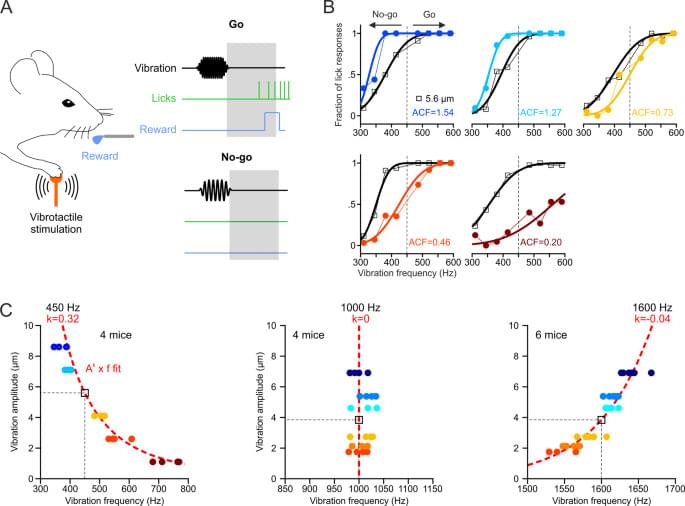

The features of vibrations provide key information on the surrounding environment. Here the authors show that a common computational principle underlies vibrotactile pitch perception in both mice and humans.

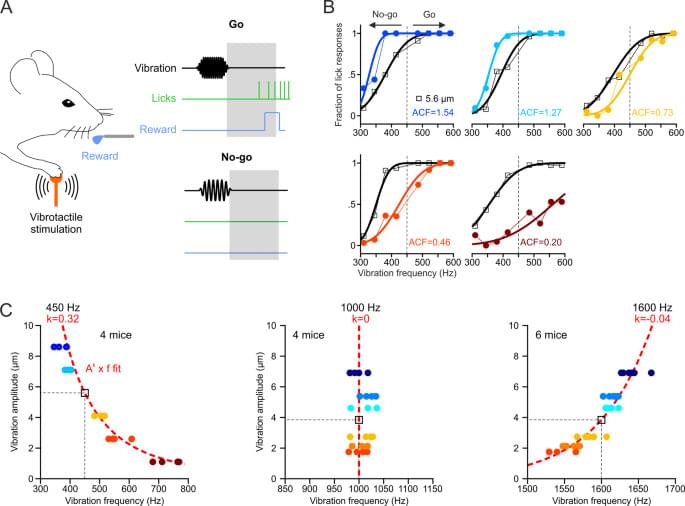

Hearing is thought to exist only in vertebrates and some arthropods, but not other animal phyla. Here, Xu and colleagues report that the earless nematode C. elegans senses airborne sound and engages in phonotaxis. Thus, hearing might have evolved multiple times independently in the animal kingdom, suggesting convergent evolution.

