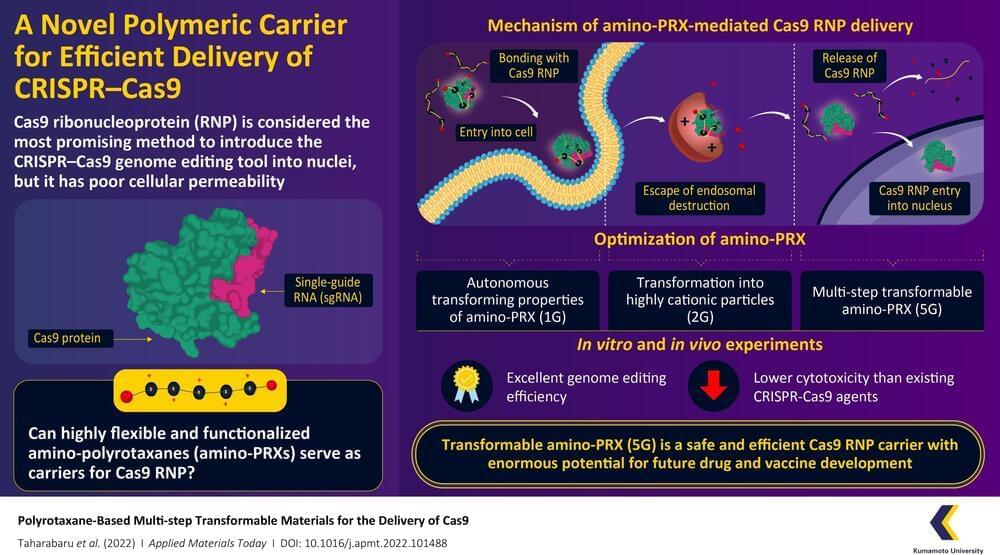

CRISPR-Cas9 is considered a revolutionary gene editing tool, but its applications are limited by a lack of methods by which it can be safely and efficiently delivered into cells. Recently, a research team from Kumamoto University, Japan, have constructed a highly flexible CRISPR-Cas9 carrier using aminated polyrotaxane (PRX) that can not only bind with the unusual structure of Cas9 and carry it into cells, but can also protect it from intracellular degradation by endosomes.

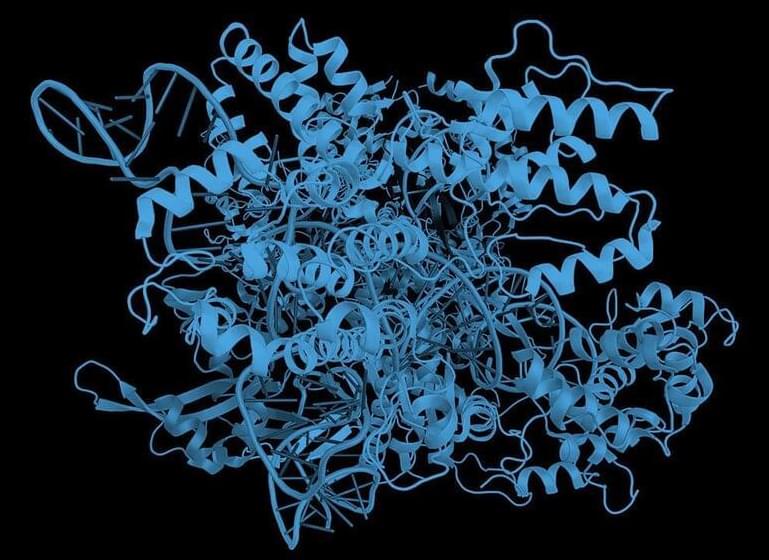

Clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats (CRISPR) and their accompanying protein, CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9), made international headlines a few years ago as a game-changing genome editing system. Consisting of Cas9 and strand of genetic material known as a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), the system can target specific regions of DNA and function as “molecular scissors” to make precise edits. The direct delivery of Cas9–sgRNA complexes, i.e. Cas9 ribonucleoproteins (RNPs), into the nucleus of the cell is considered the safest and most efficient way to achieve genome editing. However, the Cas9 RNP has poor cellular permeability, and thus requires a carrier molecule to transport it past the first hurdle of the cell membrane before it can get to the cell nucleus. These carriers need to bind with Cas9 RNP, carry it into the cell, prevent its degradation by intracellular organelles called “endosomes,” and finally release it without causing any changes to its structure.

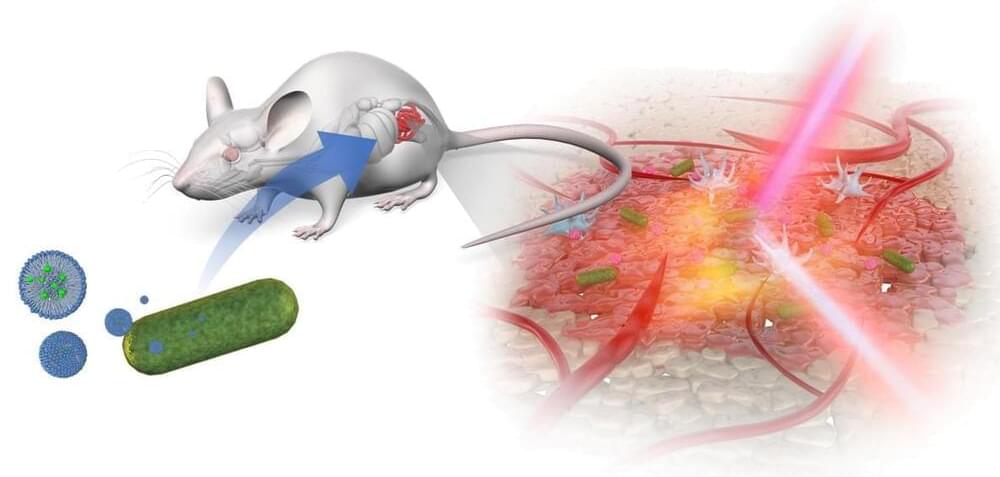

In a recent paper published in the June 2022, Volume 27 of Applied Materials Today, a research team from Kumamoto University has developed a transformable polyrotaxane (PRX) carrier that can facilitate genome editing using Cas9RNP with high efficiency and usability. “While there have been some PRX-based drug carriers for nucleic acids and proteins reported before, this is the first report on PRX-based Cas9 RNP carrier. Moreover, our findings describe how to precisely control intracellular dynamics across multiple steps. This will prove invaluable for future research in this direction,” says Professor Keiichi Motoyama, a corresponding author of the paper.