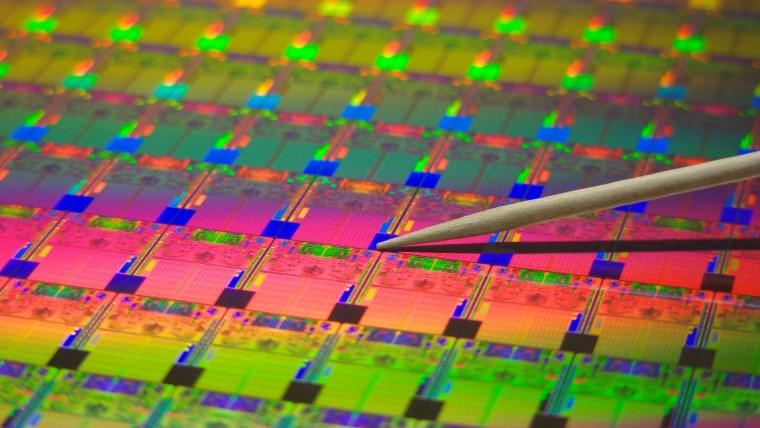

A new spin on one of the 20th century’s smallest but grandest inventions, the transistor, could help feed the world’s ever-growing appetite for digital memory while slicing up to 5% of the energy from its power-hungry diet.

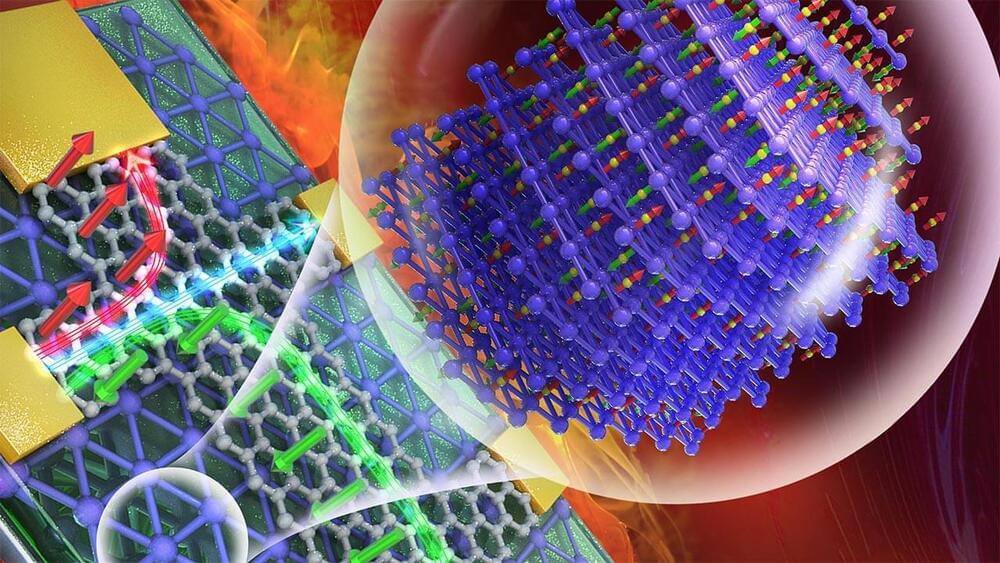

Following years of innovations from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Christian Binek and University at Buffalos Jonathan Bird and Keke He, the physicists recently teamed up to craft the first magneto-electric transistor.

Along with curbing the energy consumption of any microelectronics that incorporate it, the team’s design could reduce the number of transistors needed to store certain data by as much as 75%, said Nebraska physicist Peter Dowben, leading to smaller devices. It could also lend those microelectronics steel-trap memory that remembers exactly where its users leave off, even after being shut down or abruptly losing power.