Via Parameter Merging.

JNeurosci: Results from Veruki et al. show that activation of D1 receptors in rats reduces the excitability of AII amacrines by increasing the threshold of action potential initiation, suggesting a new role for DA in the retina.

🔗

Dopamine is an important neuromodulator found throughout the central nervous system that can influence neural circuits involved in sensory, motor, and cognitive functions. In the retina, dopamine is released by specific amacrine cells and plays a role in reconfiguring circuits for photopic vision. This adaptation takes place both in photoreceptors and at postreceptoral sites. The AII amacrine cell, which plays a crucial role for transmission of both scotopic and photopic visual signals, has been considered an important target of dopaminergic modulation, expressed as a change in the strength of electrical coupling mediated by gap junctions between the AIIs. It has been difficult, however, to find clear evidence for expression of dopamine receptors by AII amacrines.

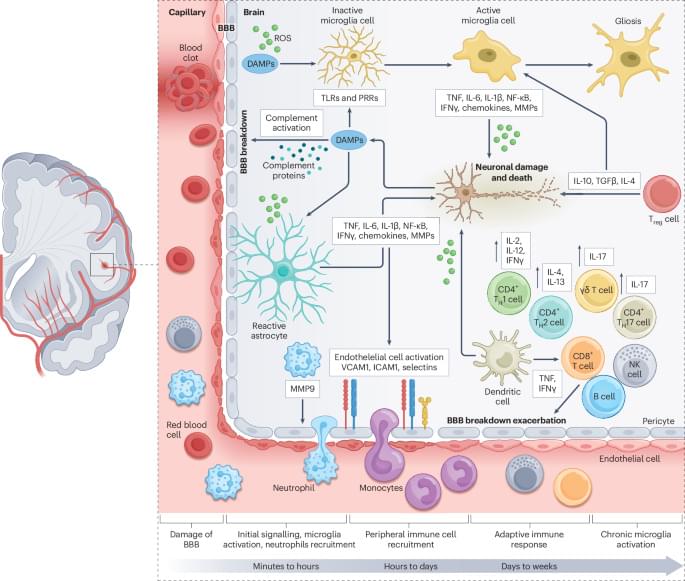

In this Review, Saef Izzy and colleagues examine the therapeutic potential of stem cells in stroke, with a focus on neural and mesenchymal stem cells. They explore how these stem cells interact with brain immune cells to modulate the inflammatory microenvironment, restore blood–brain barrier integrity and promote tissue repair following a stroke.

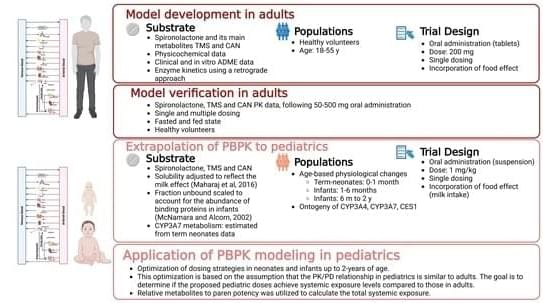

Background/Objectives: Spironolactone (SP) has been used off-label in pediatrics since its approval, but its use is challenged by limited pharmacokinetic (PK) data in adults and especially in children. Methods: Physiologically based pharmacokinetic (PBPK) models for SP and its active metabolites, canrenone (CAN) and 7α thio-methyl spironolactone (TMS), in adults were developed. These models aim to enhance understanding of SP’s PK and provide a basis for predicting PK and optimizing SP dosing in infants and neonates. Given SP’s complex metabolism, we assumed complete conversion to CAN and TMS by CES1 enzymes, fitting CES1-mediated metabolism to the parent-metabolite model using PK data. We incorporated ontogeny for CES1 and CYP3A4 and other age-related physiological changes into the model to anticipate PK in the pediatric population.

Behind every particle collision generated at the Large Hadron Collider is a multitude of technical feats. One of these is refrigeration on an industrial scale. To guide the particles, the thousands of superconducting magnets in the accelerator must be cooled to a temperature of close to absolute zero. This makes the LHC the largest cryogenic installation in the world: 23 of its 27 kilometers are maintained at 1.9 Kelvin (−271°C) using refrigerators in which superfluid helium circulates.

This unique cooling system needs to be further strengthened in preparation for the High-Luminosity LHC (HL-LHC), a major upgrade to the LHC that is scheduled to begin operation in 2030. On both sides of the two large experiments, ATLAS and CMS, more powerful focusing magnets and new types of cavities will considerably increase the number of collisions at each beam crossing or, in other words, the luminosity. This ultra-sophisticated equipment requires increased cooling power. Two new refrigerators are therefore being installed, in addition to the eight that are already needed for the existing accelerator.

