A network that connects quantum devices and a central server that spans Hefei, China, can allow multiple secure quantum chats at once.

A network that connects quantum devices and a central server that spans Hefei, China, can allow multiple secure quantum chats at once.

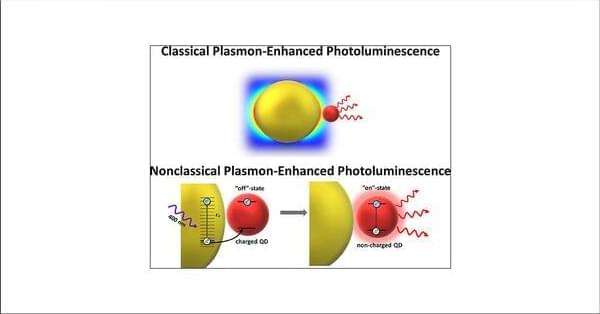

Metal-enhanced photoluminescence is able to provide a robust signal even from a single emitter and is promising in applications in biosensors and optoelectronic devices. However, its realization with semiconductor nanocrystals (e.g., quantum dots, QDs) is not always straightforward due to the hidden and not fully described interactions between plasmonic nanoparticles and an emitter. Here, we demonstrate nonclassical enhancement (i.e., not a conventional electromagnetic mechanism) of the QD photoluminescence at nonplasmonic conditions and correlate it with the charge exchange processes in the system, particularly with high efficiency of the hot-hole generation in gold nanoparticles and the possibility of their transfer to QDs.

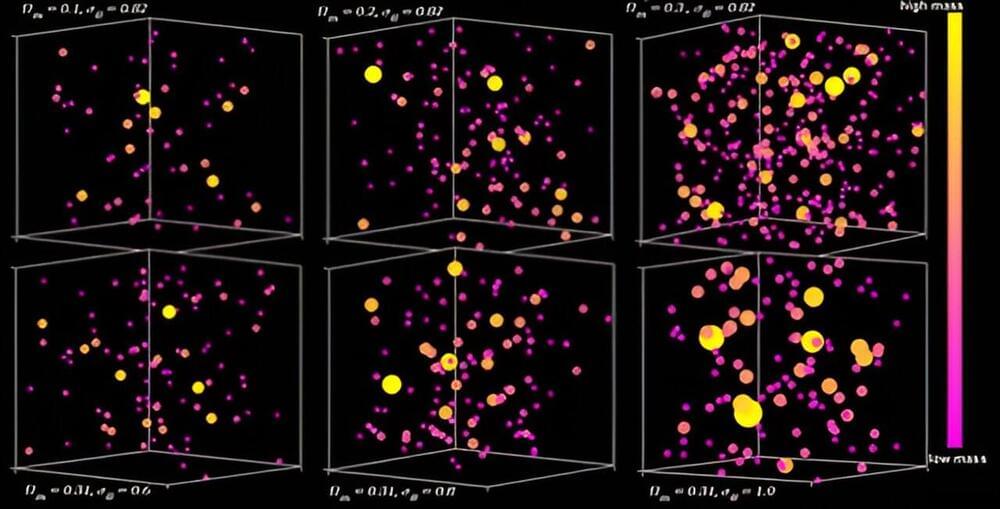

One of the most interesting and important questions in cosmology is, “How much matter exists in the universe?” An international team, including scientists at Chiba University, has now succeeded in measuring the total amount of matter for the second time. Reporting in The Astrophysical Journal, the team determined that matter makes up 31% of the total amount of matter and energy in the universe, with the remainder consisting of dark energy.

“Cosmologists believe that only about 20% of the total matter is made of regular or ‘baryonic’ matter, which includes stars, galaxies, atoms, and life,” explains first author Dr. Mohamed Abdullah, a researcher at the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics-Egypt, Chiba University, Japan. “About 80% is made of dark matter, whose mysterious nature is not yet known but may consist of some as-yet-undiscovered subatomic particles.”

“The team used a well-proven technique to determine the total amount of matter in the universe, which is to compare the observed number and mass of galaxy clusters per unit volume with predictions from numerical simulations,” says co-author Gillian Wilson, Abdullah’s former graduate advisor and Professor of Physics and Vice Chancellor for research, innovation, and economic development at UC Merced.

