Some of Daniel Schmarchtenberger’s friends say you can be “Schmachtenberged”. It means realising that we are on our way to self-destruction as a civilisation, on a global level. This is a topic often addressed by the American philosopher and strategist, in a world with powerful weapons and technologies and a lack of efficient governance. But, as the catastrophic script has already started to be written, is there still hope? And how do we start reversing the scenario?

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

SpaceX Launches Upgraded Starlink Satellites After Issues with First Batch

SpaceX just did their second launch of V2 Mini satellites. Their first launch was two months ago and some satellites were lost as their new tech didn’t work on all satellites. Well, SpaceX has solved the bugs, and launched a second batch. Once the bugs are 100% solved, all future Starlink launches will only contain these new satellites.

These higher capacity satellites service about 33% more customers per pound of satellite than the V1.5 Starlink satellites.

SpaceX launched its second batch of upgraded Starlink satellites after some of the first version 2 (v2) buses deorbited earlier than planned. Liftoff aboard a Falcon 9 rocket occurred April 19 at 10:31 AM EDT (14:31 UTC) from Space Launch Complex 40 (SLC-40) at the Cape Canaveral Space Force Station.

This mission launched 21 of the Starlink v2 satellites into low Earth orbit. In December 2022, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) gave SpaceX approval to launch up to 7,500 next-generation Starlink satellites, known as Gen 2. That’s still a much smaller number than the original 29,988 the company originally requested.

These upgraded satellites will eventually be operating in circular orbits with altitudes of 525,530, and 535 km and inclinations of 53, 43, and 33 degrees, respectively, using frequencies in the Ku-and Ka-band.

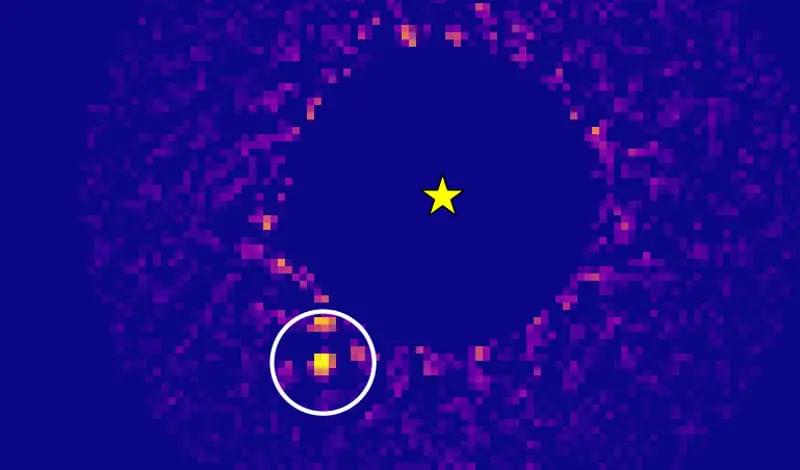

New exoplanet seen via direct imaging

The discovery of HIP 99,770 b, a new exoplanet located 133 light years away, is reported in the journal Science. A team of astronomers used a new detection method that combines direct imaging with astrometry.

As of today, there are 5,363 confirmed exoplanets in 3,960 planetary systems. However, only a handful have been seen via direct imaging. Exoplanets are extremely faint compared with their parent stars, making it difficult to spot them in visible light.

Could Aluminum Nitride Produce Quantum Bits?

Quantum computers have the potential to break common cryptography techniques, search huge datasets and simulate quantum systems in a fraction of the time it would take today’s computers. But before this can happen, engineers need to be able to harness the properties of quantum bits or qubits.

Currently, one of the leading methods for creating qubits in materials involves exploiting the structural atomic defects in diamond. But several researchers at the University of Chicago and Argonne National Laboratory believe that if an analogue defect could be engineered into a less expensive material, the cost of manufacturing quantum technologies could be significantly reduced. Using supercomputers at the National Energy Research Scientific Computing Center (NERSC), which is located at the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (Berkeley Lab), these researchers have identified a possible candidate in aluminum nitride. Their findings were published in Nature Scientific Reports.

“Silicon semiconductors are reaching their physical limits—it’ll probably happen within the next five to 10 years—but if we can implement qubits into semiconductors, we will be able to move beyond silicon,” says Hosung Seo, University of Chicago Postdoctoral Researcher and a first author of the paper.

OpenAI’s FIRST Robot SHOCKS the World | ChatGPT

What if I told you Open AI had a new robot coming out infused with ChatGPT? Well, they do.

If you like this content, please consider subscribing, as we can be your one stop shop to satisfy your AI needs! We have all the scoops on the world’s latest artificial intelligence projects!

► For business related matters relating to our channel (including media & advertising) please contact: [email protected].

Please note, the videos published on this channel fall under the remits of Fair Use. I educate viewers on such topics as, but are not limited to: construction, engineering and architecture, and I produce well-researched and unique content, with MY OWN COMMENTARY, that aligns with YouTube policies and guidelines.

► Copyright Disclaimer under Section 107 of the copyright act 1976, allowance is made for fair use for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, scholarship, and research. Fair use is a use permitted by copyright statute that might otherwise be infringing.