The LHC’s refrigerators work on the same principle as the one in your kitchen, except that they are gigantic installations that occupy several buildings. Located on the surface, they include large compressors and an enormous cold box that contains the heat exchangers and the expansion turbines. These installations lower the helium temperature to 4.5 Kelvin (−268.6°C). Six compression units were installed in October.

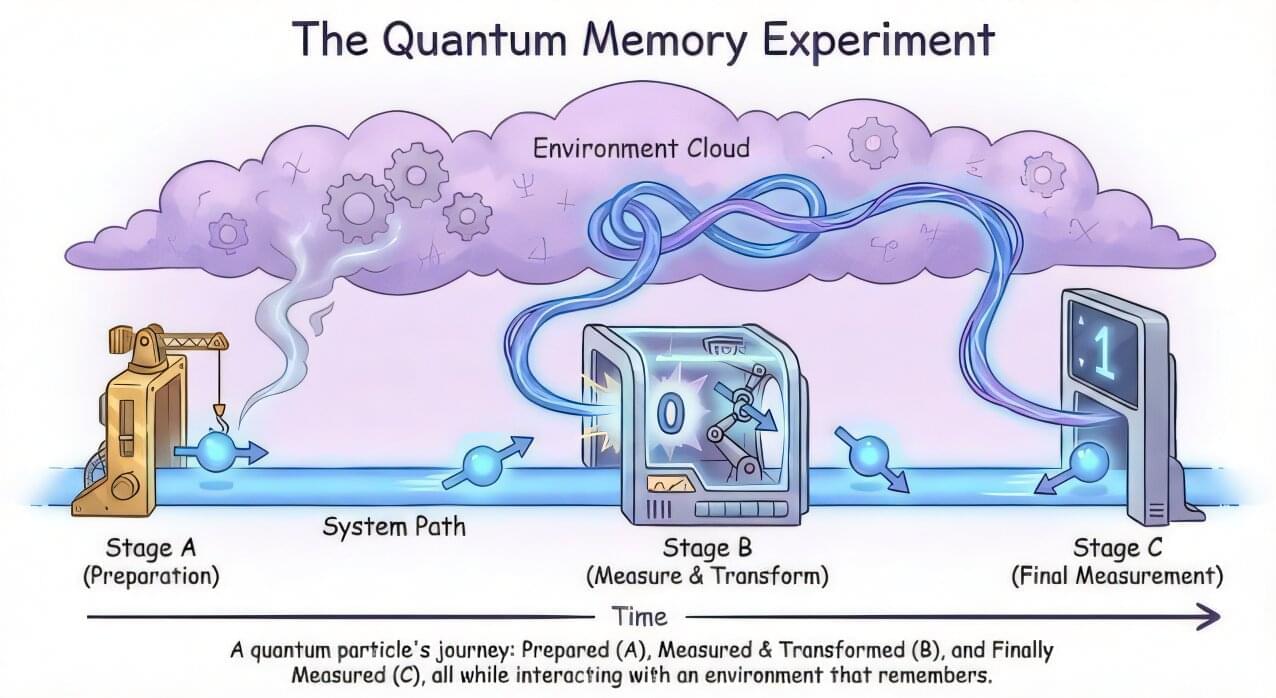

A team of Australian and international scientists has, for the first time, created a full picture of how errors unfold over time inside a quantum computer—a breakthrough that could help make future quantum machines far more reliable.

The researchers, led by Macquarie University’s Dr. Christina Giarmatzi, found that the tiny errors that plague quantum computers don’t just appear randomly. Instead, they can linger, evolve and even link together across different moments in time.

The team has made its experimental data and code openly available, and the full study is published in Quantum.

