A Hegemonizing Swarm is a hypothetical living weapon, or self-replicating machine, which seeks to turn every last available bit of matter into more of itself…

Get the latest international news and world events from around the world.

Researchers use quantum computer to identify molecular candidate for development of more efficient solar cells

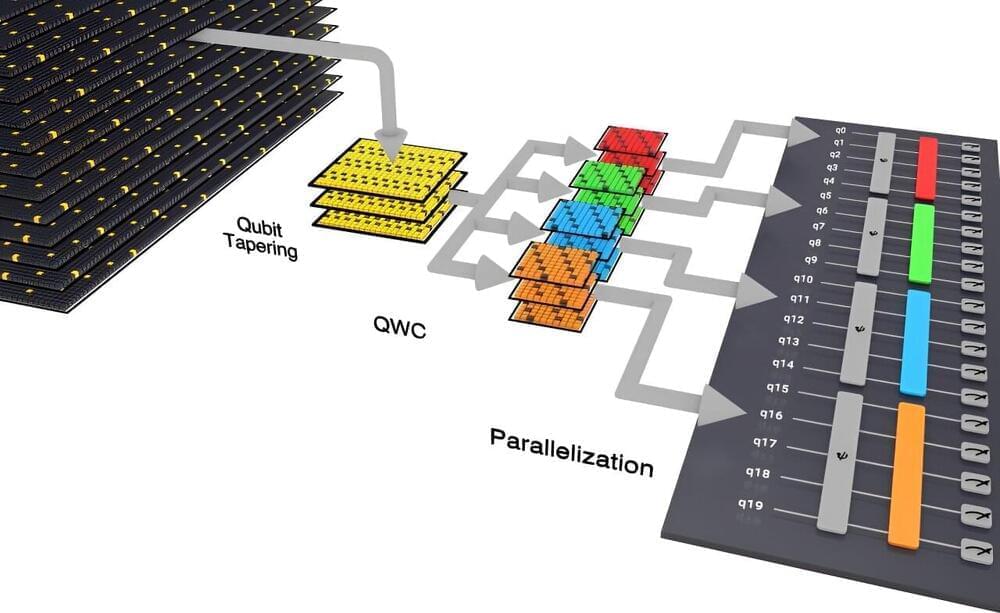

Using the full capabilities of the Quantinuum H1-1 quantum computer, researchers from the Department of Energy’s Oak Ridge National Laboratory not only demonstrated best practices for scientific computing on current quantum systems but also produced an intriguing scientific result.

By modeling singlet fission —in which absorption of a single photon of light by a molecule produces two excited states —the team confirmed that the linear H4 molecule’s energetic levels match the fission process’s requirements. The linear H4 molecule is, simply, a molecule made of four hydrogen atoms arranged in a linear fashion.

A molecule’s energetic levels are the energies of each quantum state involved in a phenomenon, such as singlet fission, and how they relate and compare with one another. The fact that the linear molecule’s energetic levels are conducive to singlet fission could prove to be useful knowledge in the overall effort to develop more efficient solar panels.

Blue Alchemist to make solar cells on the Moon using moondust

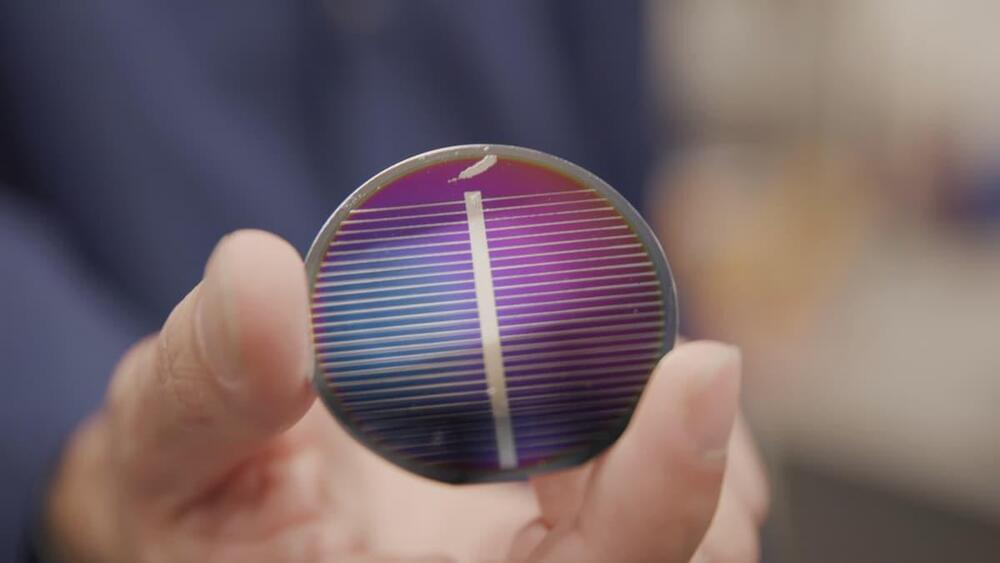

With the aim of allowing astronauts to live off the land as much as possible when they return to the Moon, NASA has awarded Blue Origin a US$35-million Tipping Point contract to develop the company’s Blue Alchemist process to make solar cells out of lunar soil.

