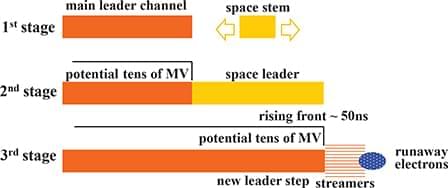

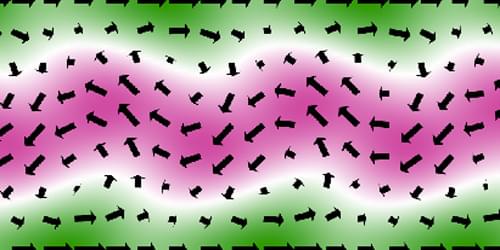

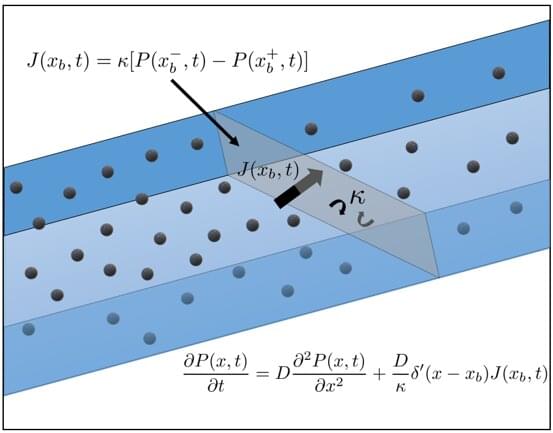

Lightning can produce multiband radio waves and high-energy radiations. Some of them are associated with the formation of lightning leaders. However, their generation mechanisms are not fully understood yet. Based on the understanding of thermal runaway electrons generated at the leader tip, we propose transition radiation of these runaway electrons as an alternative mechanism for producing very-high-frequency radio signals. Transition radiations are induced when runaway electrons cross the interfaces between lightning coronas and the air. By the use of estimated parameters of electron beams emerging from the leader tips, we calculate their coherent transition radiation and find that the energy spectra and radiation powers are consistent with some detection results from stepped leaders and even narrow bipolar events. Moreover, our model also predicts strong THz radiation during the stepped-leader formation. As a standard diagnosis technique of electron bunches, the proposed coherent transition radiation here may be able to reconstruct the actual properties of electron beams in the leader tips, which remains an open question.