A new breakthrough shows how robots can now integrate both sight and touch to handle objects with greater accuracy, similar to humans.

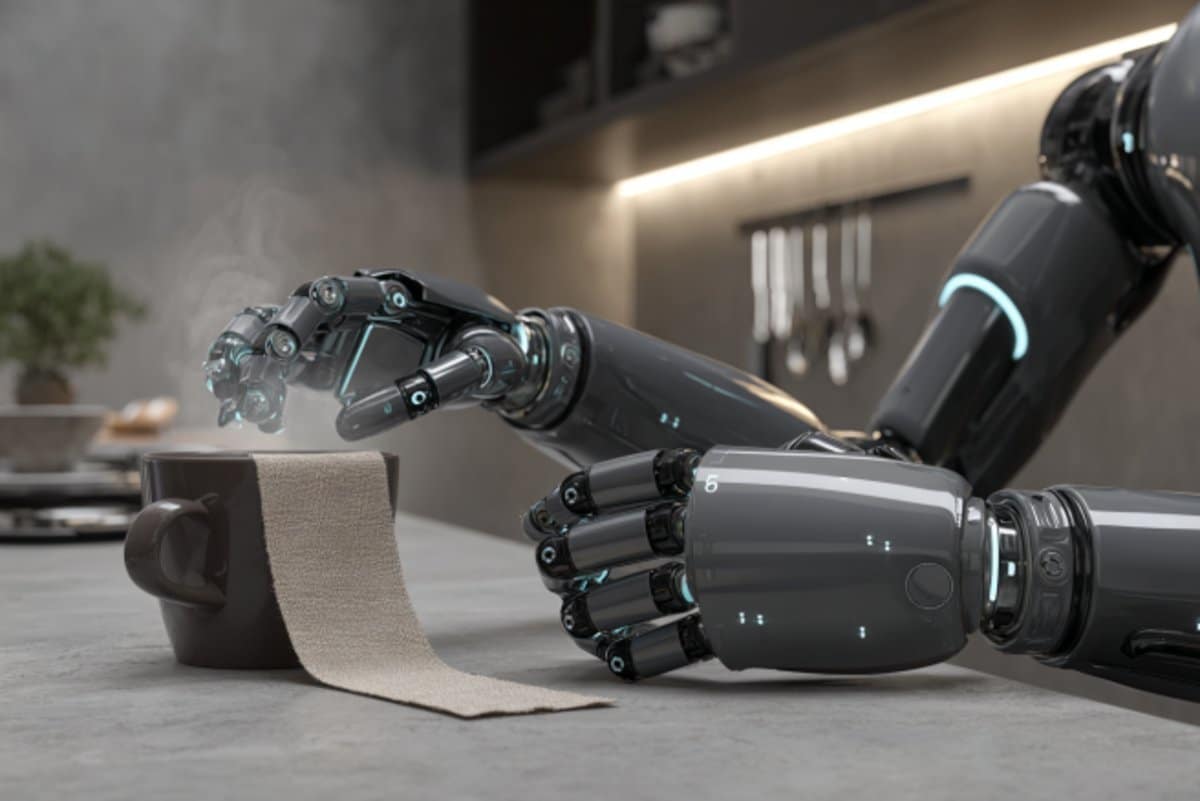

Lipid molecules, or fats, are crucial to all forms of life. Cells need lipids to build membranes, separate and organize biochemical reactions, store energy, and transmit information. Every cell can create thousands of different lipids, and when they are out of balance, metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases can arise. It is still not well understood how cells sort different types of lipids between cell organelles to maintain the composition of each membrane. A major reason is that lipids are difficult to study, since microscopy techniques to precisely trace their location inside cells have so far been missing.

The researchers developed a method that enables visualizing lipids in cells using standard fluorescence microscopy. After the first successful proof of concept, the authors brought mass-spectrometry expert on board to study how lipids are transported between cellular organelles.

“We started our project with synthesizing a set of minimally modified lipids that represent the main lipids present in organelle membranes. These modified lipids are essentially the same as their native counterparts, with just a few different atoms that allowed us to track them under the microscope,” explains a PhD student in the group.

The modified lipids mimic natural lipids and are “bifunctional,” which means they can be activated by UV light, causing the lipid to bind or crosslink with nearby proteins. The modified lipids were loaded in the membrane of living cells and, over time, transported into the membranes of organelles. The researchers worked with human cells in cell culture, such as bone or intestinal cells, as they are ideal for imaging.

“After the treatment with UV light, we were able to monitor the lipids with fluorescence microscopy and capture their location over time. This gave us a comprehensive picture of lipid exchange between cell membrane and organelle membranes,” concludes the author.

In order to understand the microscopy data, the team needed a custom image analysis pipeline. “To address our specific needs, I developed an image analysis pipeline with automated image segmentation assisted by artificial intelligence to quantify the lipid flow through the cellular organelle system,” says another author.

By combining the image analysis with mathematical modeling, the research team discovered that between 85% and 95% of the lipid transport between the membranes of cell organelles is organized by carrier proteins that move the lipids, rather than by vesicles. This non-vesicular transport is much more specific with regard to individual lipid species and their sorting to the different organelles in the cell. The researchers also found that the lipid transport by proteins is ten times faster than by vesicles. These results imply that the lipid compositions of organelle membranes are primarily maintained through fast, species-specific, non-vesicular lipid transport.

