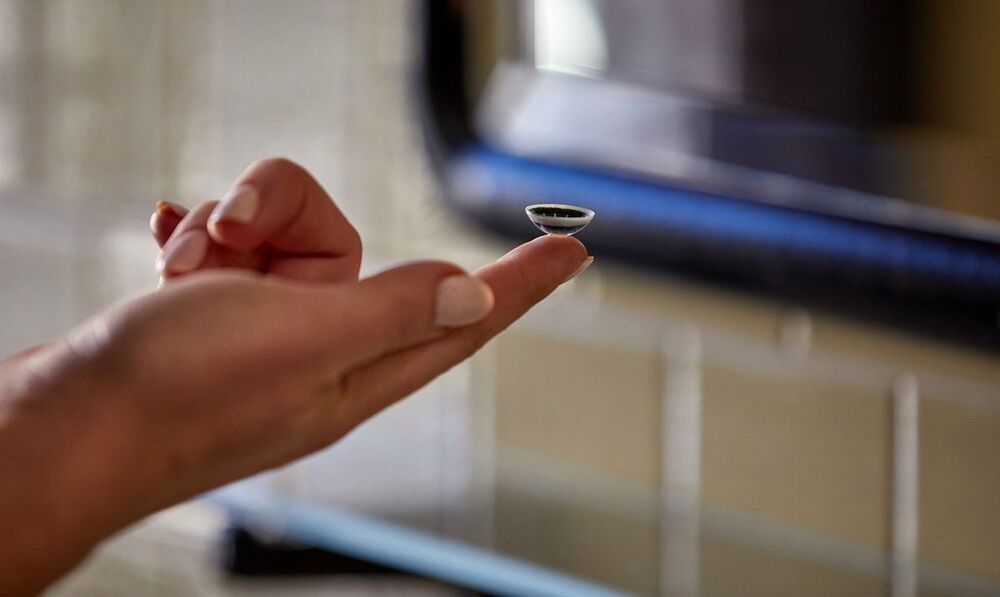

Mojo Vision has developed prototypes for contact lenses that enable people to see augmented reality images as overlays on the real world. And now it has teamed up with Menicon, Japan’s largest and oldest maker of contact lenses, to further develop the product.

Saratoga, California-based Mojo Vision has developed a smart contact lens with a tiny built-in display that lets you view augmented reality images on a screen sitting right on your eyeballs. It’s a pretty amazing innovation, but the company has to make sure that it works with contact lenses as they have been built for decades. The partnership with Menicon will help the company do that, Mojo Vision chief technology officer Mike Wiemer said in an interview with VentureBeat.

“It’s a development agreement, and it could turn into a commercial agreement,” Wiemer said. “I’m very excited to work with them.”