Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Rapamycin Anti Aging — Worth The Hype?

Rapamycin is the drug used to suppress the immune system after organ transplants, but in reduced doses, it appears it may have other health benefits and as such is discussed considerably in the longevity community, and taken regularly my some very famous proponents.

So I thought I would give you some background, alongside the pros and cons, to see what all the fuss is about…

Rapamycin Anti Aging.

Rapamycin is very popular in the anti aging paradigm so let’s have a look at what it is, what it offers, and what the trade offs are… because, well, it is always wise to have all the data.

If you want to know more about the hallmarks of aging I mentioned then check this out.

Japanese sea slugs regrow new hearts and bodies | Regeneration | Decapitation | English World News

Researchers have discovered that two species of Japanese sea slugs can regrow hearts and whole new bodies even after removing their own heads.

#JapaneseSeaSlugs #RegrowHearts #RegrowBodies.

About Channel:

WION-The World is One News, examines global issues with in-depth analysis. We provide much more than the news of the day. Our aim to empower people to explore their world. With our Global headquarters in New Delhi, we bring you news on the hour, by the hour. We deliver information that is not biased. We are journalists who are neutral to the core and non-partisan when it comes to the politics of the world. People are tired of biased reportage and we stand for a globalised united world. So for us the World is truly One.

Please keep discussions on this channel clean and respectful and refrain from using racist or sexist slurs as well as personal insults.

Check out our website: http://www.wionews.com.

Neural network CLIP mirrors human brain neurons in image recognition

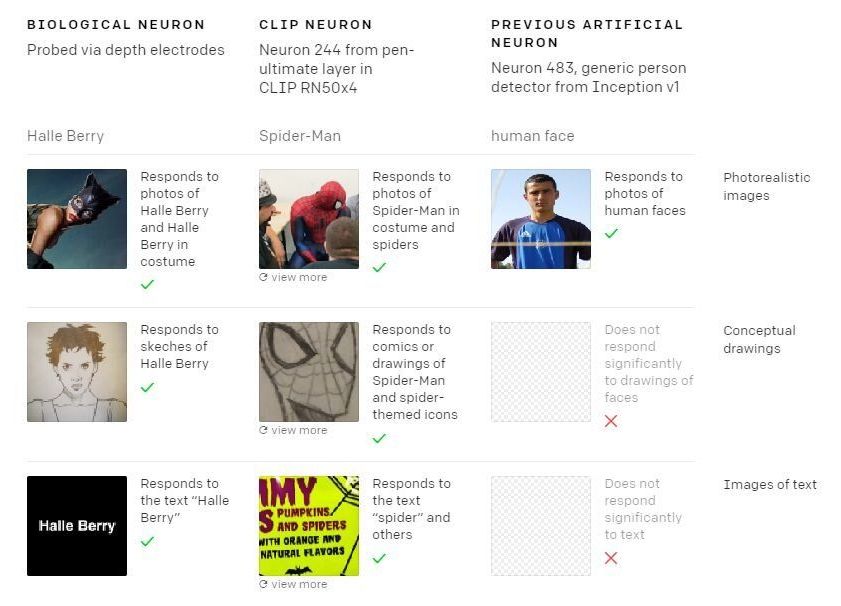

Open AI, the research company founded by Elon Musk, has just discovered that their artificial neural network CLIP shows behavior strikingly similar to a human brain. This find has scientists hopeful for the future of AI networks’ ability to identify images in a symbolic, conceptual and literal capacity.

While the human brain processes visual imagery by correlating a series of abstract concepts to an overarching theme, the first biological neuron recorded to operate in a similar fashion was the “Halle Berry” neuron. This neuron proved capable of recognizing photographs and sketches of the actress and connecting those images with the name “Halle Berry.”

Now, OpenAI’s multimodal vision system continues to outperform existing systems, namely with traits such as the “Spider-Man” neuron, an artificial neuron which can identify not only the image of the text “spider” but also the comic book character in both illustrated and live action form. This ability to recognize a single concept represented in various contexts demonstrates CLIP’s abstraction capabilities. Similar to a human brain, the capacity for abstraction allows a vision system to tie a series of images and text to a central theme.