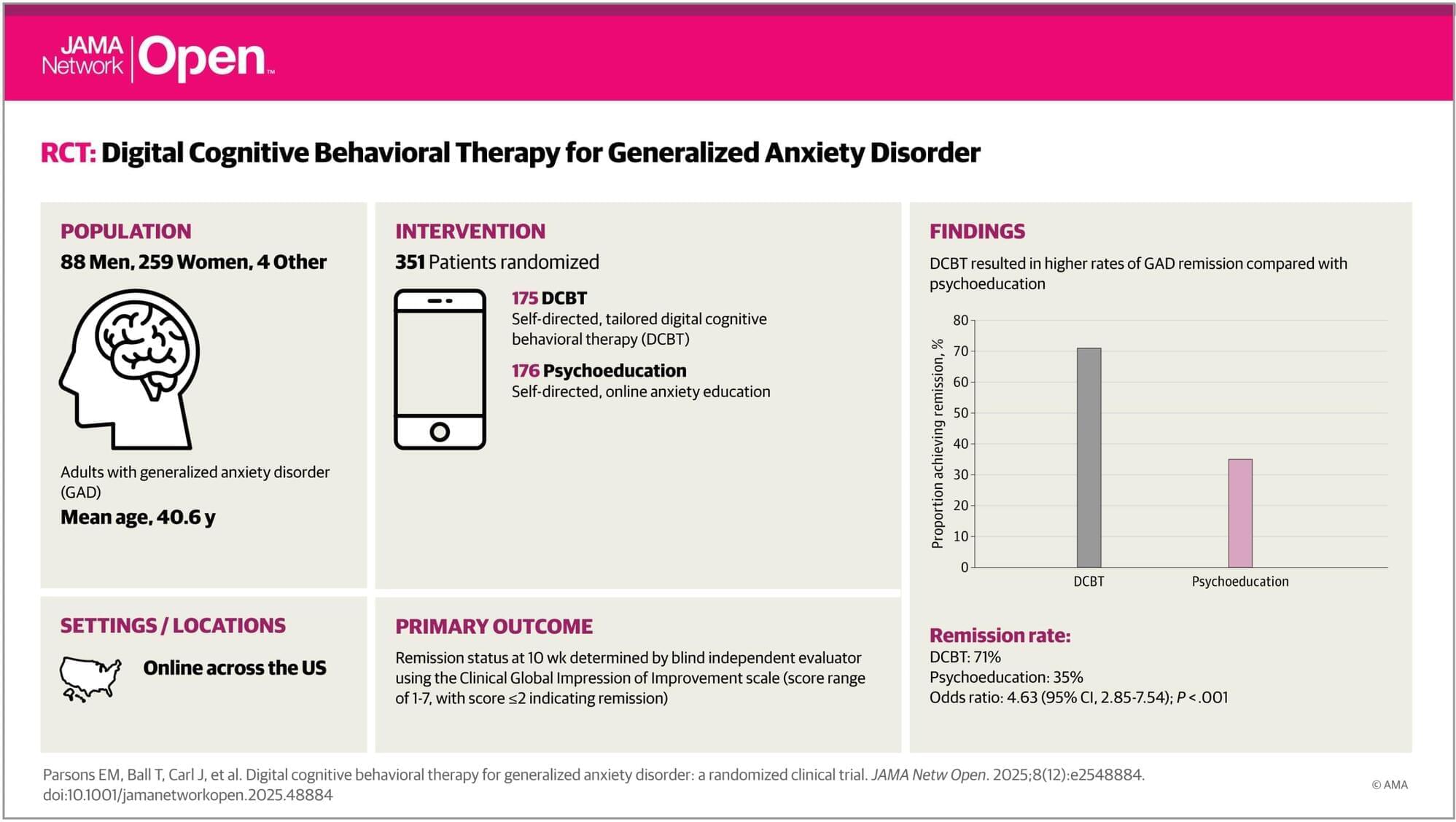

Big Health Inc, along with paid academic investigators, reports higher remission rates and lower anxiety symptom scores with their smartphone-delivered digital cognitive behavioral therapy, DaylightRx, compared with an online psychoeducation, also created by Big Health Inc.

Generalized anxiety disorder involves excessive, persistent, and uncontrollable anxiety with lifetime prevalence reported as 6%, alongside reduced quality of life, impaired social and occupational functioning, and increased health care utilization.

Cognitive behavioral therapy and pharmacotherapy are considered first-line treatments. Despite strong tolerability, efficacy, and cost-effectiveness, access remains limited due to a shortage of trained therapists, time burdens, and stigma.

