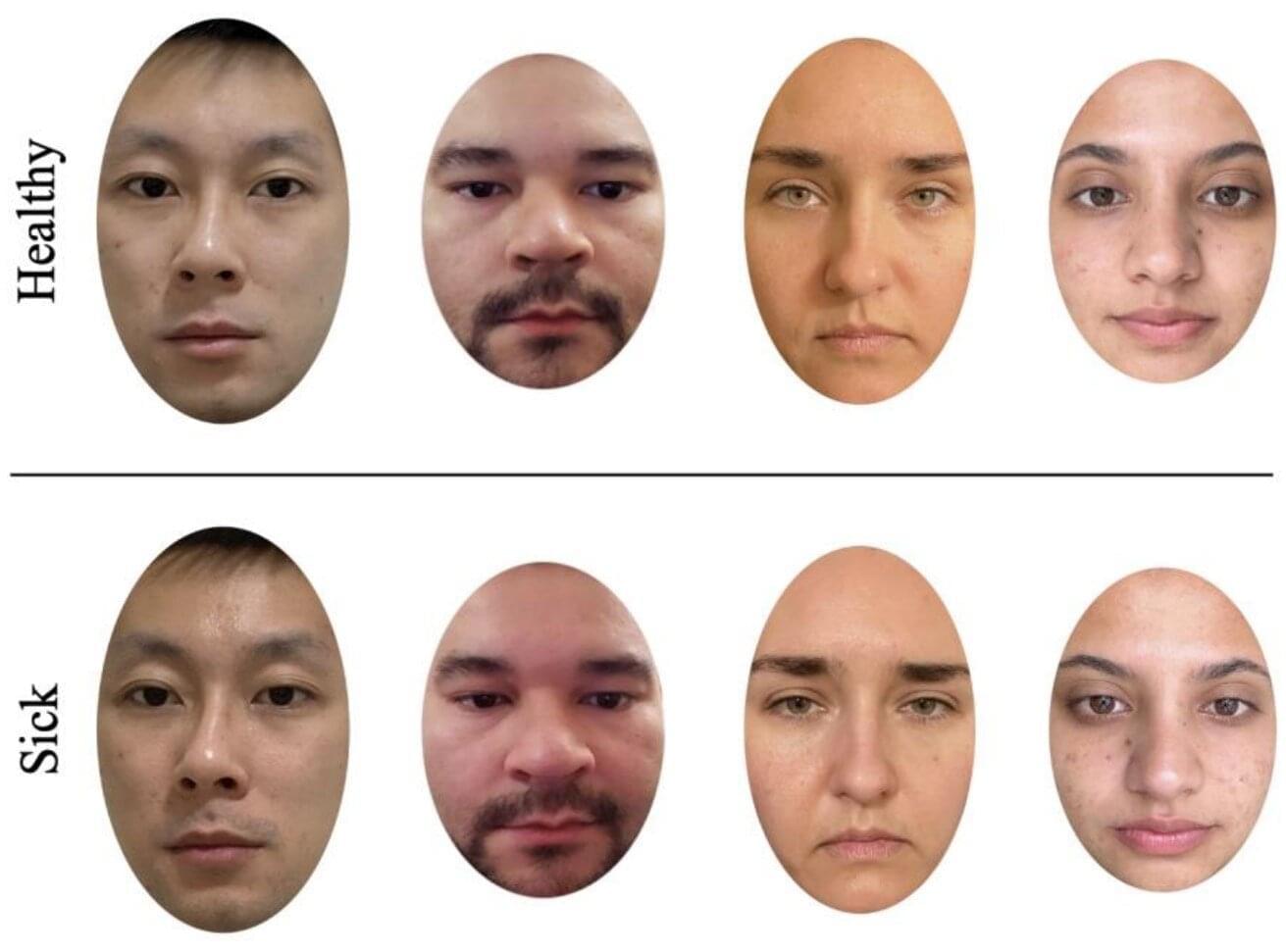

Most people have either been told that they don’t look well when they were sick, or thought that someone else looked ill at some point in their lives. People often use nonverbal facial cues, such as drooping eyelids and pale lips, to detect illness in others, potentially to prevent infection in themselves. A new study, published in Evolution and Human Behavior, finds that women are more sensitive to these subtle cues than men.

In past studies, participants have been asked to rate signs of illness in the faces of others, but some of these studies used manipulated photos or people who had artificially induced sicknesses in the photos. In the new study, the team wanted to see whether naturally sick individuals would be rated as sick-looking, or as having an expression of “lassitude,” by other individuals and whether the recognition differed by sex.

To do this, the team recruited 280 undergraduate students, of which 140 were male and 140 were female, to rate 24 photos. The photos consisted of 12 different faces in times of sickness and health.