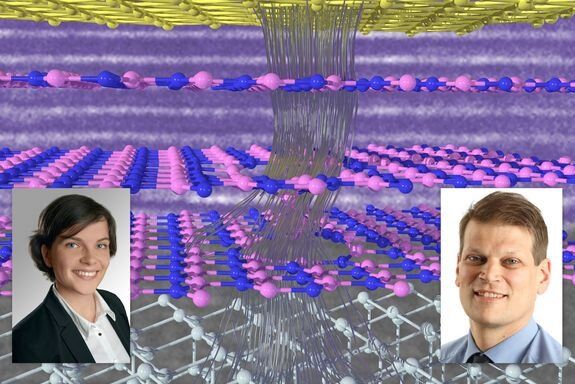

Microchips of the future: Suitable insulators are still missing

For decades, there has been a trend in microelectronics towards ever smaller and more compact transistors. 2D materials such as graphene are seen as a beacon of hope here: they are the thinnest material layers that can possibly exist, consisting of only one or a few atomic layers. Nevertheless, they can conduct electrical currents—conventional silicon technology, on the other hand, no longer works properly if the layers become too thin.

However, such materials are not used in a vacuum; they have to be combined with suitable insulators—in order to seal them off from unwanted environmental influences, and also in order to control the flow of current via the so-called field effect. Until now, hexagonal boron nitride (hBN) has frequently been used for this purpose as it forms an excellent environment for 2D materials. However, studies conducted by TU Wien, in cooperation with ETH Zurich, the Russian Ioffe Institute and researchers from Saudi Arabia and Japan, now show that, contrary to previous assumptions, thin hBN layers are not suitable as insulators for future miniaturized field-effect transistors, as exorbitant leakage currents occur. So if 2D materials are really to revolutionize the semiconductor industry, one has to start looking for other insulator materials. The study has now been published in the scientific journal Nature Electronics.

In a leap for battery research, machine learning gets scientific smarts

Scientists have taken a major step forward in harnessing machine learning to accelerate the design for better batteries: Instead of using it just to speed up scientific analysis by looking for patterns in data, as researchers generally do, they combined it with knowledge gained from experiments and equations guided by physics to discover and explain a process that shortens the lifetimes of fast-charging lithium-ion batteries.

It was the first time this approach, known as “scientific machine learning,” has been applied to battery cycling, said Will Chueh, an associate professor at Stanford University and investigator with the Department of Energy’s SLAC National Accelerator Laboratory who led the study. He said the results overturn long-held assumptions about how lithium-ion batteries charge and discharge and give researchers a new set of rules for engineering longer-lasting batteries.

The research, reported today in Nature Materials, is the latest result from a collaboration between Stanford, SLAC, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Toyota Research Institute (TRI). The goal is to bring together foundational research and industry know-how to develop a long-lived electric vehicle battery that can be charged in 10 minutes.

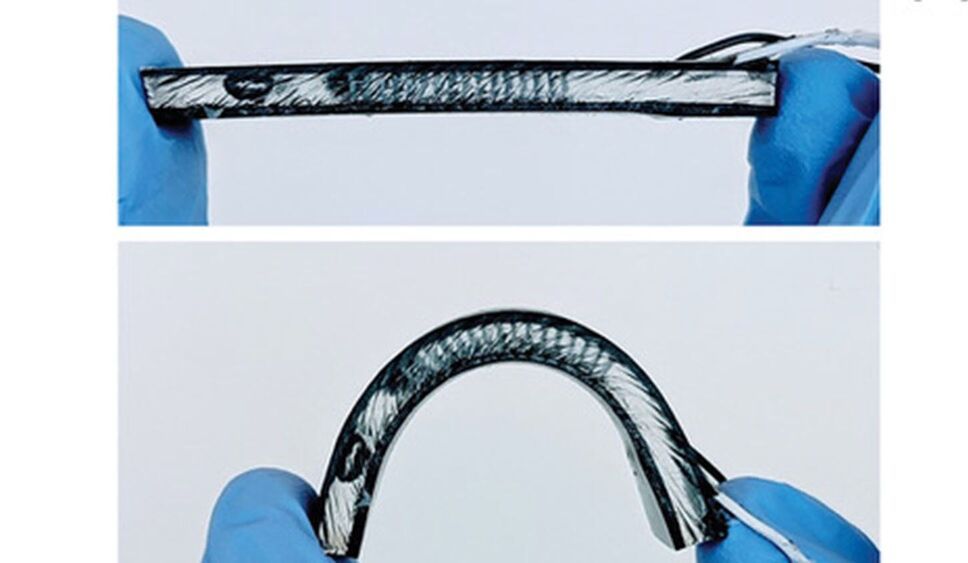

Reduced heat leakage improves wearable health device

North Carolina State University engineers continue to improve the efficiency of a flexible device worn on the wrist that harvests heat energy from the human body to monitor health.

