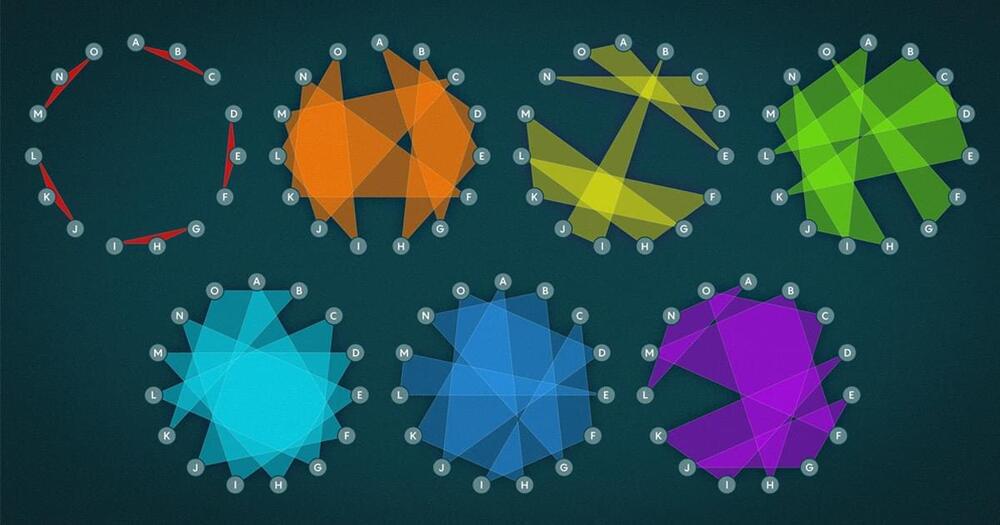

In 1973, Paul Erdős asked if it was possible to assemble sets of “triples” — three points on a graph — so that they abide by two seemingly incompatible rules. A new proof shows it can always be done.

Sustainable cell cultured mollusk seafood products — nikita michelsen, founder & CEO, pearlita foods.

Nikita Michelsen, is Founder & CEO of Pearlita Foods (https://www.pearlitafoods.com/), the world’s first cell-based mollusk company, which is developing sustainably & ethically grown products, like oysters and abalone, that are contaminant free without compromising flavor or nutrition.

Most recently Nikita served as both Director of Community and Director of Marketing of SynBioBeta and their Built With Biology premier innovation network for biological engineers, innovators, entrepreneurs, and investors who share a passion for using biology to build a better, more sustainable planet.

Nikita has a Bachelor’s Degree in Communication from UC Santa Barbara.

and a Master of Science in Information Science from Aalborg University.

Reimagining Nuclear Medicine — Dr. Stephen Moran, Ph.D., Global Program Head, Neuroendocrine Tumors & Other Radiosensitive Cancers, Advanced Accelerator Applications, Novartis

Dr. Stephen Moran, Ph.D., is Global Program Head, Neuroendocrine Tumors & Other Radiosensitive Cancers, for Advanced Accelerator Applications (AAA — https://www.adacap.com/), a Novartis company and also a member of the Oncology Development Unit Leadership Team at Novartis.

Prior to joining AAA, Dr. Moran was Global Head of Novartis Strategy, where he played a key role in defining the company’s strategy, prioritizing critical actions needed to deliver on the mission to discover new ways to extend and improve peoples’ lives. He also led numerous strategic initiatives, including gene therapy (AveXis, now Novartis Gene Therapies), RNA therapeutics (The Medicines Company), precision medicine and digital strategies.

Dr. Moran joined Novartis as Strategic Assistant to the CEO, a position he held for two years and prior to this, he was an associate principal at McKinsey & Company serving as a leader in the healthcare practice, where he focused on health system sustainability, research and development strategy, and the economic analysis of clinical interventions across disease pathways.

Dr. Moran holds a Bachelor of Arts and a Master of Science in Biochemistry from the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom, including an undergraduate exchange program at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT). He also received a Doctorate from the University of Oxford in Biophysics where he lectured on thermodynamics, quantum mechanics and electromagnetism as applied to biology.

Since April 1980, the overall yearly growth in energy prices is at its highest level. Gasoline prices increased by 11.2 per cent last month and a startling 59.9 per cent over the previous year, accounting for half of the monthly rise.

As per Government data released on Wednesday (July 13), in June, the United States saw a new peak of 9.1 per cent inflation. This faster-than-expected increase in the consumer price index (CPI) was driven by significant increases in gasoline prices, reports AFP. The US Labor Department has reported that this 9.1 per cent CPI spike over the past 12 months to June was the fastest increase in 40 years, the last such increase was witnessed in November 1981.

