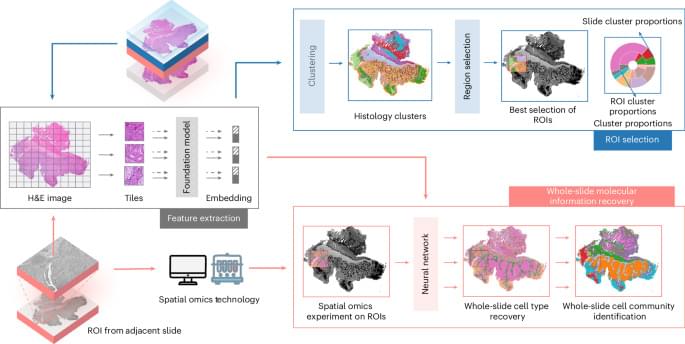

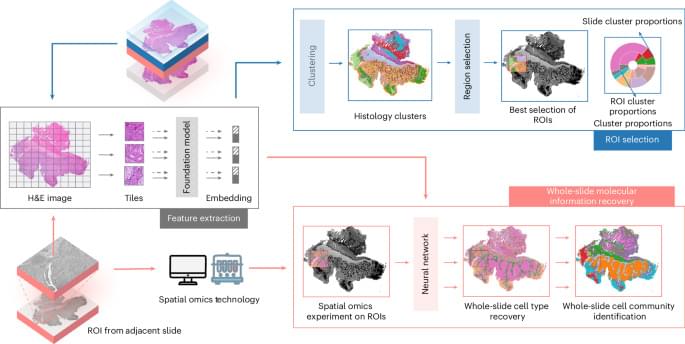

Yuan et al. present S2-omics, an end-to-end workflow that automatically identifies regions of interest in histology images to maximize molecular information capture in spatial omics experiments.

Protein homeostasis, or proteostasis, is essential for cellular proteins to function properly. The buildup of abnormal proteins (such as damaged, misfolded, or aggregated proteins) is associated with many diseases, including cancer. Therefore, maintaining proteostasis is critical for cellular health. Currently, genetic methods for modulating proteostasis, such as RNA interference and CRISPR knockout, lack spatial and temporal precision. They are also not suitable for depleting already-synthesized proteins. Similarly, molecular tools like PROTACs and molecular glue face challenges in drug design and discovery. To directly control targeted protein degradation within cells, we introduce an intrabody-based optogenetic toolbox named Flash-Away integrates the light-responsive ubiquitination activity of the RING domain of TRIM21 for protein degradation, coupled with specific intrabodies for precise targeting. Upon exposure to blue light, Flash-Away enables rapid and targeted degradation of selected proteins. This versatility is demonstrated through successful application to diverse protein targets, including actin, MLKL, and ALFA-tag fused proteins. This innovative light-inducible protein degradation system offers a powerful approach to investigate the functions of specific proteins within physiological contexts. Moreover, Flash-Away presents potential opportunities for clinical translational research and precise medical interventions, advancing the prospects of precision medicine.

Researchers at Baylor College of Medicine have discovered a natural mechanism that clears existing amyloid plaques in the brains of mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease and preserves cognitive function. The mechanism involves recruiting brain cells known as astrocytes, star shaped cells in the brain, to remove the toxic amyloid plaques that build up in many Alzheimer’s disease brains. Increasing the production of Sox9, a key protein that regulates astrocyte functions during aging, triggered the astrocytes’ ability to remove amyloid plaques. The study, published in Nature Neuroscience, suggests a potential astrocyte-based therapeutic approach to ameliorate cognitive decline in neurodegenerative disease.

“Astrocytes perform diverse tasks that are essential for normal brain function, including facilitating brain communications and memory storage. As the brain ages, astrocytes show profound functional alterations; however, the role these alterations play in aging and neurodegeneration is not yet understood,” said first author Dr. Dong-Joo Choi, who was at the Center for Cell and Gene Therapy and the Department of Neurosurgery at Baylor while he was working on this project. Choi currently is an assistant professor at the Center for Neuroimmunology and Glial Biology, Institute of Molecular Medicine at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston.

Astrocytic Sox9 overexpression in Alzheimer’s disease mouse models promotes Aβ plaque phagocytosis and preserves cognitive function.

The human body depends on accurate genetic instructions to keep its cells working properly. Cancer begins to form when these instructions become disrupted. As genetic mistakes build up over time, cells can lose their normal limits on growth and start multiplying in an uncontrolled way. Chromosomal abnormalities – numerical and structural defects in chromosomes – are often one of the earliest changes that push healthy cells toward becoming cancerous.

Researchers in the Korbel Group at EMBL Heidelberg have created a new AI-based tool that gives scientists a way to closely examine how these chromosomal abnormalities develop. The insights gained from this approach may eventually clarify some of the earliest steps that lead to cancer.

