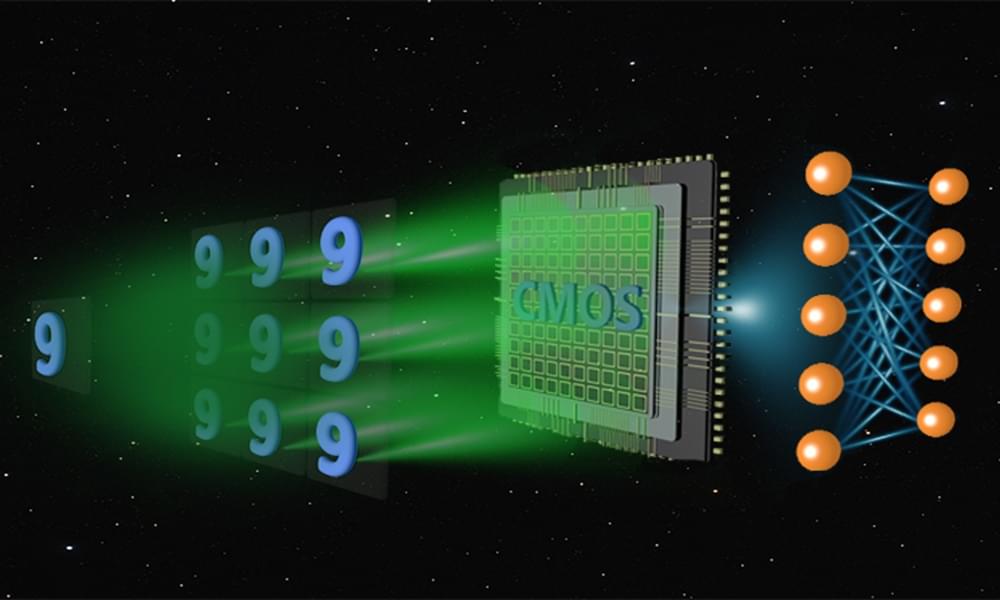

Quantum computers have the potential to revolutionize computing by solving complex problems that stump even today’s fastest machines. Scientists are exploring whether quantum computers could one day help streamline global supply