In a paper published in npj Flexible Electronics, the NC State researchers report significant enhancements in preventing heat leakage in the flexible body heat harvester they first reported in 2017 and updated in 2020. The harvesters use heat energy from the human body to power wearable technologies —think of smart watches that measure your heart rate, blood oxygen, glucose and other health parameters—that never need to have their batteries recharged. The technology relies on the same principles governing rigid thermoelectric harvesters that convert heat to electrical energy.

Flexible harvesters that conform to the human body are highly desired for use with wearable technologies. Mehmet Ozturk, an NC State professor of electrical and computer engineering and the corresponding author of the paper, mentioned superior skin contact with flexible devices, as well as the ergonomic and comfort considerations to the device wearer, as the core reasons behind building flexible thermoelectric generators, or TEGs.

Israeli 5-minute battery charge aims to fire up electric cars

From flat battery to full charge in just five minutes—an Israeli start-up has developed technology it says could eliminate the “range anxiety” associated with electric cars.

Ultra-fast recharge specialists StoreDot have developed a first-generation lithium-ion battery that can rival the filling time of a standard car at the pump.

“We are changing the entire experience of the driver, the problem of ‘range anxiety’… that you might get stuck on the highway without energy,” StoreDot founder Doron Myersdorf said.

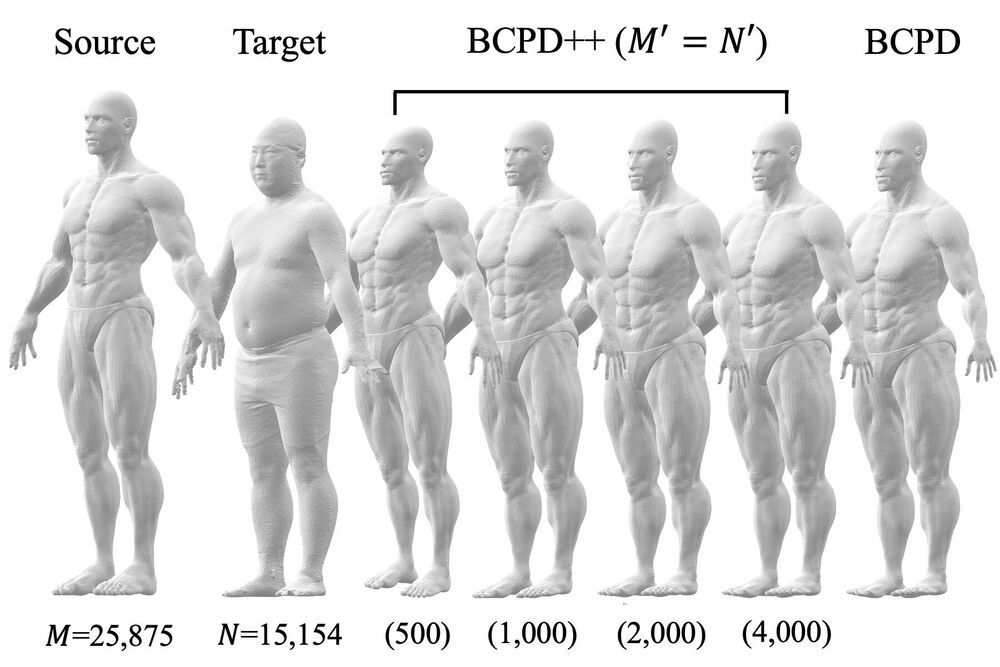

Key task in computer vision and graphics gets a boost

Non-rigid point set registration is the process of finding a spatial transformation that aligns two shapes represented as a set of data points. It has extensive applications in areas such as autonomous driving, medical imaging, and robotic manipulation. Now, a method has been developed to speed up this procedure.

In a study published in IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, a researcher from Kanazawa University has demonstrated a technique that reduces the computing time for non-rigid point set registration relative to other approaches.

Previous methods to accelerate this process have been computationally efficient only for shapes described by small point sets (containing fewer than 100000 points). Consequently, the use of such approaches in applications has been limited. This latest research aimed to address this drawback.