If you’re interested in superlongevity and superintelligence, then I have a book to recommend., by Sonia Contera, is a book about the intersection of biotech and nanotech. Interesting and well written for the layman, the book covers some of the latest developments in nanotechnology as it applies to biological matters. Although there are many topics, I was primarily interested in the DNA nanobots, DNA origami, and the protein nanotechnology sections. My interest is piqued in these arenas due to my expectation that DNA nanobots and protein nanobots, as well as complex self-assembled custom nanostructures, are going to be key to some of the longevity technologies and some of the possible substrates for mind uploading that are key to superlongevity and superintelligence. There are also sections in the book on 3D bioprinted organs — progress and possibilities, as well as difficulties.

There is even a section that clearly was written specifically to address a discussion that has engaged my friends, Dinorah Delfin and Dan Faggella. The title is:

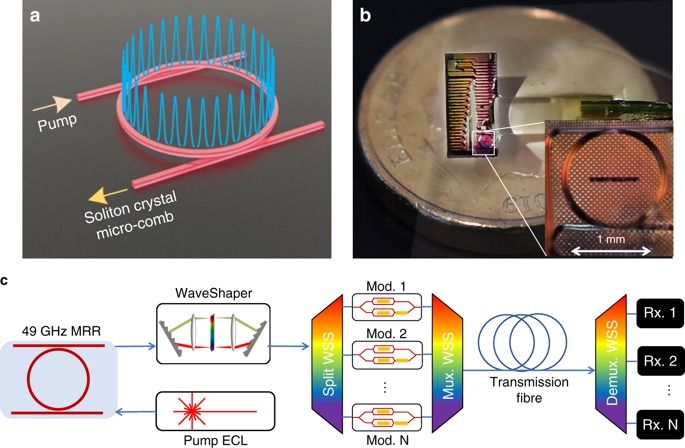

FUTURE DEVICES: QUANTUM PHYSICS MEETS BIOLOGY MEETS NANOTECHNOLOGY

Now, some might be tempted to consider that particular combination to be “woo woo”, however, please keep in mind the author’s credentials. Sonia Contera is a professor of biological physics in the Department of Physics at the University of Oxford.

Increasingly, scientists are gaining control over matter at the nanometer scale. Spearheaded by physical scientists operating at the interfaces of physics and biology, advances in nanoscience and technology are transforming how people think about life and treat human health.