chains, create ultra-secure encryption to protect sensitive data against even the most powerful cyberattacks, or even develop more effective drugs by simulating their behavior at the atomic level.

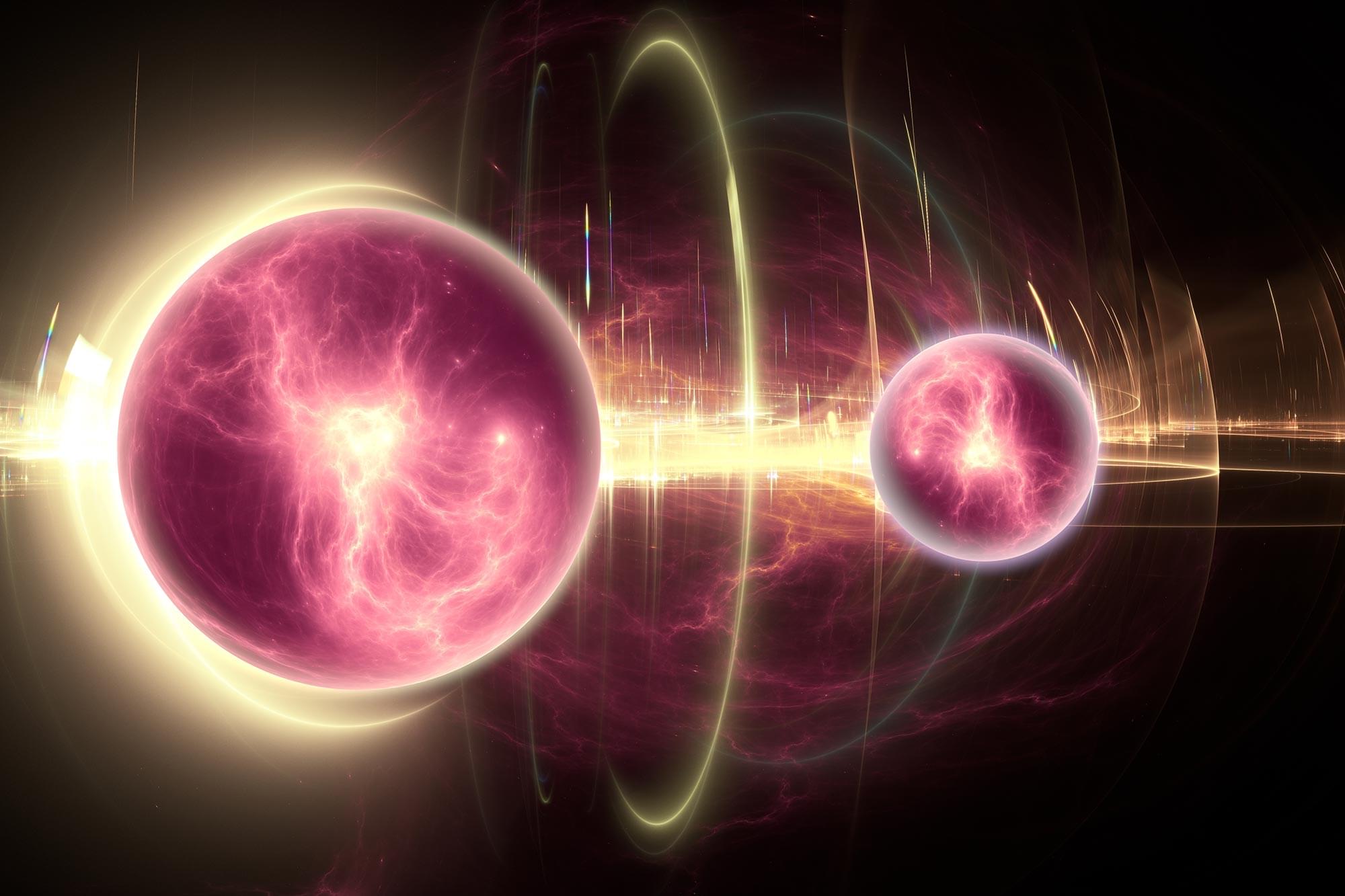

But building efficient quantum computers isn’t