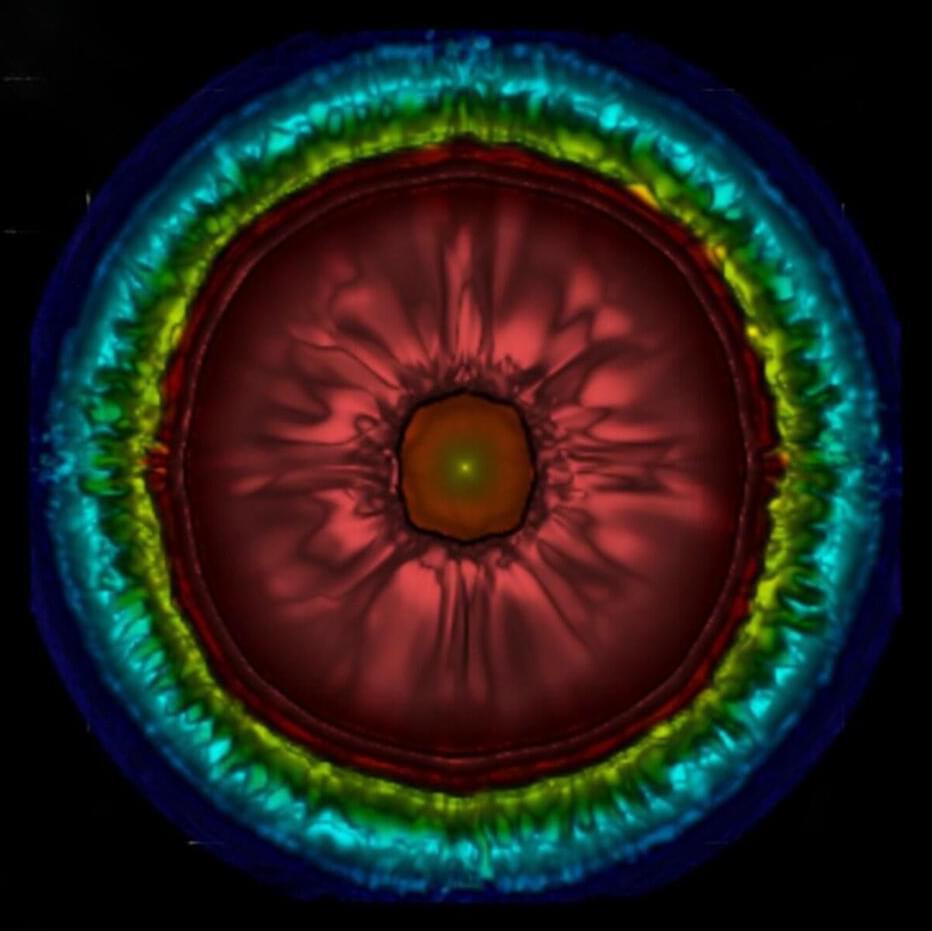

After years of dedicated research and over 5 million supercomputer computing hours, a team has created the world’s first high-resolution 3D radiation hydrodynamics simulations for exotic supernovae. This work is reported in The Astrophysical Journal.

Ke-Jung Chen at Academia Sinica Institute of Astronomy and Astrophysics (ASIAA) in Taiwan, led an international team and used the powerful supercomputers from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan to make the breakthrough.

Supernova explosions are the most spectacular endings for massive stars, as they conclude their life cycles in a self-destructive manner, instantaneously releasing brightness equivalent to billions of suns, illuminating the entire universe.

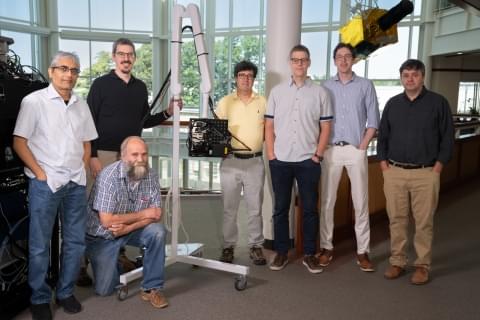

🏅 R&D 100 Award Winner 🏅

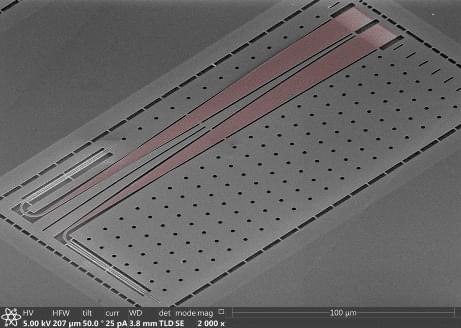

The Noncontact Laser Ultrasound (NCLUS) is a portable laser-based system that acquires ultrasound images of human tissue without touching a patient. It offers capabilities comparable to those of an MRI and CT but at vastly lower cost in an automated and portable platform.

In addition to receiving an R&D 100 Award, NCLUS received the Silver Medal in the Special Recognition: Market Disruptor Products category. Congratulations to the NCLUS team!

Researchers from MIT Lincoln Laboratory and their collaborators at the Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) Center for Ultrasound Research and Translation (CURT) have developed a new medical imaging device: the Noncontact Laser Ultrasound (NCLUS). This laser-based ultrasound system provides images of interior body features such as organs, fat, muscle, tendons, and blood vessels. The system also measures bone strength and may have the potential to track disease stages over time.

“Our patented skin-safe laser system concept seeks to transform medical ultrasound by overcoming the limitations associated with traditional contact probes,” explains principal investigator Robert Haupt, a senior staff member in Lincoln Laboratory’s Active Optical Systems Group. Haupt and senior staff member Charles Wynn are co-inventors of the technology, with assistant group leader Matthew Stowe providing technical leadership and oversight of the NCLUS program. Rajan Gurjar is the system integrator lead, with Jamie Shaw, Bert Green, Brian Boitnott (now at Stanford University), and Jake Jacobsen collaborating on optical and mechanical engineering and construction of the system.

Medical ultrasound in practice

Apple unveiled its new iPhone lineup on Tuesday, with its Lightning charger ports replaced on the newest models by a universal charger after a tussle with the European Union.

The European bloc is insisting that all phones and other small devices must be compatible with the USB-C charging cables from the end of next year, a move it says will reduce waste and save money for consumers.

The firm had long argued that its cable was more secure than USB-C chargers, which are already deployed by Apple on other devices and widely used by rivals including the world’s biggest smartphone maker Samsung.