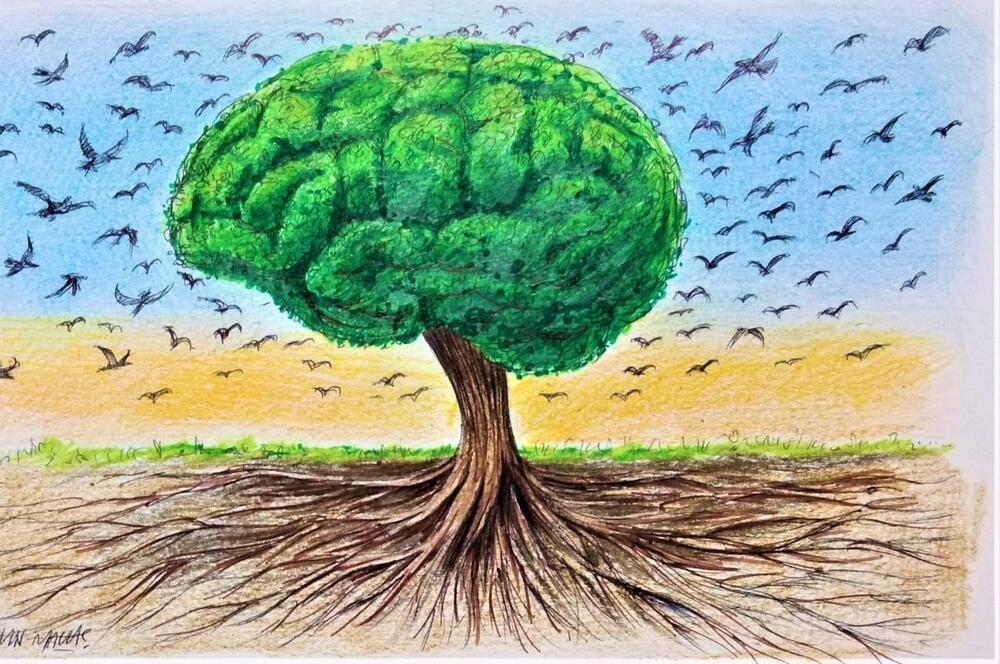

Rene Descartes, the father of cartesian philosophy, puts forward the relationship between sciences and especially the relation of metaphysics with other sciences through a metaphor known as the “Tree of Knowledge.” He describes knowledge as a tree and sciences are connected with each other as if they are parts of a tree. Its trunk is physics, its branches are other sciences and the fruit, which is considered to be the goal of a tree, is the science of morals. We are familiar with this metaphor and its varieties in philosophy and Sufism. In particular, it is a common metaphor to accept morals as “the fruit.” Morals, which are the intent of scientific activity, are deemed worthy of being the fruit, or the goal, by many thinkers. As a matter of fact, Ibn Arabi and Qunawi also used the same metaphor. They categorized the science of morals that is often identified with Sufism as the fruit of a tree and the goal of all human endeavors. Descartes completes his metaphor by saying that the tree’s roots are metaphysics. It is the roots that sustain a tree; the trunk, branches and fruits all depend on roots and are nourished by them, which makes the roots the most indispensable part. In this respect, this metaphor can be interpreted as a tribute to metaphysics.

While the tree of knowledge designates the place metaphysics holds among sciences, it seems to correspond with classical metaphysics, at least formally. Because the principal and subsidiary divisions of science (root and branch) are used by classical metaphysics to explain the relation of metaphysics with other sciences, the concepts of “principle and subsidiary” can be replaced by “universal and divisive,” and the meaning will not change: Metaphysics is a universal science and all other sciences serve to it as its particulars. It separates from other sciences, which examine the being from a specific angle, as metaphysics examines being qua being. Its superiority comes from this unique field of research. Because of its superior status, metaphysics is entrusted with another duty: Universal science is the most fundamental field as it certifies the principles of other sciences. The most controversial part of this assertion is whether such a superior science is possible and, if so, what method it has to attain knowledge. We will get to that, but now it is enough to state that: Despite the formal similarities, it is unlikely that Descartes could form a metaphysical understanding through this metaphor in the classical sense.