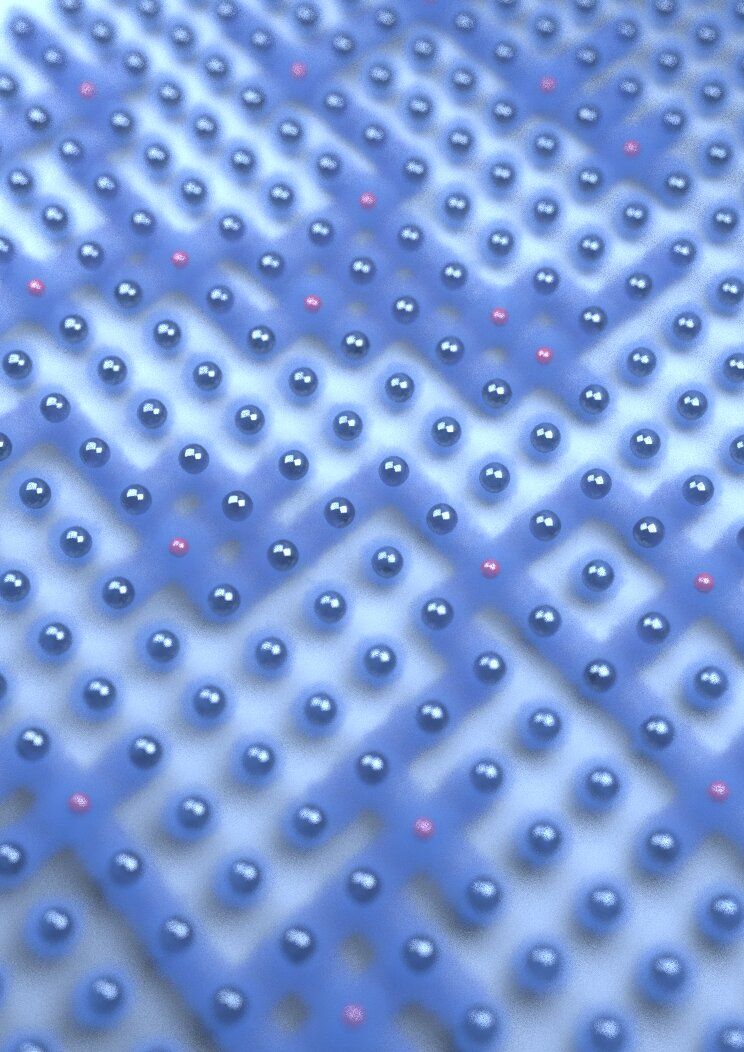

Most modern electronic devices rely on tiny, finely-tuned electrical currents to process and store information. These currents dictate how fast our computers run, how regularly our pacemakers tick and how securely our money is stored in the bank.

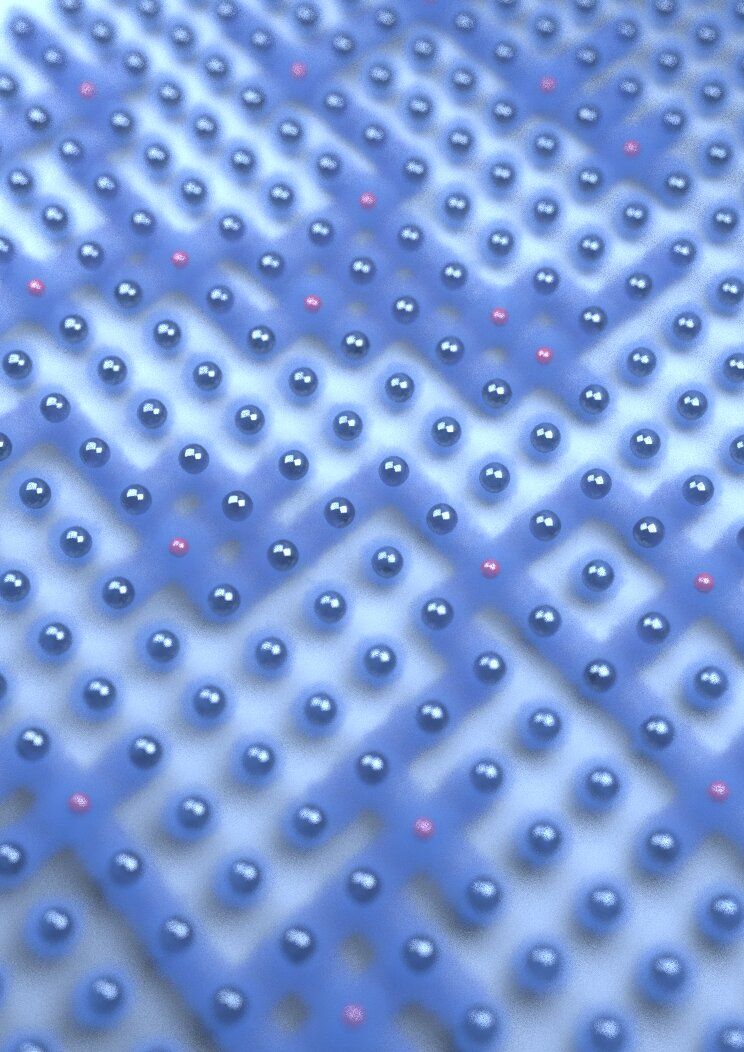

In a study published in Nature Physics, researchers at the University of British Columbia have demonstrated an entirely new way to precisely control such electrical currents by leveraging the interaction between an electron’s spin (which is the quantum magnetic field it inherently carries) and its orbital rotation around the nucleus.

“We have found a new way to switch the electrical conduction in materials from on to off,” said lead author Berend Zwartsenberg, a Ph.D. student at UBC’s Stewart Blusson Quantum Matter Institute (SBQMI). “Not only does this exciting result extend our understanding of how electrical conduction works, it will help us further explore known properties such as conductivity, magnetism and superconductivity, and discover new ones that could be important for quantum computing, data storage and energy applications.”