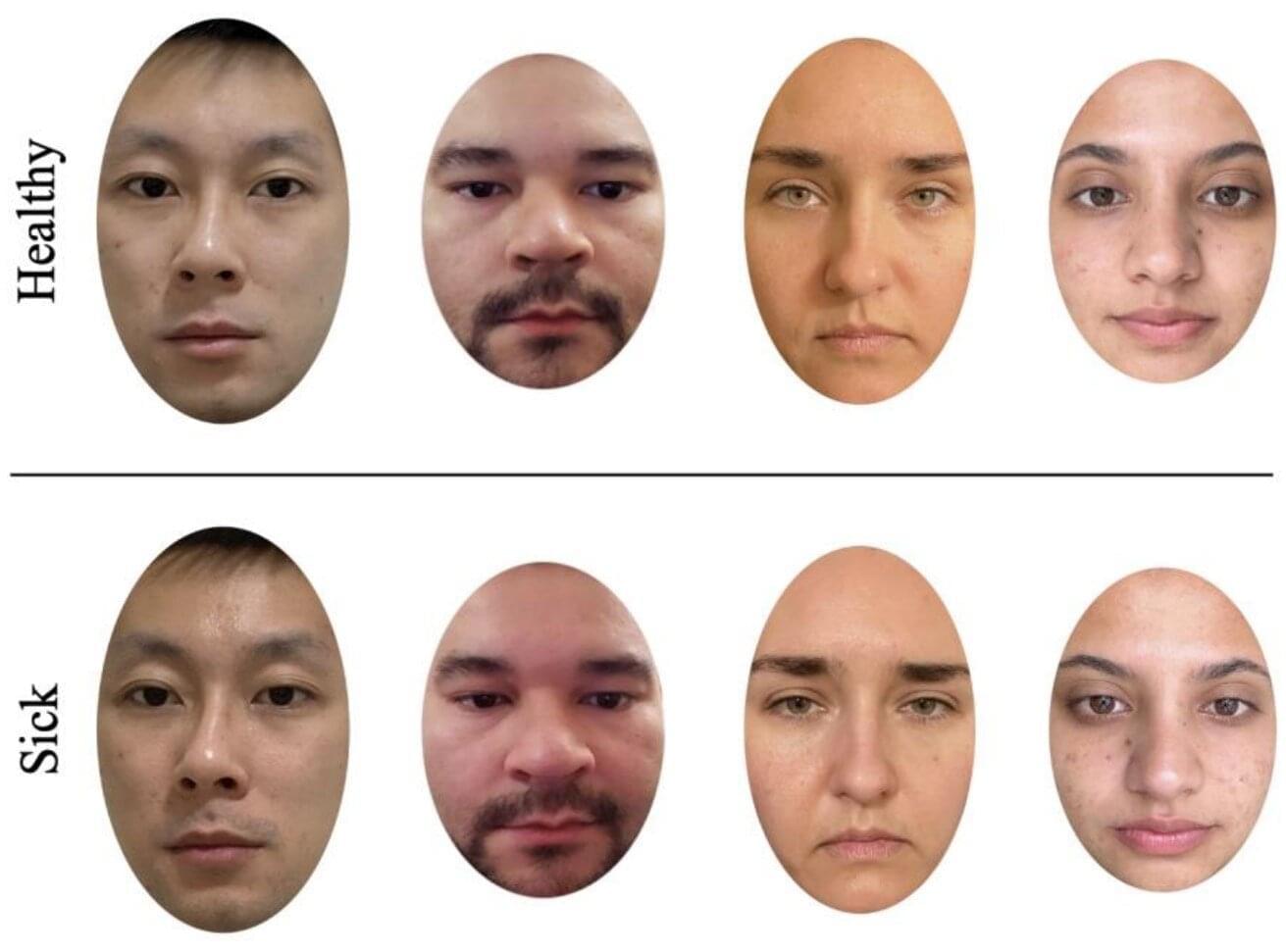

Most people have either been told that they don’t look well when they were sick, or thought that someone else looked ill at some point in their lives. People often use nonverbal facial cues, such as drooping eyelids and pale lips, to detect illness in others, potentially to prevent infection in themselves. A new study, published in Evolution and Human Behavior, finds that women are more sensitive to these subtle cues than men.

In past studies, participants have been asked to rate signs of illness in the faces of others, but some of these studies used manipulated photos or people who had artificially induced sicknesses in the photos. In the new study, the team wanted to see whether naturally sick individuals would be rated as sick-looking, or as having an expression of “lassitude,” by other individuals and whether the recognition differed by sex.

To do this, the team recruited 280 undergraduate students, of which 140 were male and 140 were female, to rate 24 photos. The photos consisted of 12 different faces in times of sickness and health.

The human brain is constantly processing information that unfolds at different speeds—from split-second reactions to sudden environmental changes to slower, more reflective processes such as understanding context or meaning.

A new study from Rutgers Health, published in Nature Communications, sheds light on how the brain integrates these fast and slow signals across its complex web of white matter connectivity pathways to support cognition and behavior.

Different regions of the brain are specialized for processing information over specific time windows, a property known as intrinsic neural timescales, or INTs for short.

