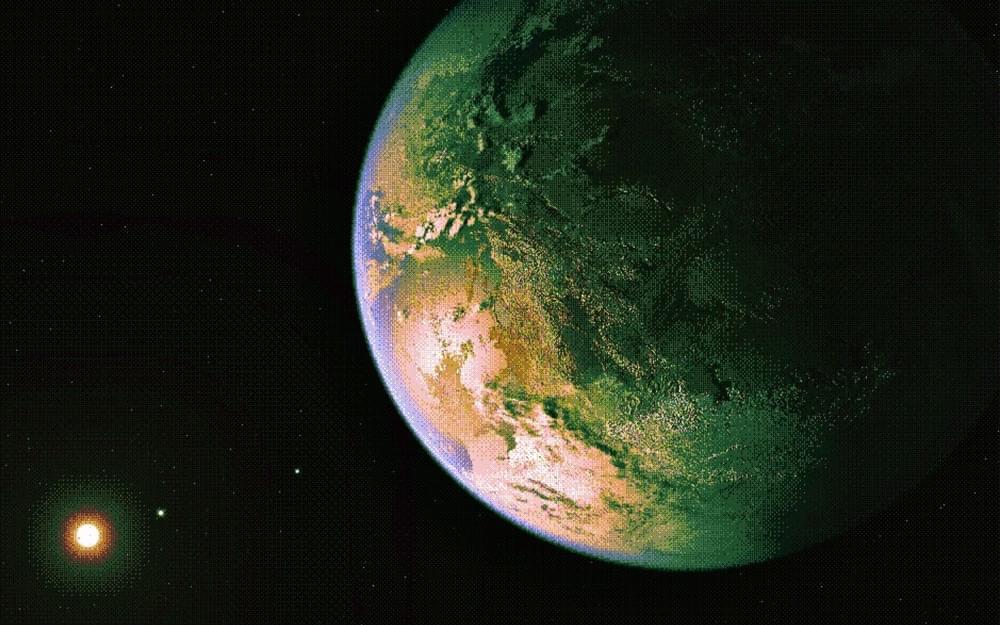

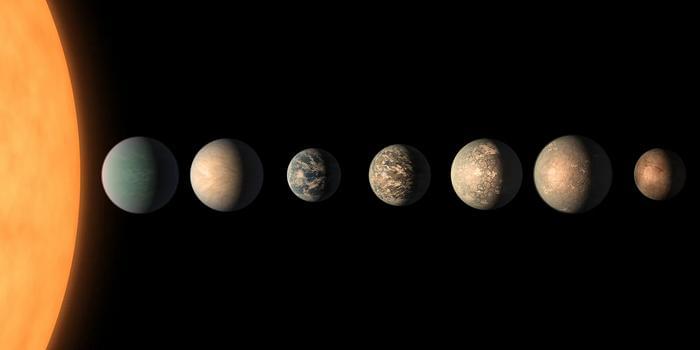

According to astrophysicist Erik Zackrisson’s computer model, there could be about 70 quintillion planets in the universe. However, most of these planets are vastly different from Earth — they tend to be larger, older, and not suited for life. Only around 63 exoplanets have been found in their stars’ habitable zones, making Earth potentially one of the few life-sustaining planets. This could explain Fermi’s paradox — the puzzling lack of evidence for extraterrestrial life. While we continue searching, Earth might be truly special.

After reading the article, Harry gained more than 55 upvotes with this comment: “If life developing on Earth the way it has is 1 in a billion, then this would imply that there is life on at least a billion other planets (?)”

The prevailing belief among astronomers is that the number of planets should at least match the number of stars. With 100 billion galaxies in the universe, each containing about a billion trillion stars, there should be an equally vast number of exoplanets, including Earth-like worlds — in theory.