Gene editing is revolutionizing the understanding of health and disease, providing researchers with vast opportunities to advance the development of novel treatment approaches. Traditionally, researchers used various methods to introduce double strand breaks (DSBs) into the genome, including transactivator-like effectors, meganucleases, and zinc finger nucleases. While useful, these techniques are limited in that they are time and labor intensive, less efficient, and can have unintended effects. In contrast, the clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeat (CRISPR)-associated protein-9 (Cas9) system (CRISPR/Cas9) is among the most sensitive and efficient methods for creating DNA DSBs, making it the leading gene editing technology.

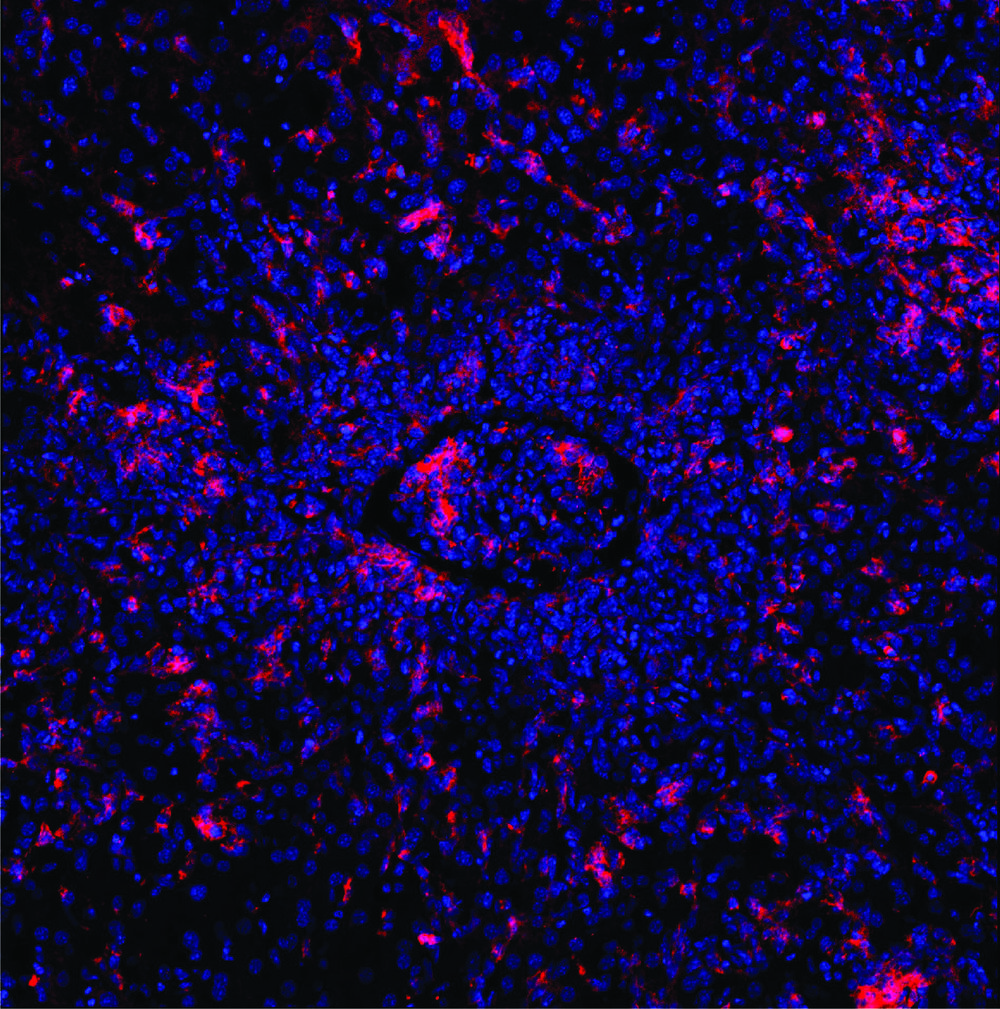

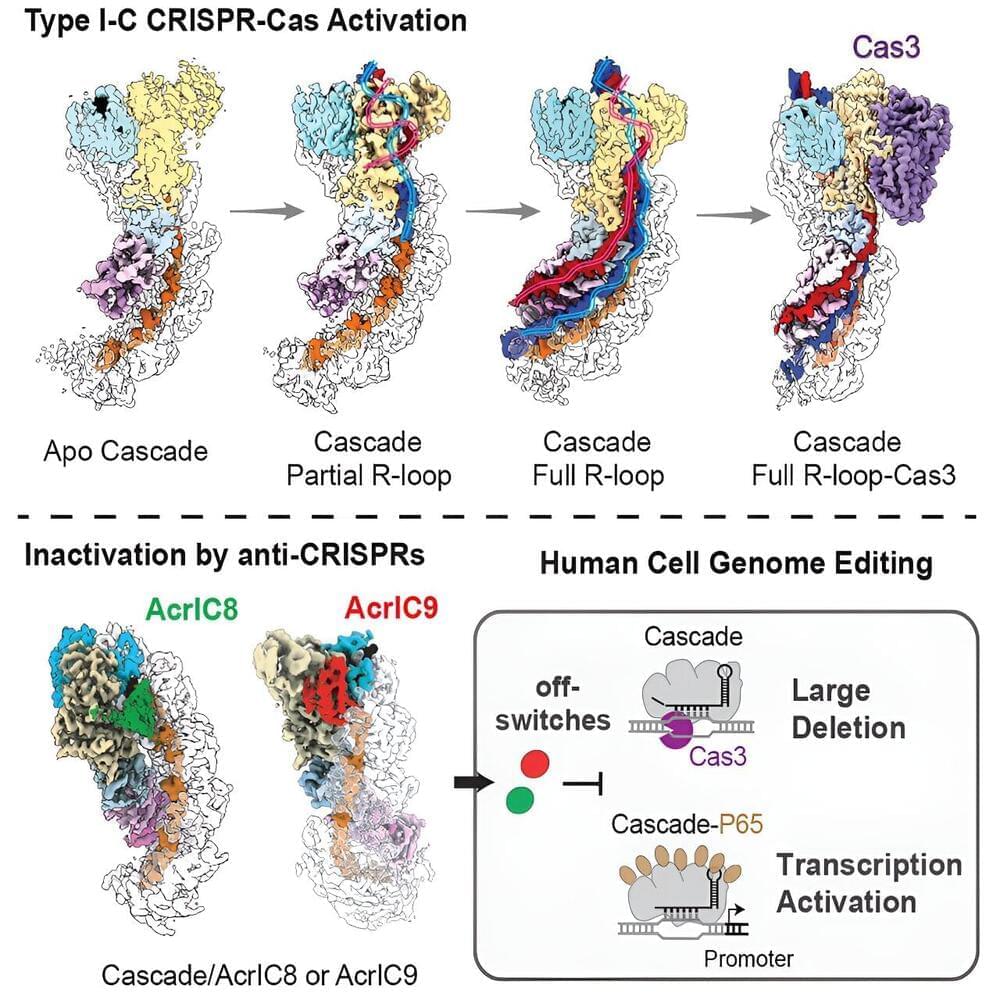

CRISPR/Cas9 is a naturally occurring immune protective process that bacteria use to destroy foreign genetic material.1 Researchers repurposed the CRISPR/Cas9 system for genetic engineering applications in mammalian cells, exploiting the molecular processes that introduce DSBs in specific sections of DNA, which are then repaired to turn certain genes on or off, or to correct genomic errors with extraordinary precision.2,3 This technology’s applications are far reaching, from cell culture and animal models to translational research that focuses on correcting genetic mutations in diseases such as cancer, hemophilia, and sickle cell disease.4