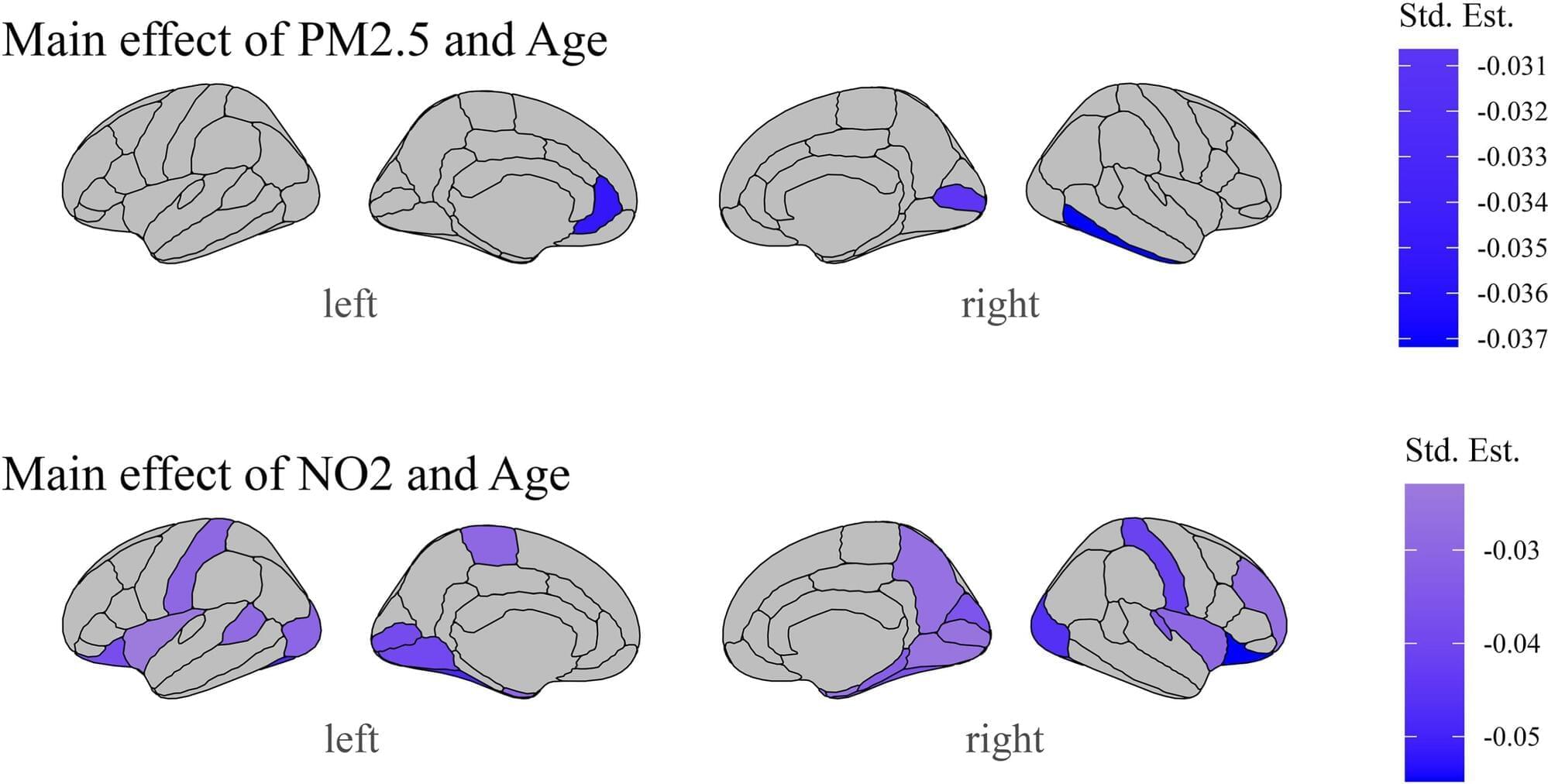

Physician-scientists at Oregon Health & Science University warn that exposure to air pollution may have serious implications for a child’s developing brain.

In a recent study published in the journal Environmental Research, researchers in OHSU’s Developmental Brain Imaging Lab found that air pollution is associated with structural changes in the adolescent brain, specifically in the frontal and temporal regions —the areas responsible for executive function, language, mood regulation and socioemotional processing.

Air pollution causes harmful contaminants, such as particulate matter, nitrogen dioxide and ozone, to circulate in the environment. It has been exacerbated over the past two centuries by industrialization, vehicle emissions, and, more recently, wildfires.