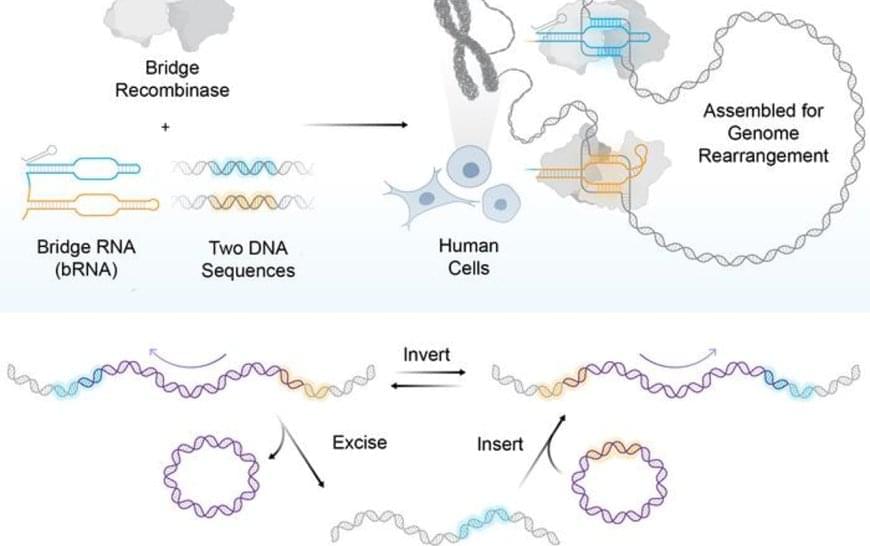

Bridge recombinases were discovered from parasitic mobile genetic elements that hijack bacterial genomes for their own survival. Presented last year in the journal Nature, the same team found these elements encode both a new class of structured guide RNA, which they named a “bridge RNA”, and a recombinase enzyme that rearranges DNA. The researchers repurposed this natural system by reprogramming the bridge RNA to target new DNA sequences, creating the foundation for a new type of precise gene editing tool they called bridge recombinases.

Starting with 72 different natural bridge recombinase systems isolated from bacteria, the team found that about 25% showed some activity in human cells, but most were barely detectable. Only one system, called ISCro4, showed enough measurable activity to enable further optimization. They then systematically improved both the protein and its RNA guide components, testing thousands of variations until they achieved 20% efficiency for DNA insertions and 82% specificity for hitting intended targets in the human genome.

While CRISPR uses a single guide RNA to target one DNA location, bridge RNAs are unique because they can simultaneously recognize two different DNA targets through distinct binding loops. This dual recognition enables the system to perform coordinated rearrangements such as bringing together distant chromosomal regions to excise genetic material or flipping existing sequences in reverse orientation. The system acts as molecular scaffolding that holds two DNA sites together while the recombinase enzyme performs the rearrangement reaction.

As a proof-of-concept, the researchers created artificial DNA constructs containing the same toxic repeat sequences that cause progressive neuromuscular decline in Friedreich’s ataxia patients. While healthy individuals carry fewer than 10 sequential copies of a three-letter DNA sequence, people with the disorder can harbor up to 1,700 copies, which interferes with normal gene function. The engineered ISCro4 successfully removed these repeats from the artificial constructs, in some cases eliminating over 80% of the expanded sequences.

The team also demonstrated that bridge recombinases could replicate existing therapeutic approaches by successfully removing the BCL11A enhancer, the same target disrupted in an FDA-approved sickle cell anemia treatment. And because bridge recombinases can move massive amounts of DNA, the technology could also help model the large-scale genomic rearrangements associated with cancers.

For decades, gene-editing science has been limited to making small, precise edits to human DNA, akin to correcting typos in the genetic code. The researchers are changing that paradigm with a universal gene editing system that allows for cutting and pasting of entire genomic paragraphs, rearranging whole chapters, and even restructuring entire passages of the genomic manuscript.