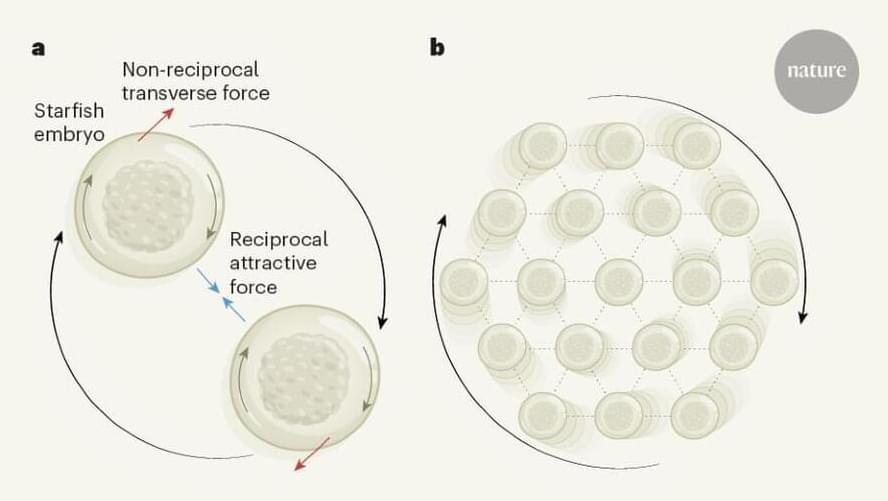

An investigation into a neutron-rich isotope of indium using a cutting-edge nuclear physics technique has begun to unravel the mysteries of how single particles behave inside the nucleus.

We have known that a nucleus is comprised of protons, which give an element its atomic number, and neutrons since the early 1930s. But how an individual proton or neutron behaves inside the heart of an atom is still poorly understood. Now, an international collaboration including scientists from Canada, China, Finland, France, Germany, Poland, Sweden, Switzerland, the UK and US has taken a step closer to understanding these complex interactions.

Nuclear physics researchers often look at elements with so-called ‘magic numbers’ of protons or neutrons, which are exceptionally well bound and thus highly stable. However, to learn about nuclear structure, nuclides with one fewer proton are used, known as a single proton hole. By investigating the electronic transitions, researchers can study the atomic, hyperfine structure of individual particles due to the interactions between electrons and the nucleus. This gives clues as to the nucleus’ magnetic and electric characteristics, which can then give a complete picture of how all protons and neutrons are distributed and interact inside a nucleus.

A French startup is turning fish skins into leather. It could help keep food waste out of landfills while using less polluting tanning methods.

More World Wide Waste Videos:

Meet The Woman Who Turns Trash Into High-End Furniture That Costs Thousands | World Wide Waste.

https://youtu.be/jvID1DzlVow.

A Garbage Mountain Burned For Months — But These People Couldn’t Leave | World Wide Waste.

How Sand Made From Crushed Glass Rebuilds Louisiana’s Shrinking Coast | World Wide Waste.

#Fish #WorldWideWaste #BusinessInsider.

Business Insider tells you all you need to know about business, finance, tech, retail, and more.

Visit us at: https://www.businessinsider.com.

Subscribe: https://www.youtube.com/user/businessinsider.

BI on Facebook: https://read.bi/2xOcEcj.

BI on Instagram: https://read.bi/2Q2D29T

BI on Twitter: https://read.bi/2xCnzGF

BI on Snapchat: https://www.snapchat.com/discover/Business_Insider/5319643143

Boot Camp on Snapchat: https://www.snapchat.com/discover/Boot_Camp/3383377771

Fish skin leather could fight restaurant waste | world wide waste | business insider.

Scientists have created an artificial intelligence that is able to think and learn like a baby.

The system is able to grasp the basic common sense rules of the world in the same way as humans can, the researchers who create it say.

The breakthrough could not only help advance AI research but also the ways we understand the human mind, scientists say.

Unlike much outdoor infrastructure, roads are not designed with any sun protection, making them prone to cracking and potentially unsafe to drive on.

Now, RMIT University engineers collaborated with Tyre Stewardship Australia (TSA) to discover the perfect blend that is both UV resistant and withstands traffic loads, with the potential to save governments millions on road maintenance annually. Their new research has found that crumb rubber, which is recycled from scrap tires, acts like sunscreen for roads and halves the rate of sun damage when mixed with bitumen.

Crumb rubber has already shown promise in making concrete stronger and more heat resistant. The new study found that the material acts so effectively as a sunscreen for roads that it actually makes the surface last twice as long as regular bitumen.