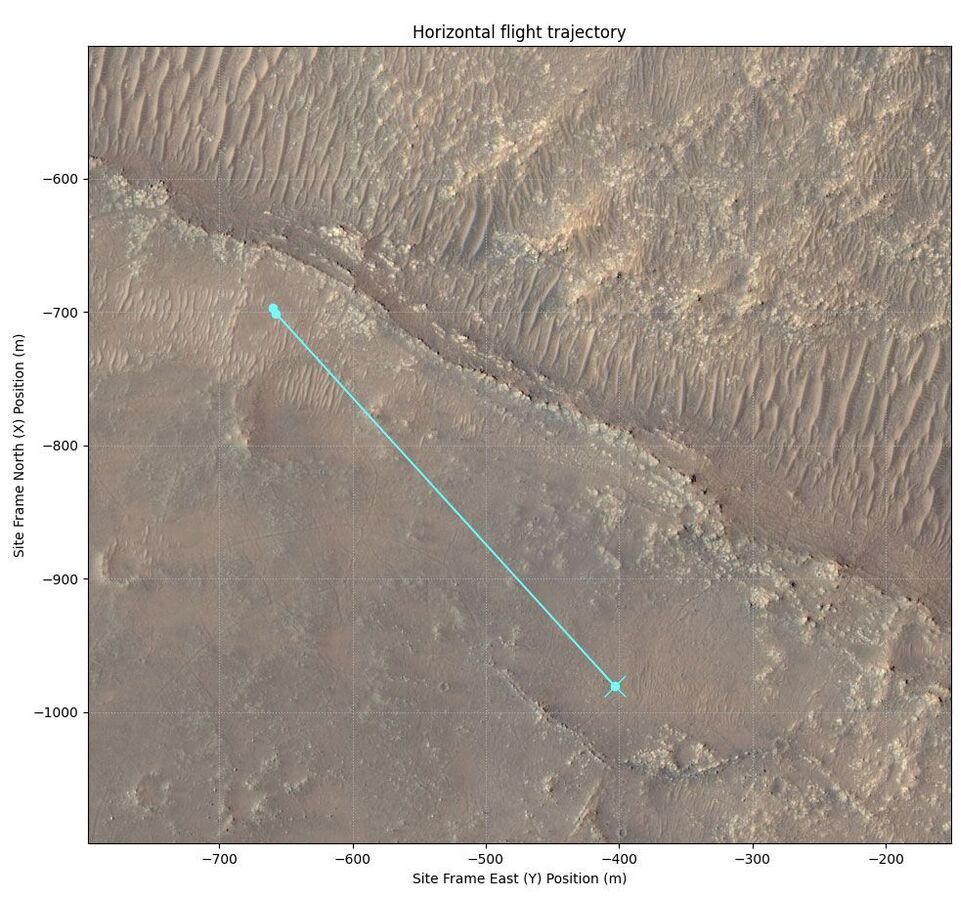

We’re heading northwest for the 11th flight of NASA’s Ingenuity Mars Helicopter, which will happen no earlier than Wednesday night, Aug. 4. The mission profile is designed to stay ahead of the rover – supporting its future science goals in the “South Séítah” region, where it will be able to gather aerial imagery in support of future Perseverance Mars rover surface operations in the area.

Here is how we plan to do it: On whatever day the flight takes place, we will start at 12:30 p.m. local Mars time (on Aug. 4, this would be 9:47 p.m. PDT/Aug. 5, 12:47 a.m. EDT). Ingenuity wakes up from its slumber and begins a pre-programmed series of preflight checks. Three minutes later, we’re off – literally – climbing to a height of 39 feet (12 meters), then heading downrange at a speed of 11 mph (5 meters per second).

And while Flight 11 is primarily intended as a transfer flight – moving the helicopter from one place to the other — we’re not letting the opportunity go to waste to take a few images along the way. Ingenuity’s color camera will take multiple photos en route, and then at the end of the flight, near our new airfield, we’ll take two images to make a 3D stereo pair. Flight 11 – from takeoff to landing –- should take about 130 seconds.