The biggest bottleneck to establishing a permanent human presence on the Moon and beyond is the staggering cost of sending equipment and supplies from Earth. NASA and other space agencies believe that the best way to overcome this is to use local resources as much as possible to manufacture what’s needed.

Under development since 2021, Blue Alchemist is an example of this. The basic concept is to develop a complete process that takes the lunar soil, more formally known as the regolith, at one end and spits out complete solar cells and other products at the other.

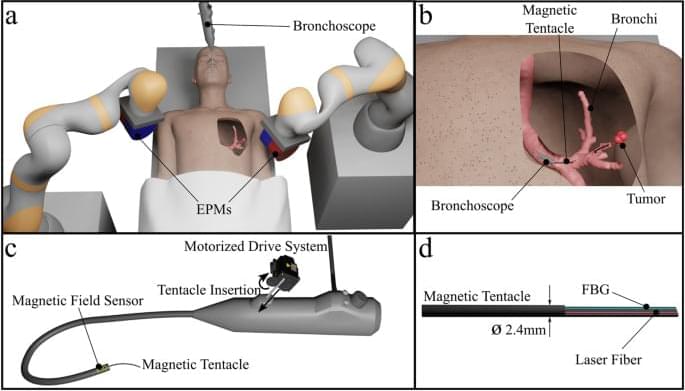

Personalized magnetic tentacles for targeted photothermal cancer therapy in peripheral lungs

All navigations reported in Fig. 2 were performed autonomously within 150 s and without intraoperative imaging. Specifically, each navigation was performed according to the pre-determined optimal actuation fields and supervised in real time by intraoperative localization. Therefore, the set of complex navigations performed by the magnetic tentacle was possible without the need for exposure to radiation-based imaging. In all cases, the soft magnetic tentacle is shown to conform by design to the anatomy thanks to its low stiffness, optimal magnetization profile and full-shape control. Compared to a stiff catheter, the non-disruptive navigation achieved by the magnetic tentacle can improve the reliability of registration with pre-operative imaging to enhance both navigation and targeting. Moreover, compared to using multiple catheters with different pre-bent tips, the optimization approach used for the magnetic tentacle design determines a single magnetization profile specific to the patient’s anatomy that can navigate the full range of possible pathways illustrated in Fig. 2. Supplementary Movies S1 and S2 report all the experiments. Supplementary Movie S1 shows the online tracking capabilities of the proposed platform.

In Table 1, we report the results of the localization for four different scenarios. These cases highlight diverse navigations in the left and right bronchi. The error is referred to as the percentage of tentacles outside the anatomy. This was computed by intersecting the shape of the catheter, as predicted by the FBG sensor, and the anatomical mesh grid extracted from the CT scan. The portion of the tentacle within the anatomy was measured by using “inpolyhedron” function in MATLAB. In Supplementary Movie S1, this is highlighted in blue, while the section of the tentacle outside the anatomy is marked in red. The error in Table 1 was computed using the equation.

Brain stimulation for treatment and enhancement in children: an ethical analysis

Davis (2014) called for “extreme caution” in the use of non-invasive brain stimulation (NIBS) to treat neurological disorders in children, due to gaps in scientific knowledge. We are sympathetic to his position. However, we must also address the ethical implications of applying this technology to minors. Compensatory trade-offs associated with NIBS present a challenge to its use in children, insofar as these trade-offs have the effect of limiting the child’s future options. The distinction between treatment and enhancement has some normative force here. As the intervention moves away from being a treatment toward being an enhancement—and thus toward a more uncertain weighing of the benefits, risks, and costs—considerations of the child’s best interests (as judged by the parents) diminish, and the need to protect the child’s (future) autonomy looms larger. NIBS for enhancement involving trade-offs should therefore be delayed, if possible, until the child reaches a state of maturity and can make an informed, personal decision. NIBS for treatment, by contrast, is permissible insofar as it can be shown to be at least as safe and effective as currently approved treatments, which are (themselves) justified on a best interests standard.

See Full PDF

“We’re All Asgardians”: Scientists Discover New Clues About the Origin of Complex Life

The mythological Norse god Thor hails from the celestial city of Asgard, and according to revolutionary research published in the scientific journal, Nature, he’s not the only Asgardian. This new research suggests that we humans — along with eagles, starfish, daisies, and every complex organism on Earth — are, in a sense, Asgardians.

The research team at The University of Texas at Austin, along with collaborators from different institutions, conducted a genomic analysis of several hundreds of microorganisms known as archaea. Their findings revealed that eukaryotes – complex life forms with nuclei in their cells, including all flora, fauna, insects, and fungi across the globe – can trace their origins back to a common Asgard archaean ancestor.

