Discover 10 science backed anti inflammatory biohacks that improve health through simple food, sleep, stress, and lifestyle habits.

“This Perspective concludes that an MLA between 18–21 years is a scientifically supportable and socially coherent threshold for non-medical cannabis use.”

What should be the minimum legal age for recreational cannabis? This is what a recent study published in The American Journal on Drug and Alcohol Abuse hopes to address as a team of scientists investigated the benefits and challenges of raising the legal age for using recreational marijuana to 25, with the current age range being 18 to 21, depending on the country. This study has the potential to help researchers, legislators, and the public better understand the neuroscience behind the appropriate age for cannabis use.

For the study, the researchers examined brain development for individuals aged 18–25, specifically regarding brain maturation and whether this ceases before age 25. They note it depends on a myriad of factors, including sex, geographic region, and physiology. This study comes as Germany recently published several studies regarding legalizing recreational marijuana nationwide and marijuana use rates post-legalization. In the end, the researchers for this most recent study concluded that raising the minimum legal age for recreational cannabis use to 25 is unnecessary.

The study notes, “This Perspective concludes that an MLA between 18–21 years is a scientifically supportable and socially coherent threshold for non-medical cannabis use. Policy decisions should be informed not only by neurobiological evidence but also by legal, justice, sociocultural, psychological, and historical considerations.”

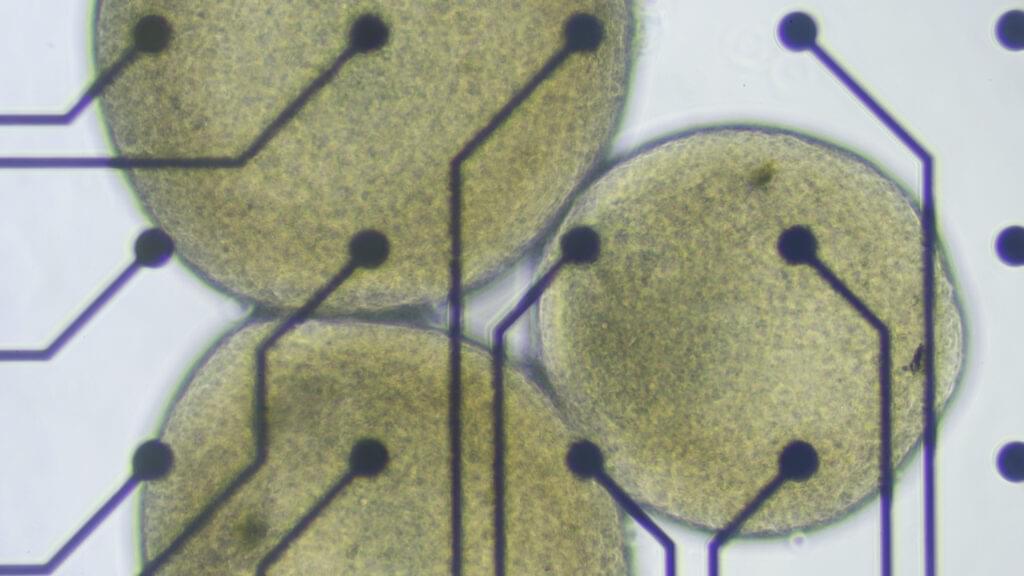

For the brain organoids in Lena Smirnova’s lab at Johns Hopkins University, there comes a time in their short lives when they must graduate from the cozy bath of the bioreactor, leave the warm, salty broth behind, and be plopped onto a silicon chip laced with microelectrodes. From there, these tiny white spheres of human tissue can simultaneously send and receive electrical signals that, once decoded by a computer, will show how the cells inside them are communicating with each other as they respond to their new environments.

More and more, it looks like these miniature lab-grown brain models are able to do things that resemble the biological building blocks of learning and memory. That’s what Smirnova and her colleagues reported earlier this year. It was a step toward establishing something she and her husband and collaborator, Thomas Hartung, are calling “organoid intelligence.”

Tead More

Another would be to leverage those functions to build biocomputers — organoid-machine hybrids that do the work of the systems powering today’s AI boom, but without all the environmental carnage. The idea is to harness some fraction of the human brain’s stunning information-processing superefficiencies in place of building more water-sucking, electricity-hogging, supercomputing data centers.

Despite widespread skepticism, it’s an idea that’s started to gain some traction. Both the National Science Foundation and DARPA have invested millions of dollars in organoid-based biocomputing in recent years. And there are a handful of companies claiming to have built cell-based systems already capable of some form of intelligence. But to the scientists who first forged the field of brain organoids to study psychiatric and neurodevelopmental disorders and find new ways to treat them, this has all come as a rather unwelcome development.

At a meeting last week at the Asilomar conference center in California, researchers, ethicists, and legal experts gathered to discuss the ethical and social issues surrounding human neural organoids, which fall outside of existing regulatory structures for research on humans or animals. Much of the conversation circled around how and where the field might set limits for itself, which often came back to the question of how to tell when lab-cultured cellular constructs have started to develop sentience, consciousness, or other higher-order properties widely regarded as carrying moral weight.

“It’s not a Jedi mind trick,” he writes in a statement. “This is what communication is. It is what humans do best, and it’s unique and amazing.”

Hasson argues that his research shows communication is really “a single act performed by two brains.” He believes that all brains naturally couple with the outside world, reacting to whatever stimuli we’re bombarded with. What makes humans different is our ability to couple without stimuli, according to Hasson. For example, if you show two monkeys a banana, their brains would likely react the same way, and the same goes for humans. However, if someone says the word banana to you, both you and the speaker would understand that you’re referring to the oblong, yellow fruit despite it not being physically present. This is something not all animals can achieve, which is why it’s so exciting for researchers like Hasson.

Studies show that brain synchronization happens in many settings. For instance, researchers found neural coupling can occur during chess matches or collaborative music-making sessions—two activities that require focus and creativity. On the other hand, a 2014 study published in PLUS One found that synchronization can occur during a much more physical activity: kissing. The experiment found heightened inter-brain connection when heterosexual couples were kissing each other’s lips rather than the backs of their hands.