“Chromosomal abnormalities are a main driver for particularly aggressive cancers, and they’re highly linked to patient death, metastasis, recurrence, chemotherapy resistance, and fast tumor onset,” said Jan Korbel, senior scientist at EMBL and senior author of the new paper, published in the journal Nature. “We wanted to understand what determines the likelihood that cells undergo such chromosomal alterations, and what’s the rate at which such abnormalities arise when a still normal cell divides.”

Integrated genomic and transcriptomic profiling of glioblastoma reveals ecDNA-driven heterogeneity and microenvironmental reprogramming.

Tang et al. provide a comprehensive genomic and transcriptomic characterization of extrachromosomal DNA (ecDNA) in glioblastoma. They reveal that EGFR ecDNA shapes transcriptional subtypes and reprograms the tumor microenvironment by stabilizing metabolically active tumor-associated macrophages. These findings uncover mechanistic links between ecDNA architecture and glioblastoma progression, highlighting potential therapeutic vulnerabilities.

On Mars, winds constantly stir up whirlwinds of fine dust. It was at the center of two of these dust devils that the SuperCam instrument’s microphone, the first ever to operate on Mars, accidentally recorded particularly strong signals.

Analyses carried out by scientists at the Institut de recherche en astrophysique et planétologie (CNES/CNRS/Université de Toulouse) and the laboratoire Atmosphères et observations spatiales (CNRS/Sorbonne Université/Université de Versailles Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines) showed that they were the electromagnetic and acoustic signatures of electric discharges comparable to the small static electricity shocks that can be experienced on Earth when touching a door handle in dry weather. Long theorized, the existence of electric discharges in the Martian atmosphere has now been confirmed by observation for the first time.

The findings are published in the journal Nature.

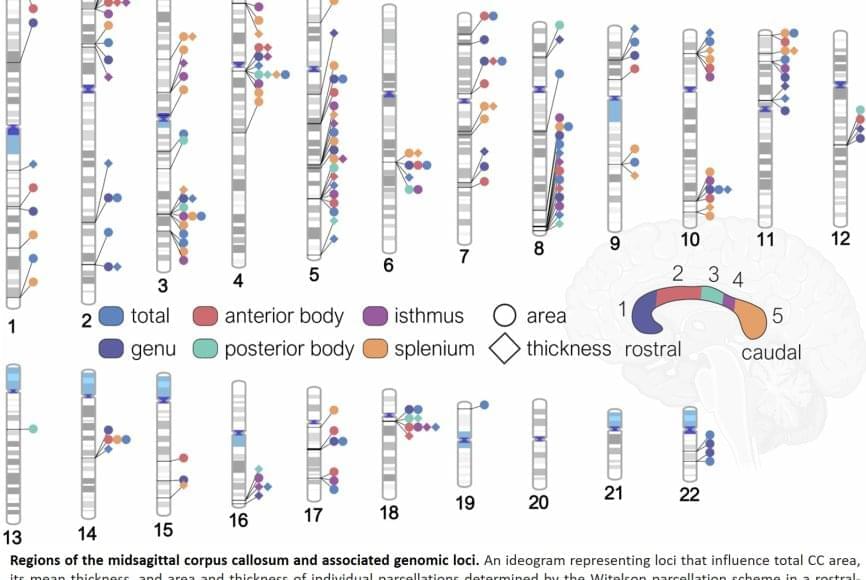

The corpus callosum is critical for nearly everything the brain does, from coordinating the movement of our limbs in sync to integrating sights and sounds, to higher-order thinking and decision-making. Abnormalities in its shape and size have long been linked to disorders such as ADHD, bipolar disorder, and Parkinson’s disease. Until now, the genetic underpinnings of this vital structure remained largely unknown.

In the new study, published in Nature Communications, the team analyzed brain scans and genetic data from over 50,000 people, ranging from childhood to late adulthood, with the help of a new tool the team created that leverages artificial intelligence.

“We developed an AI tool that finds the corpus callosum in different types of brain MRI scans and automatically takes its measurements,” said co-first author of the study. Using this tool, the researchers identified dozens of genetic regions that influence the size and thickness of the corpus callosum and its subregions.

The study revealed that different sets of genes govern the area versus the thickness of the corpus callosum—two features that change across the lifespan and play distinct roles in brain function. Several of the implicated genes are active during prenatal brain development, particularly in processes like cell growth, programmed cell death, and the wiring of nerve fibers across hemispheres.

Notably, the study found genetic overlap between the corpus callosum and the cerebral cortex—the outer layer of the brain responsible for memory, attention, and language—as well as with conditions such as ADHD and bipolar disorder.

For the first time, a research team has mapped the genetic architecture of a crucial part of the human brain known as the corpus callosum—the thick band of nerve fibers that connects the brain’s left and right hemispheres. The findings open new pathways for discoveries about mental illness, neurological disorders and other diseases related to defects in this part of the brain.