just about developing faster chips or better hardware. It also requires a deep understanding of quantum mechanics—the strange rules that govern the tiniest building blocks of our universe, such as atoms and electrons—and how to effectively move information through quantum systems.

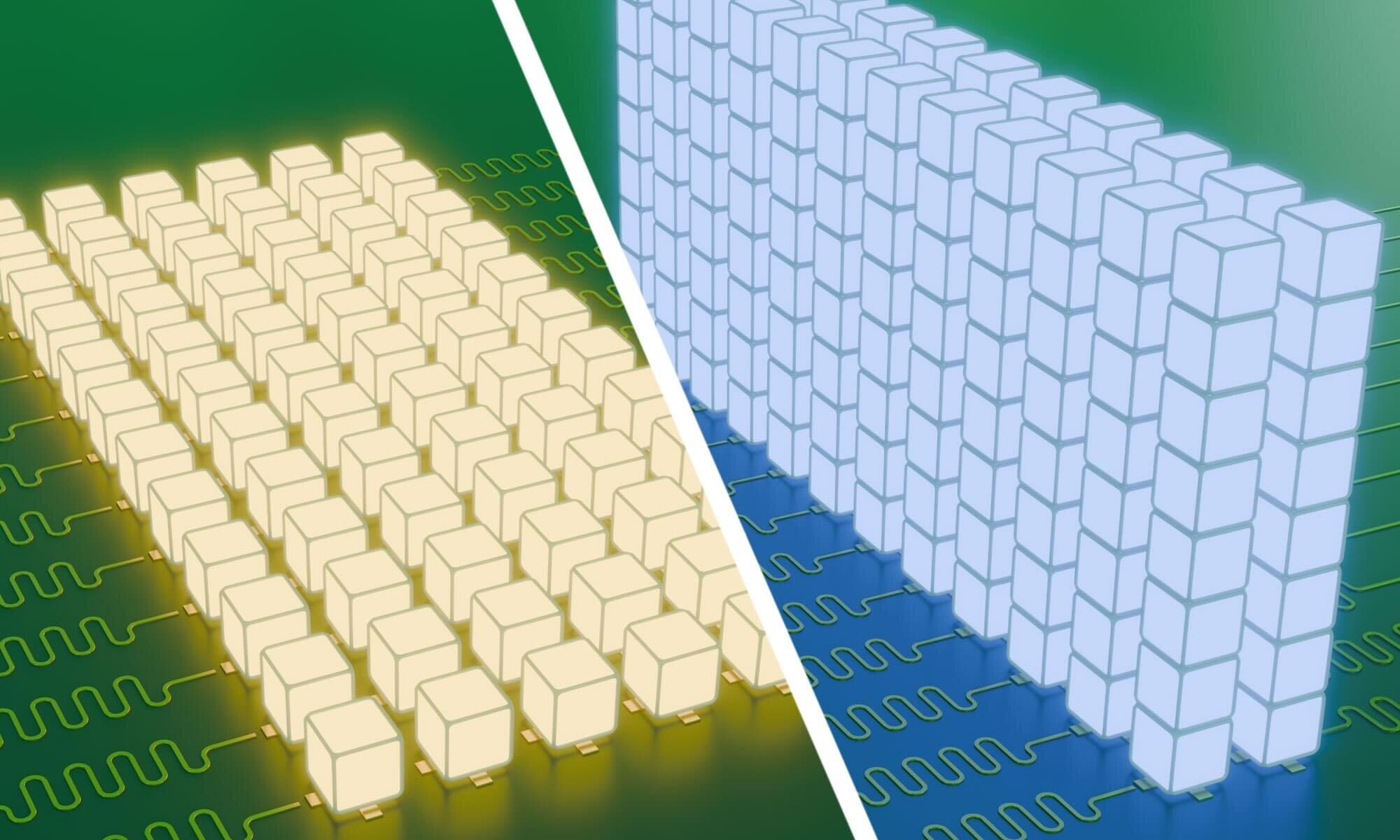

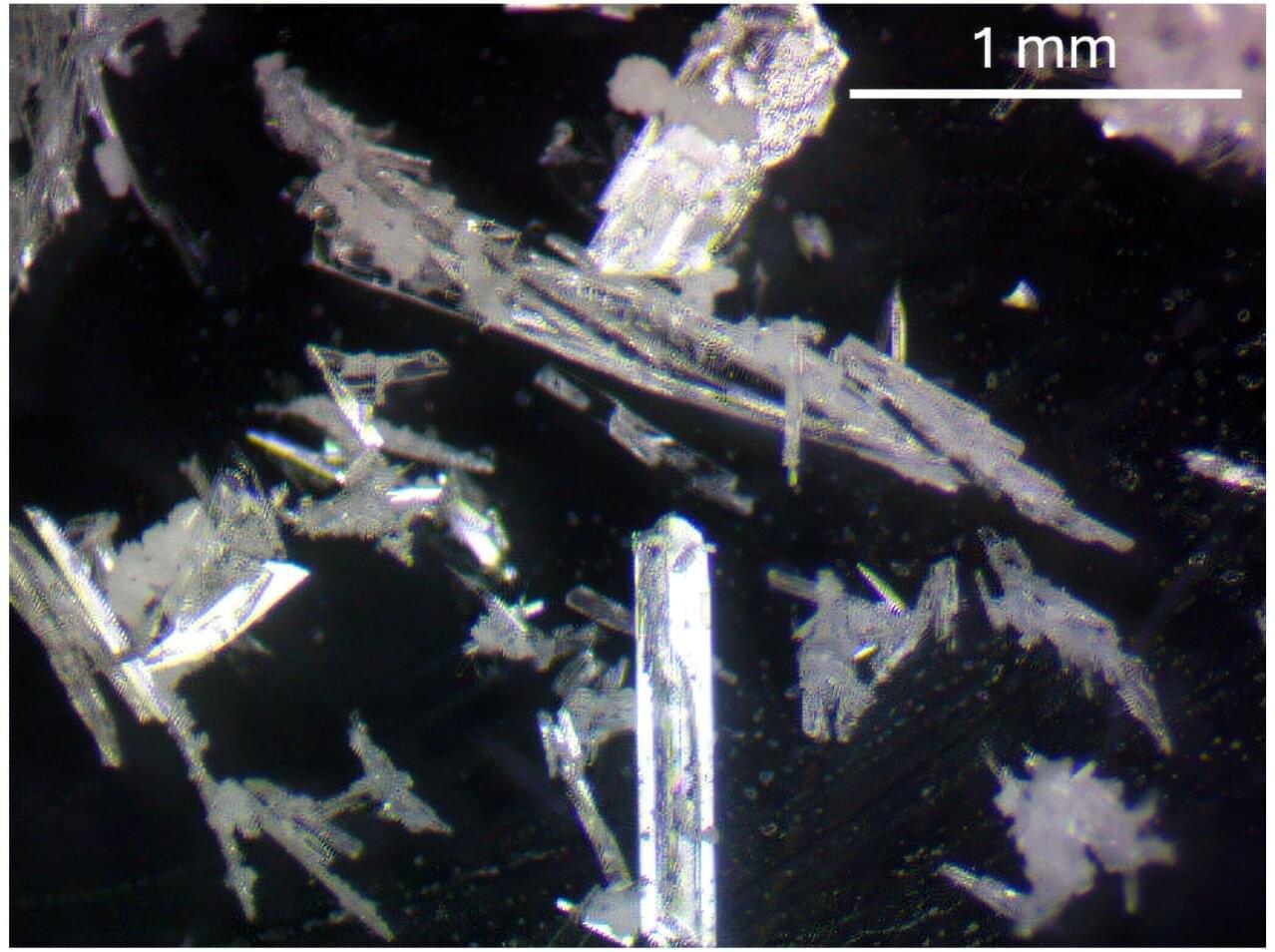

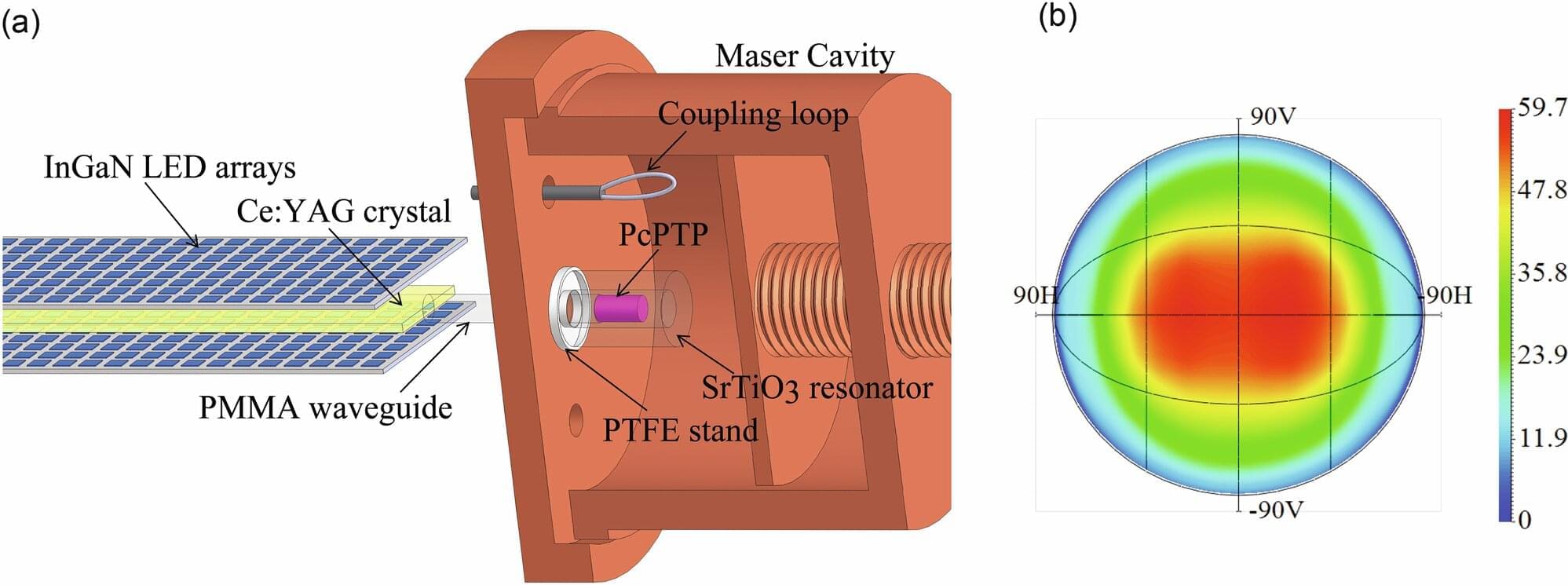

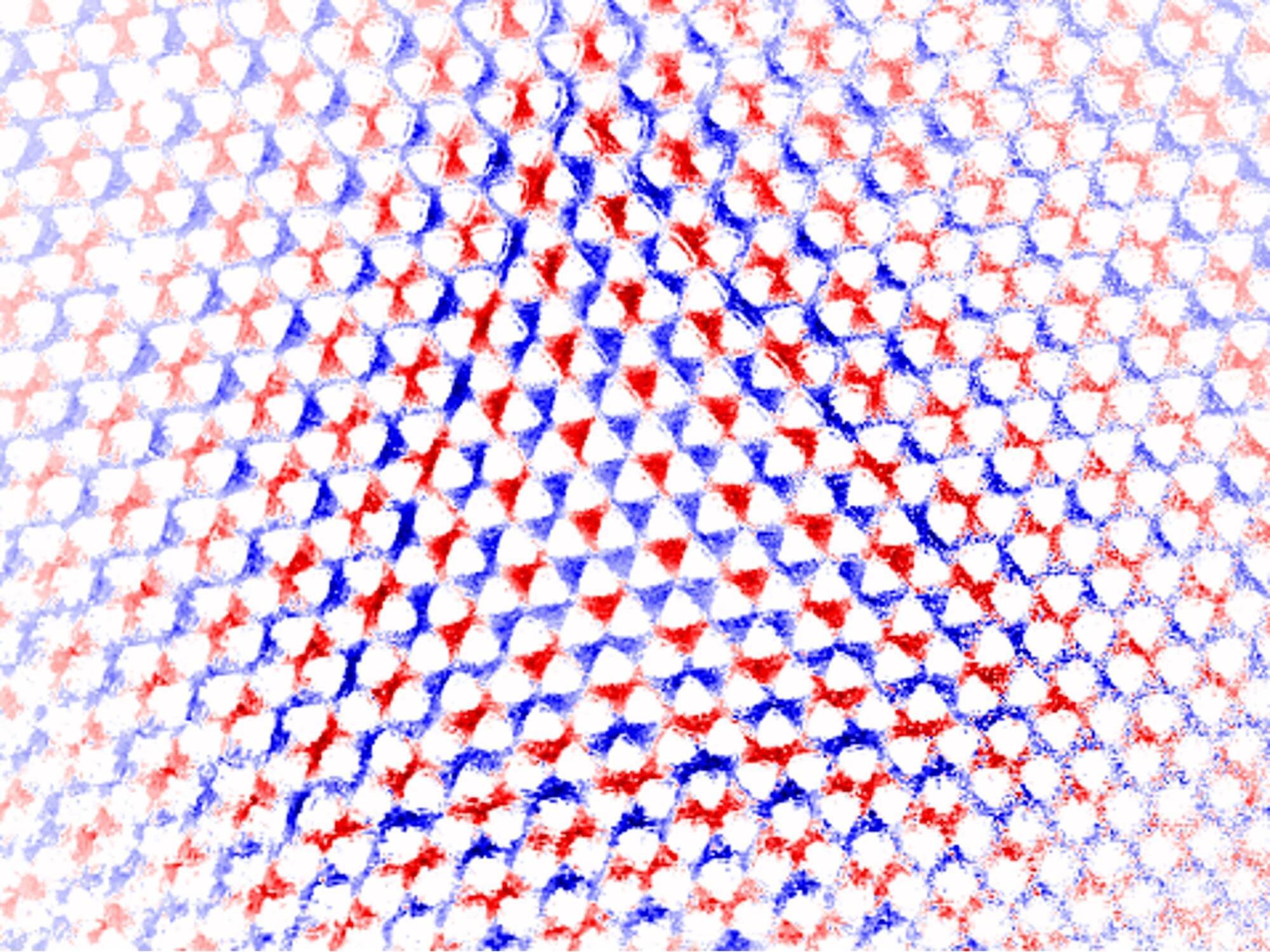

In a paper published in Physics Review X, a team of physicists—including graduate student Elizabeth Champion and assistant professor Machiel Blok from the University of Rochester’s Department of Physics and Astronomy—outlined a method to address a tricky problem in quantum computing: how to efficiently move information within a multi-level system using quantum units called qudits.