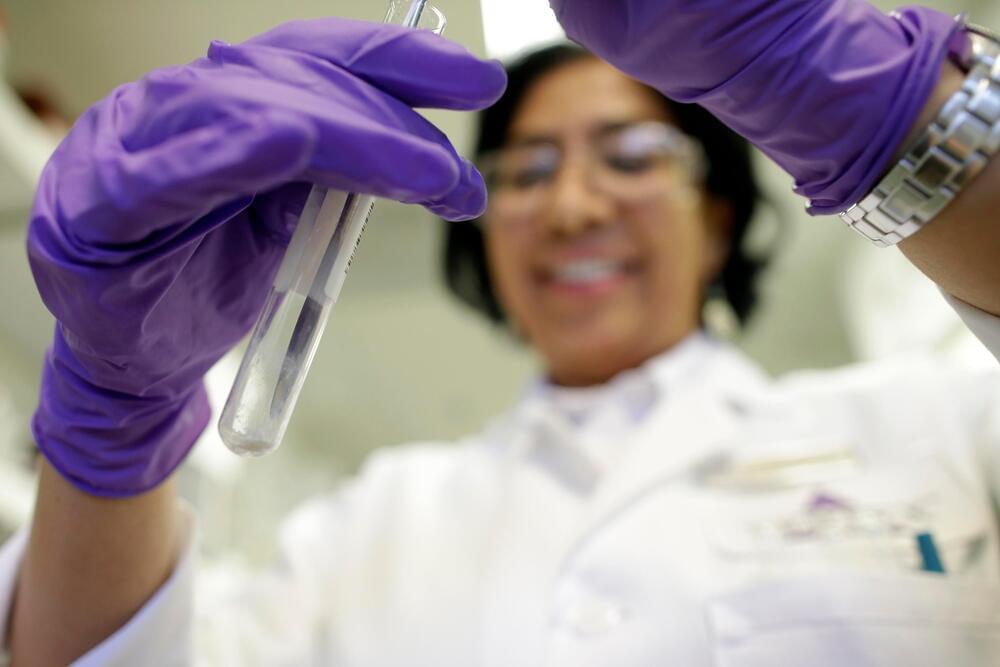

Advancements in genetic engineering, gene therapies, and anti-aging research may eventually allow for age reversal and the restoration of youthful health and longevity.

What is the key idea of the video?

—The key idea is that advancements in genetic engineering and anti-aging research may eventually allow for age reversal and the restoration of youthful health and longevity.

How can aging be reversed?

—Aging can be reversed through rejuvenating the brain, restoring memories and learning abilities, and addressing the loss of inherited information through genetic engineering and epigenetic reprogramming.