SN20 continues to prep for a landmark orbital test flight.

The Starship SN20 vehicle performed a “static fire” test today (Dec. 29) at the company’s South Texas site, briefly igniting its Raptor engines while remaining anchored to the ground.

SN20 continues to prep for a landmark orbital test flight.

The Starship SN20 vehicle performed a “static fire” test today (Dec. 29) at the company’s South Texas site, briefly igniting its Raptor engines while remaining anchored to the ground.

We live in a very fast-changing world and quite an unpredictable one. In part, it is because we got lots of technological powers while our brain stays just the same as in pre-technological times. What do we teach children in this world? How can we help them to reflect on their thinking, get wiser in using the new technological powers, develop growth mindset and resilience, see the big picture and the interconnections within the complex systems (be that our body, ecological system, or the whole Universe)? We are trying to address these issues by teaching space science, AI and cognitive science, and existential risks and opportunities to pre-teens. In three years, the kids get an opportunity to talk to some of the most prominent thinkers in the field, reflect on deep questions, develop connections with specialists from multiple fields, from space law to ecology to virology, present their work at conferences. Check out our classes:

Art of Inquiry is an Online Science School for Young Explorers. We teach inquiry, thinking skills, and cutting-edge science. Our speakers and consultants are distinguished experts from academia, AI and space industry.

“The fungus in these experiments showed spatial recognition, memory and intelligence. It’s a conscious organism.”

Article: https://psyche.co/ideas/the-fungal-mind-on-the-evidence-for-…telligence.

(Clickable links at PaulStamets.com)

Nicholas P Money is a professor of biology and Western programme director at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio.

(See also my book wherein I postulated that mycelium has a consciousness: Mycelium Running: How Mushrooms Can Help Save the World.)

Source: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1878614621000246

#research #mycology #science #intelligence #mycelium #fungi #fungalmind #mushrooms #petri #consciousness #discovery

The telescope will join the worldwide effort.

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) successfully launched on Saturday, and it will soon be ready to reveal parts of the universe that have never been seen before including a very large, but very broody, cosmic object at the center of the galaxy.

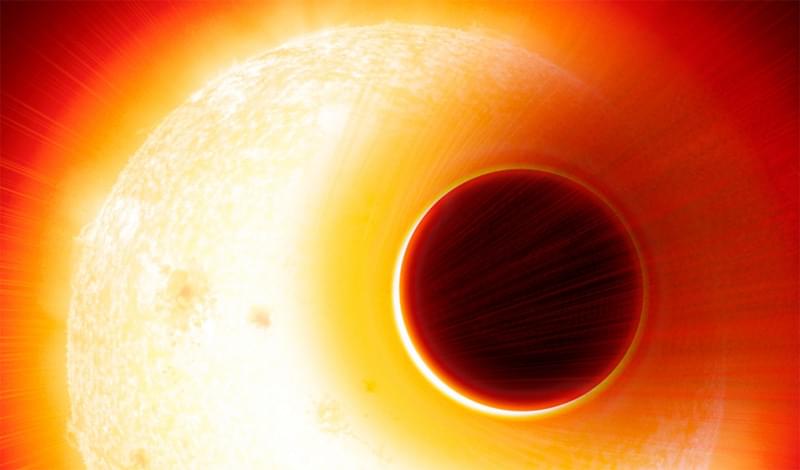

JWST will be joining in the ongoing, worldwide efforts to observe Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the center of the Milky Way. This elusive beast has been inferred from its gravitational effects, but imaging the black hole itself has proven elusive.

In April 2019, a group of more than 200 astronomers from all over the world unveiled the very first image of a black hole. Using the Event Horizon Telescope (EHT), an array of radio telescopes imaged the black hole at the center of the galaxy Messier 87 (M87). The EHT team compiled the image from eight telescopes on five continents working over an observing period of seven days.

TuSimple has stated that its “Driver Out” program is the first vital step in scaling its autonomous trucking operations on the TuSimple Autonomous Freight Network (AFN).

A robust AFN is now one step closer, following a successful 80-mile, driverless run in Arizona last week.

TuSimple announced its successful driverless ride via a recent press release, along with YouTube footage of the entire one-hour twenty-minute drive.

Chinese scientists are celebrating the success of a new hypersonic engine, according to reports. The past few months have been important for China in terms of the success of its hypersonic technologies.

Not only did the country get a new wind tunnel ready for tests of hypersonic weapons but it is also developing a hypersonic passenger plane. The fact that the country is in possession of a nuclear-capable hypersonic weapon system that is orbital in nature was also revealed less than a month ago.

Now, the successful testing of this engine will pave way for more advanced developments in components used for hypersonic flight, SCMP reported.