With SpaceX aiming to send the first humans to Mars in 2024, they will need to set up the essentials like water and power before they get there.

Working in conjunction with Singapore’s Agency for Science, Technology and Research, Insectta’s technology uses a proprietary and environmentally friendly process to extract lucrative substances such as chitosan, melanin and probiotics from the larvae, it said.

SINGAPORE (Reuters) — In a quiet, mainly residential district of Singapore, trays of writhing black soldier fly larvae munch their way through hundreds of kilograms of food waste a day.

The protein-rich maggots can be sold for pet food or fertiliser, but at Insectta — a startup that says it is Singapore’s first urban insect farm — they are bred to extract biomaterials that can be used in pharmaceuticals and electronics.

“What these black soldier flies enable us to do is transform this food waste, which is a negative-value product, into a positive-value product,” said Chua Kai-Ning, Insectta’s co-founder and chief marketing officer.

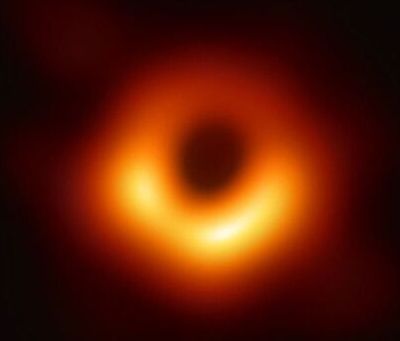

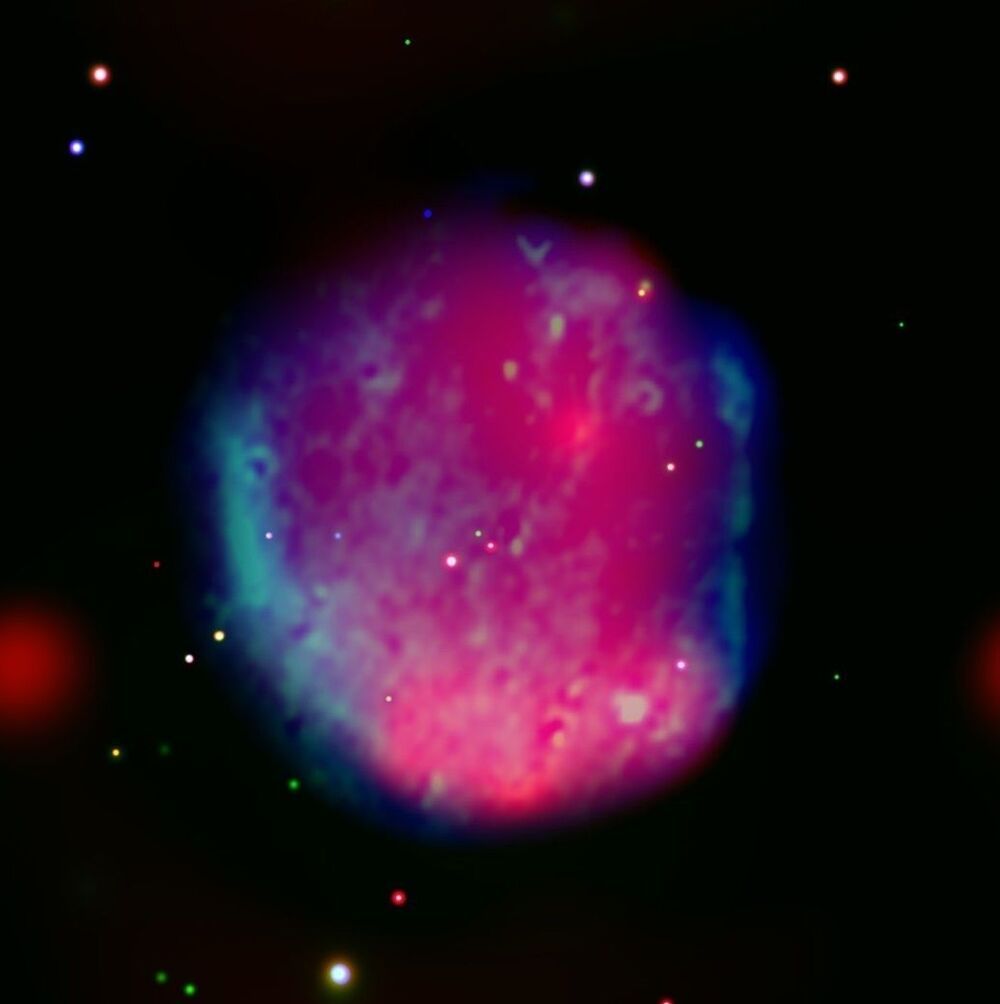

Our sky is missing supernovas. Stars live for millions or billions of years. But given the sheer number of stars in the Milky Way, we should still expect these cataclysmic stellar deaths every 30–50 years. Few of those explosions will be within naked-eye-range of Earth. Nova is from the Latin meaning “new”. Over the last 2000 years, humans have seen about seven “new” stars appear in the sky – some bright enough to be seen during the day – until they faded after the initial explosion. While we haven’t seen a new star appear in the sky for over 400 years, we can see the aftermath with telescopes – supernova remnants (SNRs) – the hot expanding gases of stellar explosions. SNRs are visible up to a 150000 years before fading into the Galaxy. So, doing the math, there should be about 1200 visible SNRs in our sky but we’ve only managed to find about 300. That was until “Hoinga” was recently discovered. Named after the hometown of first author Scientist Werner Becker, whose research team found the SNR using the eROSITA All-Sky X-ray survey, Hoinga is one of the largest SNRs ever seen.

