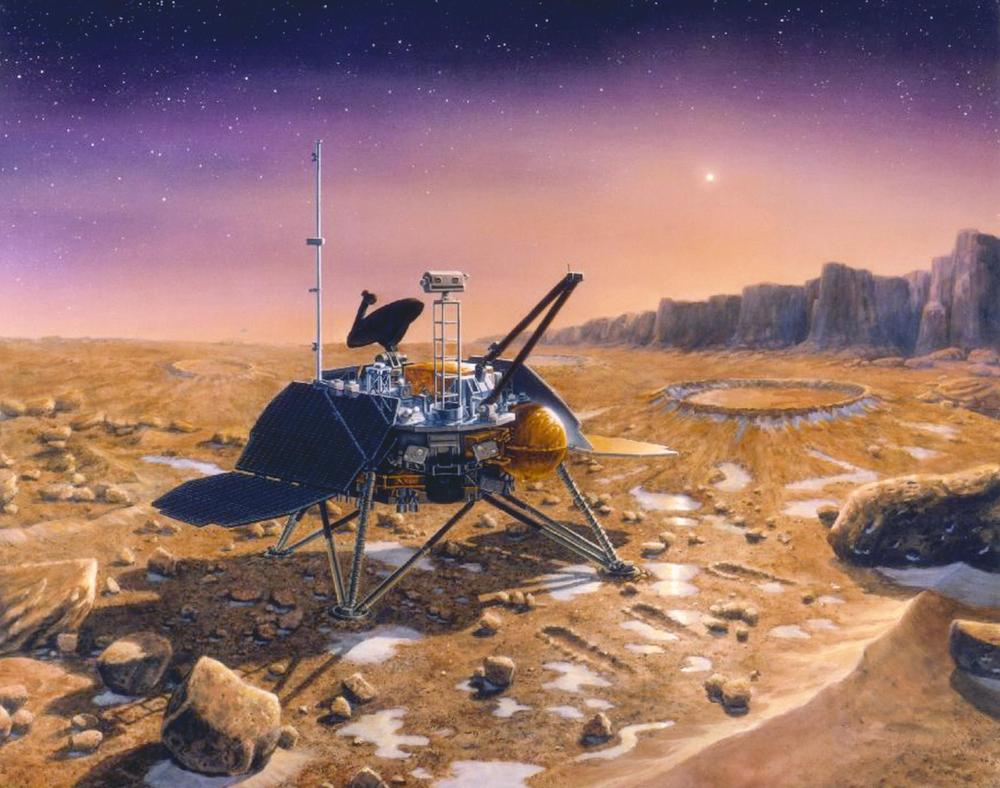

No, dear Pope Francis. I 100% share the concept of the brotherhood of all humans. There can never be too many calls for brotherhood. What I do not share in the most absolute way is that it is “useless to go to the Moon, if we are not brothers on Earth”. Quite opposite: eight billion humans, closed on the surface of our mother planet, will not be able to be brothers unless they will achieve new resources, new spaces, a new horizon of development. Remaining confined to the ground we would find ourselves competing in a zero sum game, or worse, an increasingly negative sum game, considering how much the resources of planet Earth, especially the environmental ones, are already scarce. Once again, it is up to people of good will to refuse to remain and fight among brothers and sisters, and to resume the courageous path of exploration, the search for new resources, the opening of new frontiers and human settlement in space. Properly in order to nourish the many brothers and sisters in peace, harmony and freedom. Otherwise mafias, tyrannies, selfishness, fratricide and infanticide will prevail, as history unfortunately testifies, every time a world has become small and suffocating. Pandemics such as covid19 also teach us that we will be more and more forced into immobility in our homes, if we will insist on remaining in increasing numbers in a philosophically and physically closed world. Let alone “grow and multiply”. Now, from a Jesuit Pope I would have expected at least that he would not run into the most obvious clichés, like “before going into space we must solve problems on Earth”. Quite the contrary: if we will not urgently kick-off the civil expansion into space, not only will we not be able to solve Earth’s problems, but they will get worse and worse, bringing civilization to a very dangerous point of no return.

The Feast of the Assumption of Mary into Heaven coincides with August 15th. Bergoglio remembers those who do not have the opportunity to celebrate. And on the issue of the Nile between Egypt, Ethiopia and Sudan he calls for dialogue and brotherhood.