For any copyright related matters, please contact: [email protected]

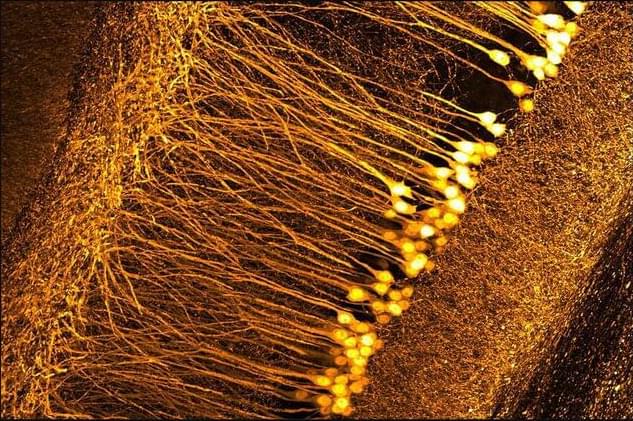

Inspired by the sea and the sky, a biologist invents a new kind of microscope

Enter Fabian Voigt, a molecular biologist at Harvard University and inventor of the new design. He was reading a book about animal vision when he encountered the odd case of scallops’ eyes. Unlike most animals, whose eyes feature retinas that send images to the brain, scallops have mantles covered with hundreds of tiny blue dots, each of which contains a curved mirror at its back. As light passes through each eye’s lens, its inner mirror reflects the light back onto the creature’s photoreceptors to create an image that then allows the scallop to respond to its environment.

An amateur astronomer since he was a teenager, Voigt realized the scallop’s eye design resembled a kind of telescope invented nearly 100 years ago called the Schmidt telescope. The Kepler Space Telescope, which orbits Earth, uses a similar curved mirror design to magnify far-away light from exoplanets. Voigt realized that by shrinking the mirror, using lasers for light, and filling the space between the mirror and the detector with liquid to minimize light scattering, the design could be adapted to fit inside a microscope.

So, Voigt and colleagues built a prototype based on those specs. Light enters from the top, passes through a curved plate that corrects for the mirror’s curvature, then bounces off a mirror to hit a sample and magnify it. The curved mirror can magnify the image much like a lens, Voigt says. It allows researchers to look at samples suspended in any kind of liquid, simplifying the process. Voigt says the design could be particularly useful for researchers who study organs or even entire organisms, such as mice or embryos, that have been made completely transparent by artificially removing their pigment.

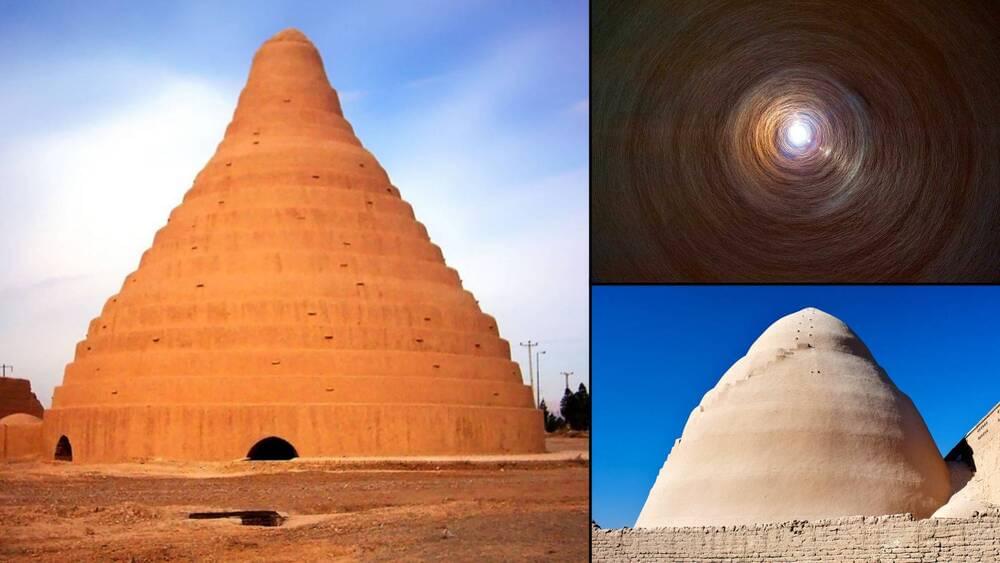

Ancient hi-tech freezers that kept ice cold — even during desert summers!

Most of the households in the world today have refrigerators but need to keep food on lower temperatures is not new. People harvested ice and snow as early as 1,000 BC and there are written evidence that ancient Chinese, Jews, Greeks and Romans used to do this. But what people that lived in deserts did? Some of them, like Persians, built an advanced mechanism for this particular purpose.

By 400 BC, Persian engineers had mastered the technique of storing ice in the middle of summer in the desert. The ice was brought in during the winters from nearby mountains in bulk amounts, and stored in their own freezers called Yakhchal, or ice-pit.

These ancient refrigerators were used primarily to store ice for use in the summer, as well as for food storage, in the hot, dry desert climate of Iran. The ice was also used to chill treats for royalty during hot summer days and to make faloodeh, the traditional Persian frozen dessert.