Hoinga is big. Really big. The SNR spans 4 degrees of the sky – eight times wider than the Full Moon. The obvious question – how could astronomers not have already found something THAT enormous? Hoinga is not where we typically are looking for supernova. Most of our SNR searches are focused on the plane of the Galaxy toward the Milky Way’s core where we’d expect to find the densest concentration of older and exploded stars. But Hoinga was found at high latitudes off the plane of the Galaxy.

Furthermore, Hoinga hides in the sky because it’s so large. At this scale, the SNR is difficult to distinguish from other large structures of dust and gas that make up the Galaxy known as the “Galactic Cirrus.” It’s like trying to see an individual cloud in an overcast sky. The Galactic Cirrus also outshines Hoinga in radio light, often used to search for SNRs, forcing Hoinga to hide in the background. Cross referencing with older radio sky surveys, the research team determined Hoinga had been observed before but was never identified as an SNR due to its comparatively faint glow in radio. Here eROSITA has an advantage as it sees X-rays. Hoinga shines brighter in X-ray light than the Galactic Cirrus allowing it to stand out from the Galaxy to be discovered.

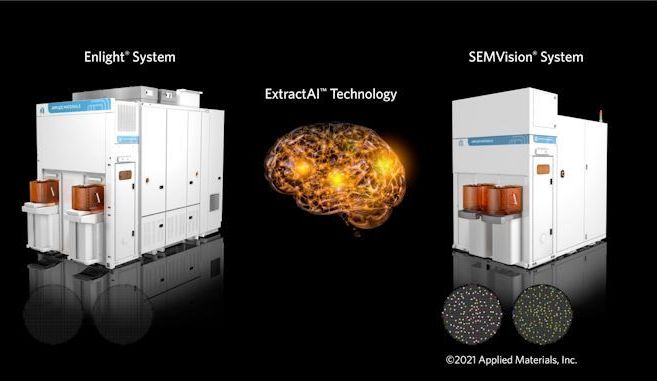

Advanced system-on-chip designs are extremely complex in terms of transistor count and are hard to build using the latest fabrication processes. In a bid to make production of next-generation chips economically feasible, chip fabs need to ensure high yields early in their lifecycle by quickly finding and correcting defects.

But finding and fixing defects is not easy today, as traditional optical inspection tools don’t offer sufficiently detailed image resolution, while high-resolution e-beam and multibeam inspection tools are relatively slow. Looking to bridge the gap on inspection costs and time, Applied Materials has been developing a technology called ExtractAI technology, which uses a combination of the company’s latest Enlight optical inspection tool, SEMVision G7 e-beam review system, and deep learning (AI) to quickly find flaws. And surprisingly, this solution has been in use for about a year now.

“Applied’s new playbook for process control combines Big Data and AI to deliver an intelligent and adaptive solution that accelerates our customers’ time to maximum yield,” said Keith Wells, group vice president and general manager, Imaging and Process Control at Applied Materials. “By combining our best-in-class optical inspection and eBeam review technologies, we have created the industry’s only solution with the intelligence to not only detect and classify yield-critical defects but also learn and adapt to process changes in real-time. This unique capability enables chipmakers to ramp new process nodes faster and maintain high capture rates of yield-critical defects over the lifetime of the process.”

Summary: A new genetic engineering strategy significantly reduces levels of tau in animal models of Alzheimer’s disease. The treatment, which involves a single injection, appears to have long-last effects.

Source: Mass General.

Researchers have used a genetic engineering strategy to dramatically reduce levels of tau–a key protein that accumulates and becomes tangled in the brain during the development of Alzheimer’s disease–in an animal model of the condition.

Layers of ice and rock obviate the need for “habitable zone” and shield life against threats.

SwRI researcher theorizes worlds with underground oceans may be more conducive to life than worlds with surface oceans like Earth.

One of the most profound discoveries in planetary science over the past 25 years is that worlds with oceans beneath layers of rock and ice are common in our solar system. Such worlds include the icy satellites of the giant planets, like Europa, Titan, and Enceladus, and distant planets like Pluto.

Urban Air Port has chosen to build its first Air-One transport hub for autonomous delivery drones and electric flying cars next to the Ricoh Arena in Coventry, UK. The futuristic facility will launch later this year. It will support delivery drone and air taxi technology and eventually transport cargo and people across cities.