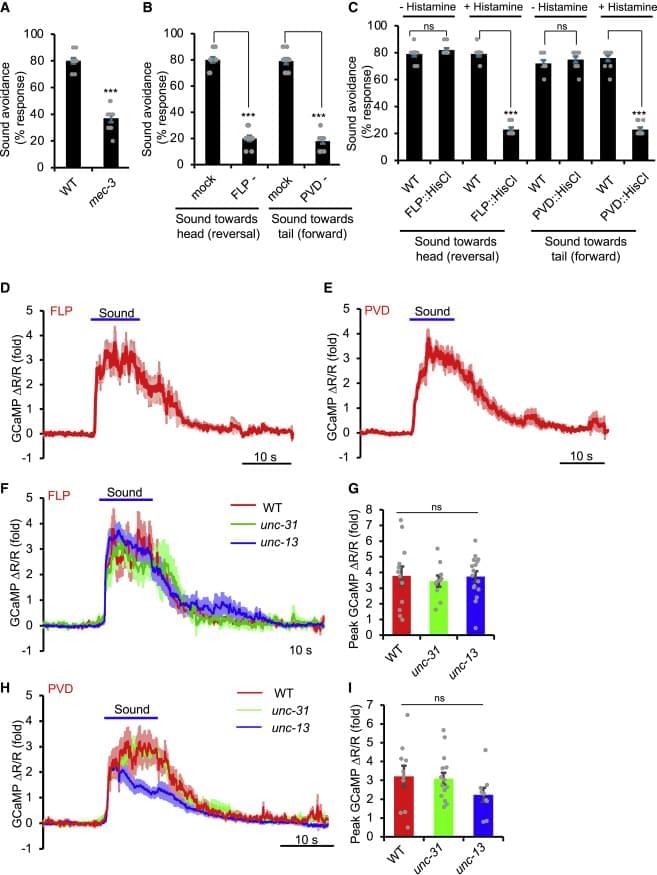

Few studies have examined and compared spousal concordance in different populations. This study aimed to quantify and compare spousal similarities in cardiometabolic risk factors and diseases between Dutch and Japanese populations.

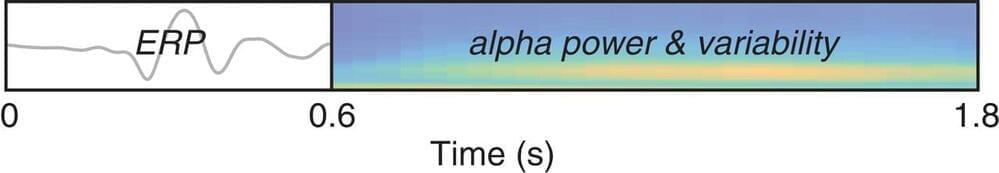

Our minds rarely stay still when left alone. Such trains of thought, however, may unfold in vastly different ways. Here, we combined electrophysiological recording with thought sampling to assess four types of thoughts: task-unrelated, freely moving, deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained. Parietal P3 was larger for task-related relative to task-unrelated thoughts, whereas frontal P3 was increased for deliberately constrained compared with unconstrained thoughts. Enhanced frontal alpha power was observed during freely moving thoughts compared with non-freely moving thoughts. Alpha-power variability was increased for task-unrelated, freely moving, and unconstrained thoughts. Our findings indicate these thought types have distinct electrophysiological signatures, suggesting that they capture the heterogeneity of our ongoing thoughts.

Our minds rarely stay still when left alone. Such trains of thought, however, may unfold in vastly different ways. Here, we combined electrophysiological recording with thought sampling to assess four types of thoughts: task-unrelated, freely moving, deliberately constrained, and automatically constrained. Parietal P3 was larger for task-related relative to task-unrelated thoughts, whereas frontal P3 was increased for deliberately constrained compared with unconstrained thoughts. Enhanced frontal alpha power was observed during freely moving thoughts compared with non-freely moving thoughts. Alpha-power variability was increased for task-unrelated, freely moving, and unconstrained thoughts. Our findings indicate these thought types have distinct electrophysiological signatures, suggesting that they capture the heterogeneity of our ongoing thoughts.

Humans spend much of their lives engaging with their internal train of thoughts. Traditionally, research focused on whether or not these thoughts are related to ongoing tasks, and has identified reliable and distinct behavioral and neural correlates of task-unrelated and task-related thought. A recent theoretical framework highlighted a different aspect of thinking—how it dynamically moves between topics. However, the neural correlates of such thought dynamics are unknown. The current study aimed to determine the electrophysiological signatures of these dynamics by recording electroencephalogram (EEG) while participants performed an attention task and periodically answered thought-sampling questions about whether their thoughts were 1) task-unrelated, 2) freely moving, 3) deliberately constrained, and 4) automatically constrained.

For years now, artificial intelligence has been hailed as both a savior and a destroyer. The technology really can make our lives easier, letting us summon our phones with a “Hey, Siri” and (more importantly) assisting doctors on the operating table. But as any science-fiction reader knows, AI is not an unmitigated good: It can be prone to the same racial biases as humans are, and, as is the case with self-driving cars, it can be forced to make murky split-second decisions that determine who lives and who dies. Like it or not, AI is only going to become an even more omnipresent force: We’re in a “watershed moment” for the technology, says Eric Schmidt, the former Google CEO.

A conversation with the former Google CEO Eric Schmidt.

By Saahil Desai

Astronomers are hot on the hunt for a giant planet in our outer Solar System. If it actually exists, that is.

While the several dwarf planets seem to point toward this unseen, larger-than-Earth object, it has eluded astronomers thus far. And not all of them take it as a matter of time — several astronomers think that it may just be a sampling bias that may not be as weird as it seems.

