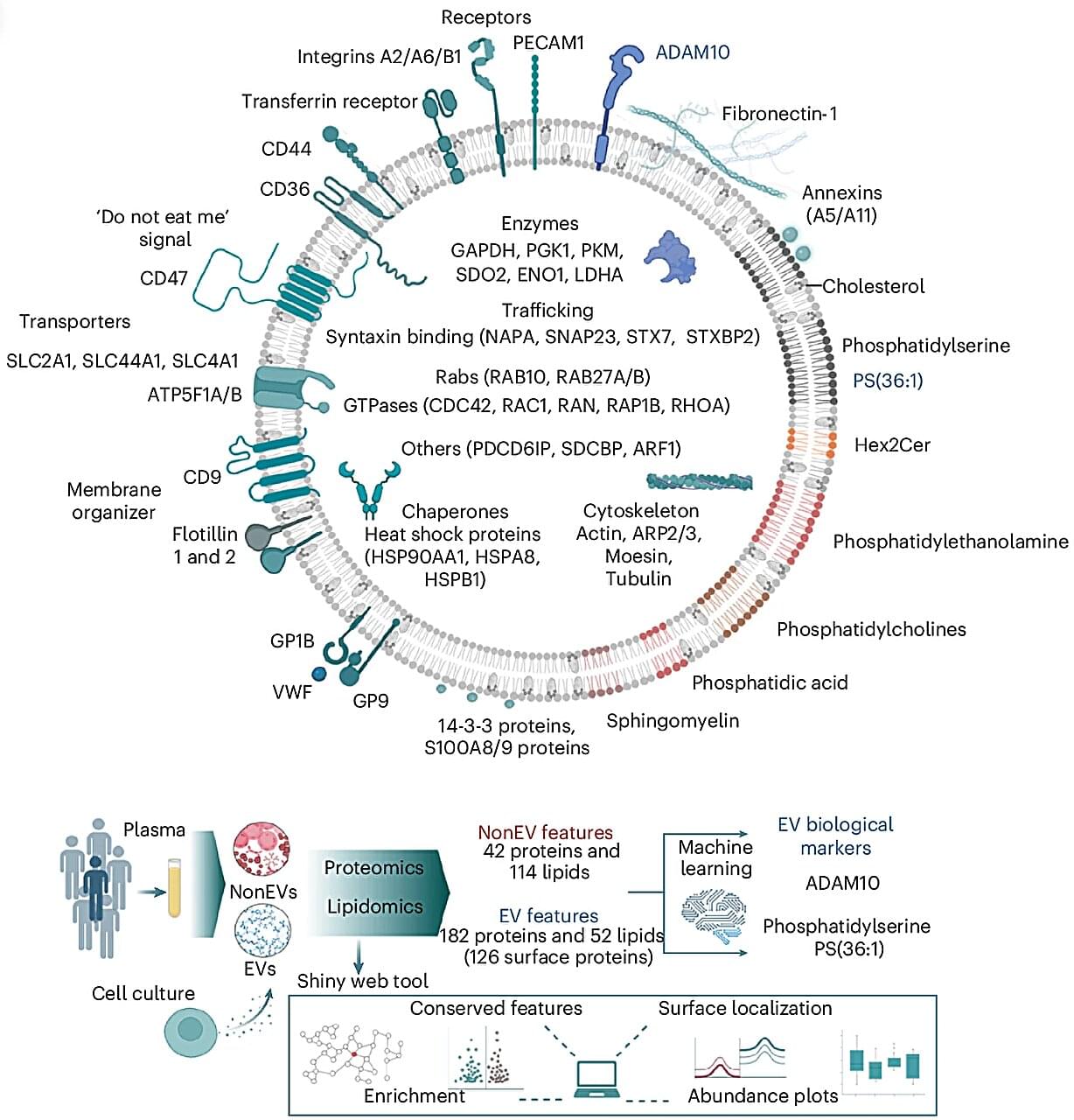

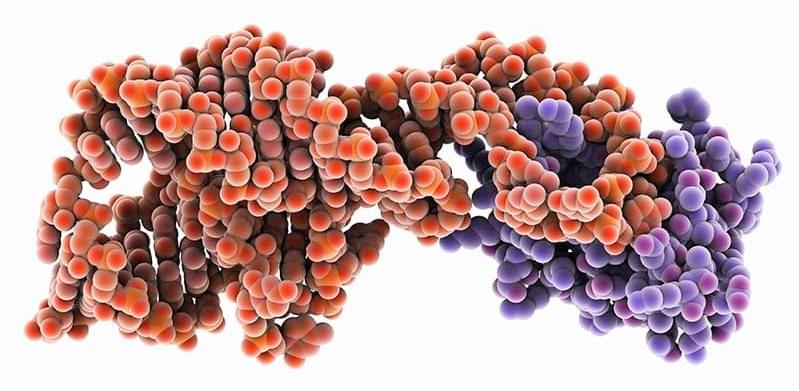

Every second, trillions of tiny parcels travel through your bloodstream—carrying vital information between your body’s cells. Now, scientists at the Baker Heart and Diabetes Institute have opened this molecular mail for the first time, revealing its contents in astonishing detail.

In research published in Nature Cell Biology, Professor David W. Greening and Dr. Alin Rai have mapped the complete molecular blueprint of extracellular vesicles (EVs)—nanosized particles in blood that act as the body’s secret messengers.

For decades, researchers have known that EVs exist, ferrying proteins, fats, and genetic material that mirror the health of their cells of origin. But because blood is a complex mixture—packed with cholesterol, antibodies, and millions of other particles—isolating EVs has long been one of science’s toughest challenges.