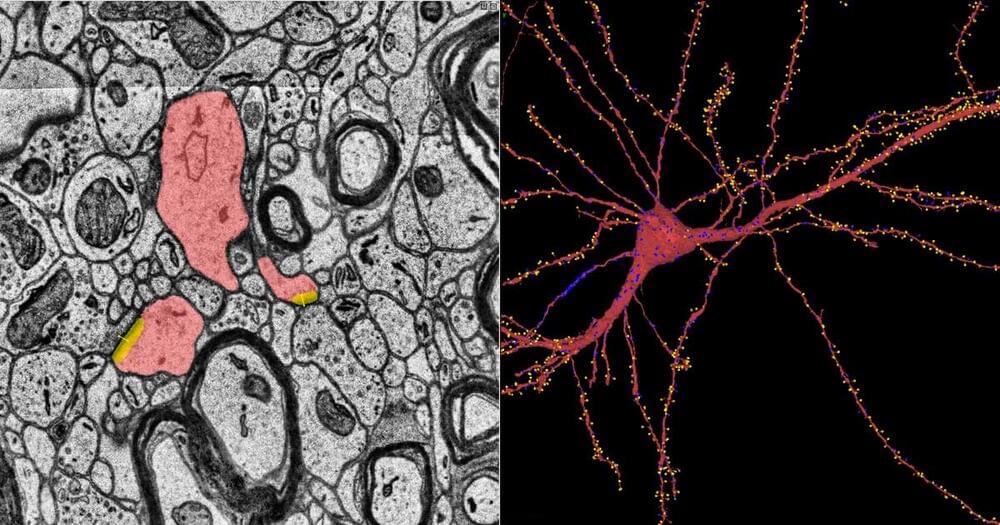

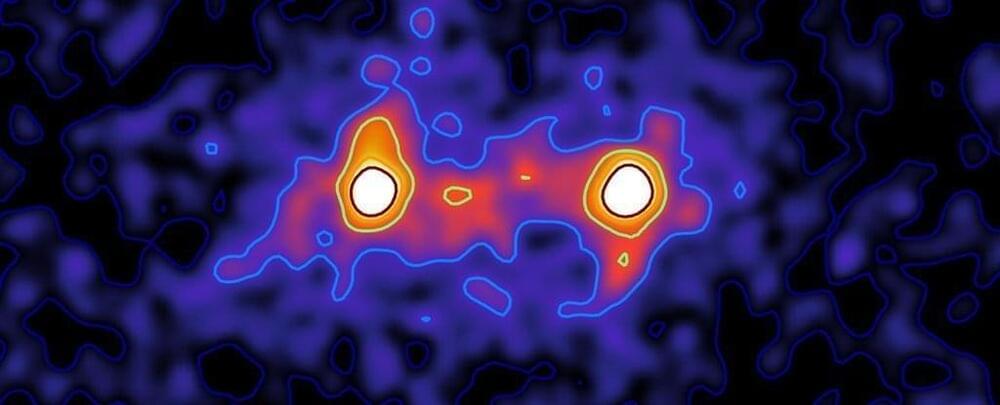

Researchers from Google and Harvard have released the most detailed map ever created of the human brain.

The map (called a connectome) contains “imaging data that covers roughly one cubic millimeter of brain tissue, and includes tens of thousands of reconstructed neurons, millions of neuron fragments, 130 million annotated synapses, 104 proofread cells, and many additional subcellular annotations and structures,” according to Google AI Blog.

Using a tool called the Neuroglancer (a cyberpunk novel if I’ve ever heard one!), you can browse that brain detail yourself.