That means eukaryotes are, in the parlance of evolutionary biologists, a “well-nested clade” within Asgard archaea, similar to how birds are one of several groups within a larger group called dinosaurs, sharing a common ancestor. The team has found that all eukaryotes share a common ancestor among the Asgards.

Scientists might have made the ‘biggest physics discovery of a lifetime’ — or not

Scientists have claimed to make a breakthrough that would be “one of the holy grails of modern physics” – but experts have urged caution about the results.

In recent days, many commentators have become excited by two papers that claim to document the production of a new superconductor that works at room temperature and ambient pressure. Scientists in Korea said they had synthesised a new material called LK-99 that would represent one of the biggest physics breakthroughs of recent decades.

Superconductors are a special kind of material where electrical resistance vanishes, and which throw out magnetic fields. They are widely useful, including in the production of powerful magnets and in reducing the amount of energy lost as it moves through circuits.

A butterfly’s first flight inspires a new way to produce force and electricity

The wings of a butterfly are made of chitin, an organic polymer that is the main component of the shells of arthropods like crustaceans and other insects. As a butterfly emerges from its cocoon in the final stage of metamorphosis, it will slowly unfold its wings into their full grandeur.

During the unfolding, the chitinous material becomes dehydrated while blood pumps through the veins of the butterfly, producing forces that reorganize the molecules of the material to provide the unique strength and stiffness necessary for flight. This natural combination of forces, movement of water, and molecular organization is the inspiration behind Associate Professor Javier G. Fernandez’s research.

Alongside fellow researchers from the Singapore University of Technology and Design (SUTD), Fernandez has been exploring the use of chitinous polymers as a sustainable material for engineering applications.

The #1 way to strengthen your mind is to use your body | Wendy Suzuki

Exercise gives your brain a “bubble bath of neurochemicals,” says Wendy Suzuki, a professor of neural science.

Up next, Forensic accountant explains why fraud thrives on Wall Street.

► https://youtu.be/GHKyDYtKGEg.

Exercise can have surprisingly transformative impacts on the brain, according neuroscientist Wendy Suzuki. It has the power not only to boost mood and focus due to the increase in neurotransmitters like dopamine, serotonin, and noradrenaline, but also contributes to long-term brain health. Exercise stimulates the growth of new brain cells, particularly in the hippocampus, improving long-term memory and increasing its volume. Suzuki notes that you don’t have to become a marathon runner to obtain these benefits — even just 10 minutes of walking per day can have noticeable benefits. It just takes a bit of willpower and experimentation.

0:00 My exercise epiphany.

1:35 What is “runner’s high”?

2:40 The hippocampus & prefrontal cortex.

3:32 Neuroplasticity: It’s never too late to move your body.

Read the video transcript ► https://bigthink.com/series/the-big-think-interview/how-the-…escription.

About Wendy Suzuki:

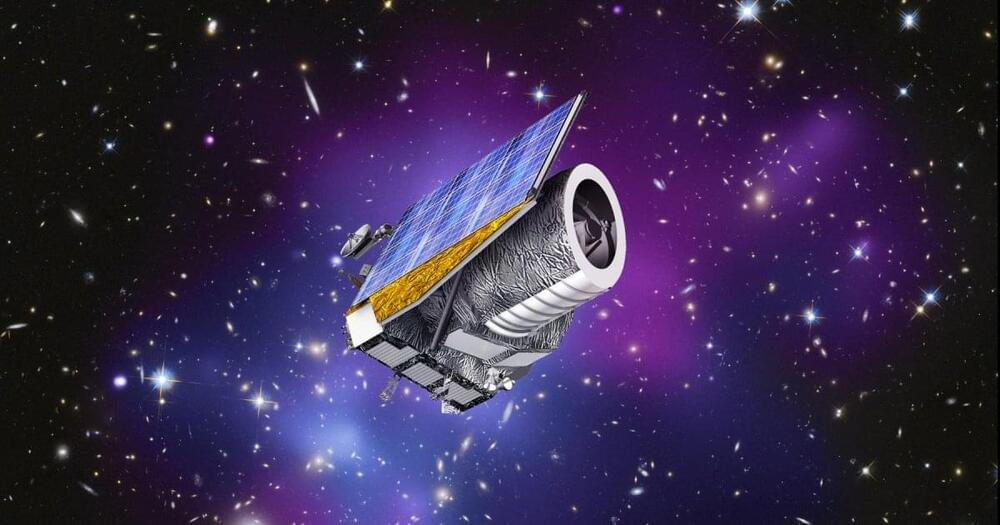

The hunt for dark matter is further along than you think

Dark matter isn’t just floating around filling up empty space. Importantly, it is found in clumps and structures, similar to ordinary matter. It forms the structure onto which ordinary matter gloms and is thought to be responsible for the structures of galaxies and the universe as a whole.

“We know that galaxies form in the scaffold that dark matter produces,” astronomer and early universe researcher Steve Wilkins of the University of Sussex explained. “It is an integral part of our universe to explain what we see.”

“We don’t have a firm theoretical handle on what dark matter should be.”