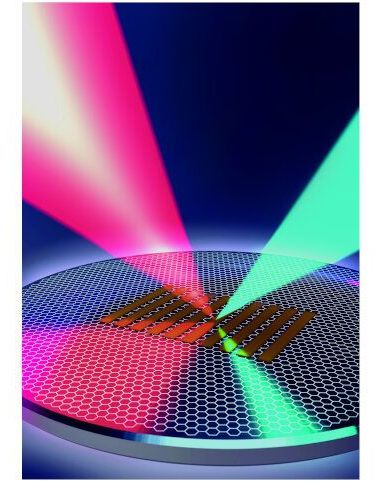

In a new study an international research team led by the University of Vienna has shown that structures built around a single layer of graphene allow for strong optical nonlinearities that can convert light. The team achieved this by using nanometer-sized gold ribbons to squeeze light, in the form of plasmons, into atomically-thin graphene. The results, which are published in Nature Nanotechnology are promising for a new family of ultra-small tunable nonlinear devices.

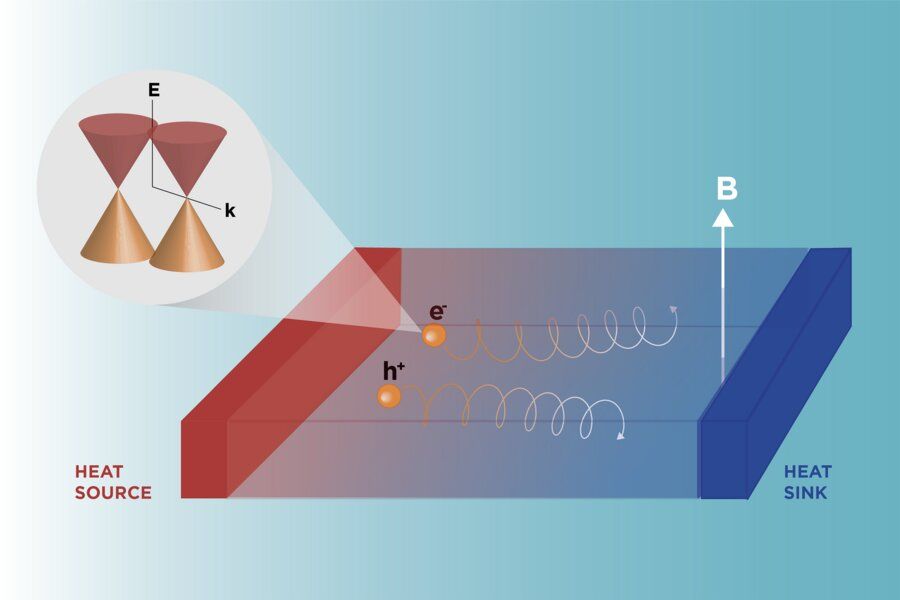

In the last years, a concerted effort has been made to develop plasmonic devices to manipulate and transmit light through nanometer-sized devices. At the same time, it has been shown that nonlinear interactions can be greatly enhanced by using plasmons, which can arise when light interacts with electrons in a material. In a plasmon, light is bound to electrons on the surface of a conducting material, allowing plasmons to be much smaller than the light that originally created them. This can lead to extremely strong nonlinear interactions. However, plasmons are typically created on the surface of metals, which causes them to decay very quickly, limiting both the plasmon propagation length and nonlinear interactions. In this new work, the researchers show that the long lifetime of plasmons in graphene and the strong nonlinearity of this material can overcome these challenges.

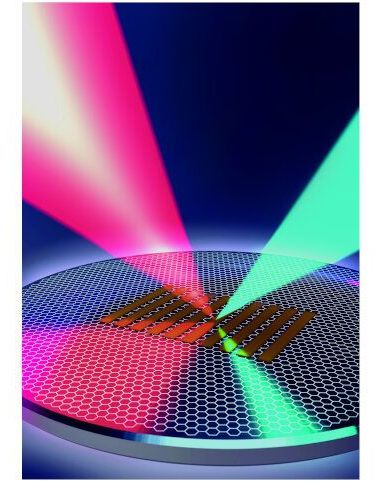

In their experiment, the research team led by Philip Walther at the University of Vienna (Austria), in collaboration with researchers from the Barcelona Institute of Photonic Sciences (Spain), the University of Southern Denmark, the University of Montpellier, and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (USA) used stacks of two-dimensional materials, called heterostructures, to build up a nonlinear plasmonic device. They took a single atomic layer of graphene and deposited an array of metallic nanoribbons onto it. The metal ribbons magnified the incoming light in the graphene layer, converting it into graphene plasmons. These plasmons were then trapped under the gold nanoribbons, and produced light of different colors through a process known as harmonic generation. The scientists studied the generated light, and showed that, the nonlinear interaction between the graphene plasmons was crucial to describe the harmonic generation.