Here’s everything you need to know about the possible lost sibling of the solar system, from the basic theory to where it may be located, its orbit, and more.

Quantum physics is directly linked to consciousness: Observations not just change what is measured, they create it… Here’s the next episode of my new documentary Consciousness: Evolution of the Mind (2021), Part II: CONSCIOUSNESS & INFORMATION

*Subscribe to our YT channel to watch the rest of documentary (to be released in parts): https://youtube.com/c/EcstadelicMedia.

**Watch the documentary in its entirety on Vimeo ($0.99/rent; $1.99/buy): https://vimeo.com/ondemand/339083

***Join Consciousness: Evolution of the Mind public forum for news and discussions (Facebook group of 6K+ members): https://www.facebook.com/groups/consciousness.evolution.mind.

#Consciousness #Evolution #Mind #Documentary #Film

Good telescope that I’ve used to learn the basics: https://amzn.to/35r1jAk.

Get a Wonderful Person shirt: https://teespring.com/stores/whatdamath.

Alternatively, PayPal donations can be sent here: http://paypal.me/whatdamath.

Hello and welcome! My name is Anton and in this video, we will talk about the creation of first ever artificial cell mimics.

Links:

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-018-22263-3

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Artificial_cell.

Sacanna Lab 0 https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCT6gTHX182dXtgzywm7Bl2w/videos.

Support this channel on Patreon to help me make this a full time job:

https://www.patreon.com/whatdamath.

Bitcoin/Ethereum to spare? Donate them here to help this channel grow!

bc1qnkl3nk0zt7w0xzrgur9pnkcduj7a3xxllcn7d4

or ETH: 0x60f088B10b03115405d313f964BeA93eF0Bd3DbF

Space Engine is available for free here: http://spaceengine.org.

Enjoy and please subscribe.

Twitter: https://twitter.com/WhatDaMath.

Our cooling systems are heating the Earth as they consume fossil-fueled energy and release greenhouse gases. Air Conditioning use is expected to increase from about 3.6 billion units to 15 billion by 2050. So, how do we exit this cold room trap? What if I told you we could tap into space for electricity free air conditioning and other refrigeration tech?

Purchase RoboRock on Amazon: https://cli.fm/Roborockdock_matt_YT_Amazon.

or Visit RoboRock’s Official Website: https://cli.fm/Roborockdock_matt_YT

Watch Perovskite Solar Cells Could Be the Future of Energy: https://youtu.be/YWU89g7sj7s?list=PLnTSM-ORSgi7sp17ey2ydGRGBTFijdYCh.

Video script and citations:

https://undecidedmf.com/episodes/space-powered-cooling-may-b…-of-energy.

Follow-up podcast:

Video version — https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC4-aWB84Bupf5hxGqrwYqLA

Audio version — http://bit.ly/stilltbdfm.

👋 Support Undecided on Patreon!

Innovator, philanthropist, humanitarian — khaliya — discussing radical solutions for the global mental health crisis.

Khaliya (https://www.khaliya.net/) is a Columbia University-trained public health specialist and Harvard University-trained specialist in Global Mental Health and Refugee Trauma. She is also a Venture Partner for Gender Equity Diversity Investments (www.gedi.vc), a new female-led VC firm targeting high growth investments that deliver top-quartile returns and measurable impact towards the UN Sustainable Development Goals with a preliminary focus on health.

Formerly an aid worker in over 32 countries and a former Peace Corps Volunteer for the US State Department, she has won numerous awards for her international service. Khaliya was the youngest member of the WEF’s Futures Council on the Future of Health and Healthcare and her opinion pieces have run in the New York Times (International and Domestic Editions) as well as WiredUK.

Currently at work on a book on the future of mental health, Khaliya continues to be a sought after public speaker, having spoken at the Obama White House organized United States of Women Summit, the World Economic Forum’s Family Business Summit, the Vatican, Clinton Global Initiative, WiredHealth, WebSummit and at the United Nations General Assembly, among others.

Khaliya is next scheduled to speak at the G20 Women’s Summit in Milan, Italy, and the Ethical Assembly Summit in Lisbon, Portugal, both taking place in October, 2021.