𝐌𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐗𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬:

The Neuro-Network.

𝐑𝐞𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐜𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐨𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐜𝐞𝐥𝐥𝐬 𝐚 𝐠𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐭𝐢𝐜 𝐦𝐮𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐭𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐠𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐬𝐭 𝐀𝐥𝐳𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐦𝐞𝐫’𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞

𝙍𝙚𝙨𝙚𝙖𝙧𝙘𝙝𝙚𝙧𝙨 𝙛𝙧𝙤𝙢 𝙩𝙝𝙚 𝙐𝙣𝙞𝙫𝙚𝙧𝙨𝙞𝙩𝙚́ 𝙇𝙖𝙫𝙖𝙡 𝙁𝙖𝙘𝙪𝙡𝙩𝙮 𝙤𝙛 𝙈𝙚𝙙𝙞𝙘𝙞𝙣𝙚 𝙖… See more.

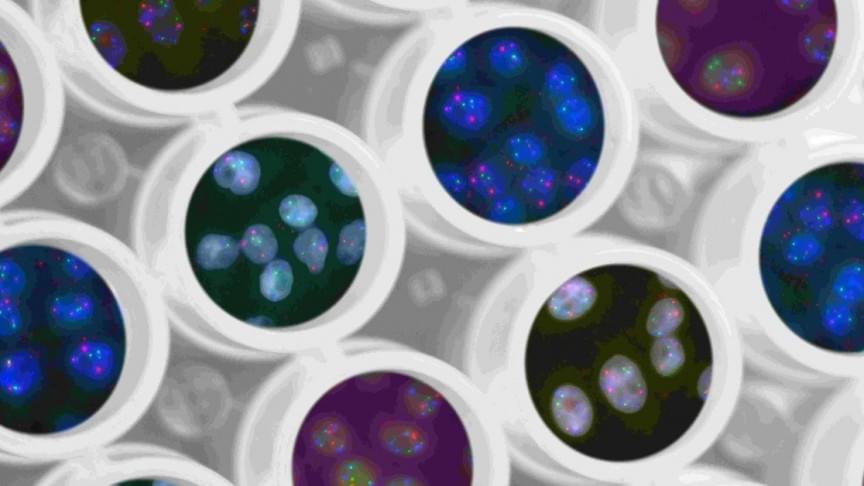

Researchers from the Université Laval Faculty of Medicine and CHU de Québec–Université Laval Research Center have successfully edited the genome of human cells grown in vitro to introduce a mutation providing protection against Alzheimer’s disease. The details of this breakthrough were recently published in The CRISPR Journal.

“Some genetic mutations increase the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease, but there is a mutation that reduces this risk,” says lead author Professor Jacques-P. Tremblay. “This is a rare mutation identified in 2012 in the Icelandic population. The mutation has no known disadvantage for those who carry it and reduces the risk of developing Alzheimer’s disease. Using an improved version of the CRISPR gene editing tool, we have been able to edit the genome of human cells to insert this mutation.”