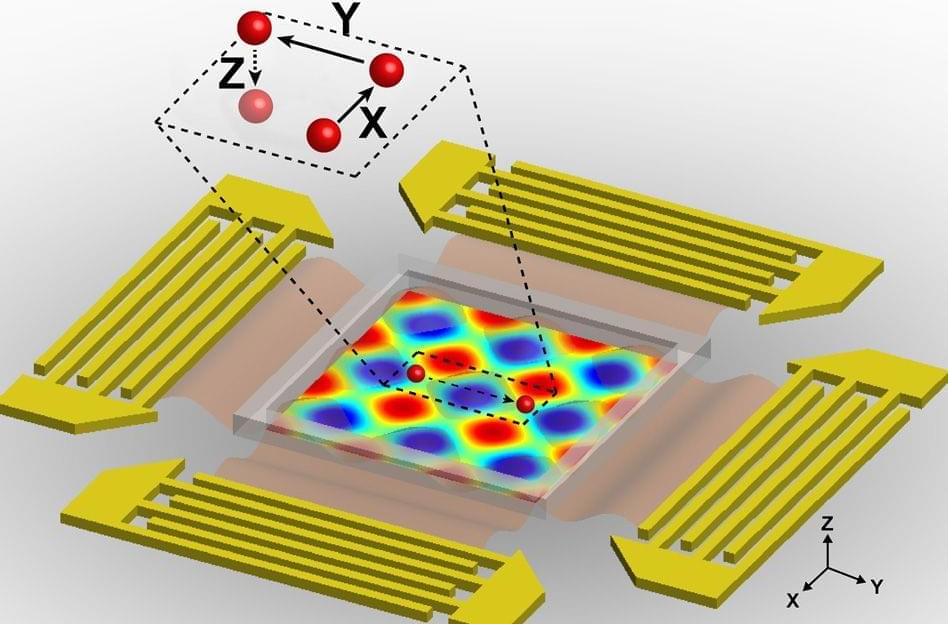

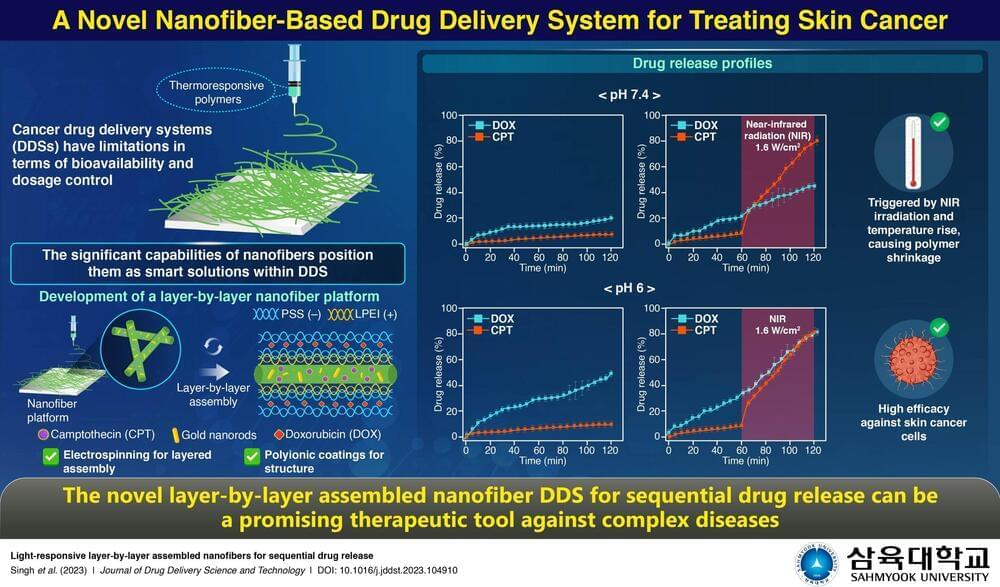

Researchers exploit plasmids, the small, closed circular DNA strands native to bacteria, as delivery vehicles in CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing protocols. Plasmids shuttle the CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing components to target cells and can be manipulated to control gene editing activity, including targeting multiple genes at a time. Plasmids can also deliver gene repair instructions and machinery. For example, poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase 1 (PARP1) is an enzyme that drives DNA repair and transcription.5 It is a critical aspect of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology in part because it helps repair the DSBs created by the CRISPR/Cas9 system. PARP1 CRISPR plasmids can edit, knockout, or upregulate PARP1 gene expression depending on the specific instructions encoded in the plasmid.