Scientists at the University of Pennsylvania have shown for the first time that it’s possible to detect dormant cancer cells in breast cancer survivors and eliminate them with repurposed drugs, potentially preventing recurrence. In a clinical trial, existing medications cleared these hidden cells in most participants, leading to survival rates above 90%. The findings open a new era of proactive treatment against breast cancer’s lingering threat, offering hope to survivors haunted by the fear of relapse.

Imagine a clock that doesn’t have electricity, but its hands and gears spin on their own for all eternity. In a new study, physicists at the University of Colorado Boulder have used liquid crystals, the same materials that are in your phone display, to create such a clock—or, at least, as close as humans can get to that idea. The team’s advancement is a new example of a “time crystal.” That’s the name for a curious phase of matter in which the pieces, such as atoms or other particles, exist in constant motion.

The researchers aren’t the first to make a time crystal, but their creation is the first that humans can actually see, which could open a host of technological applications.

“They can be observed directly under a microscope and even, under special conditions, by the naked eye,” said Hanqing Zhao, lead author of the study and a graduate student in the Department of Physics at CU Boulder.

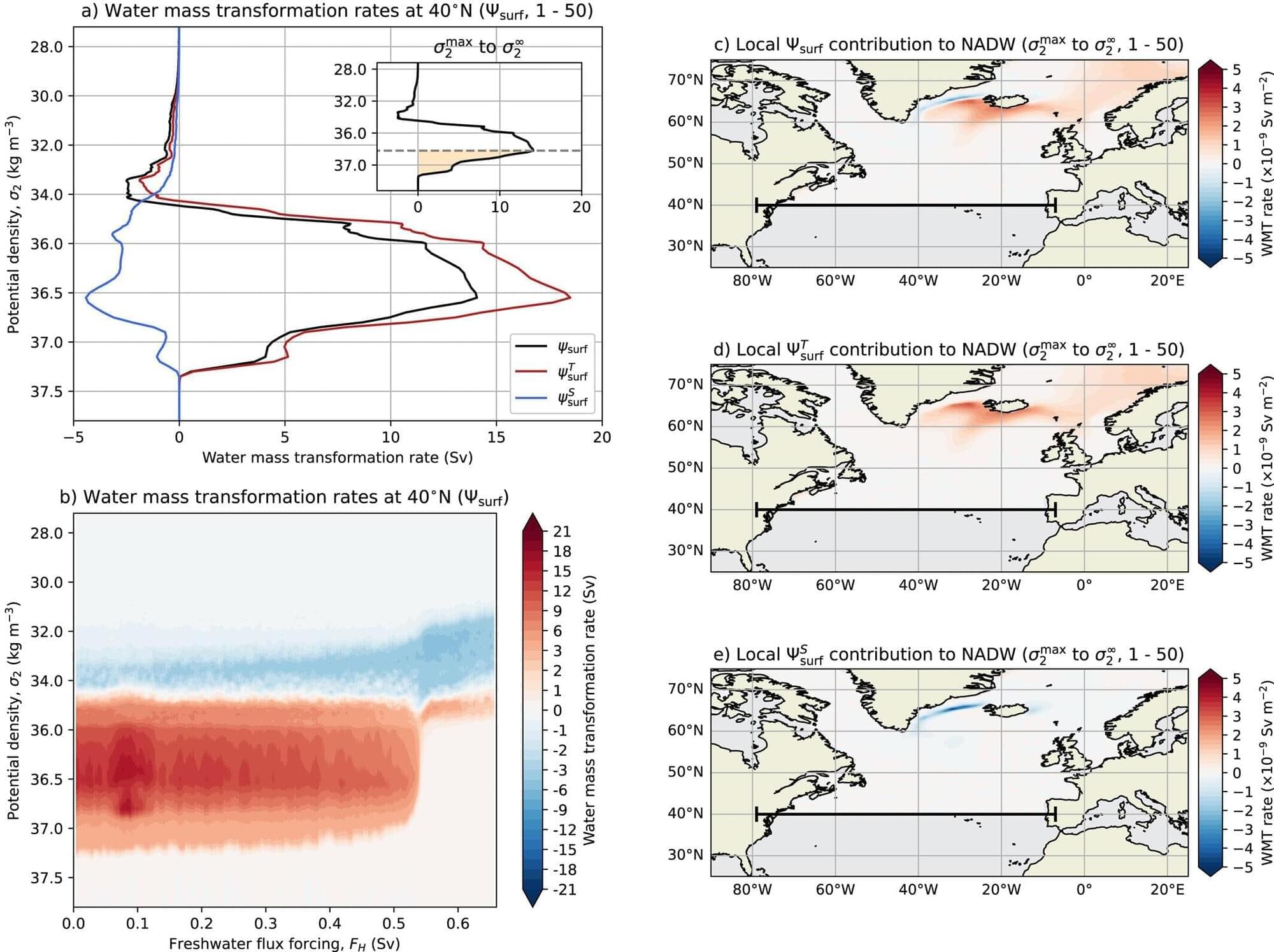

The Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) is an enormous loop of ocean current in the Atlantic Ocean that carries warmer waters north and colder waters south, helping to regulate the climate in many regions. The collapse of this critical circulation system has the potential to cause drastic global and regional climate impacts, like droughts and colder winters, especially in Northwestern Europe.

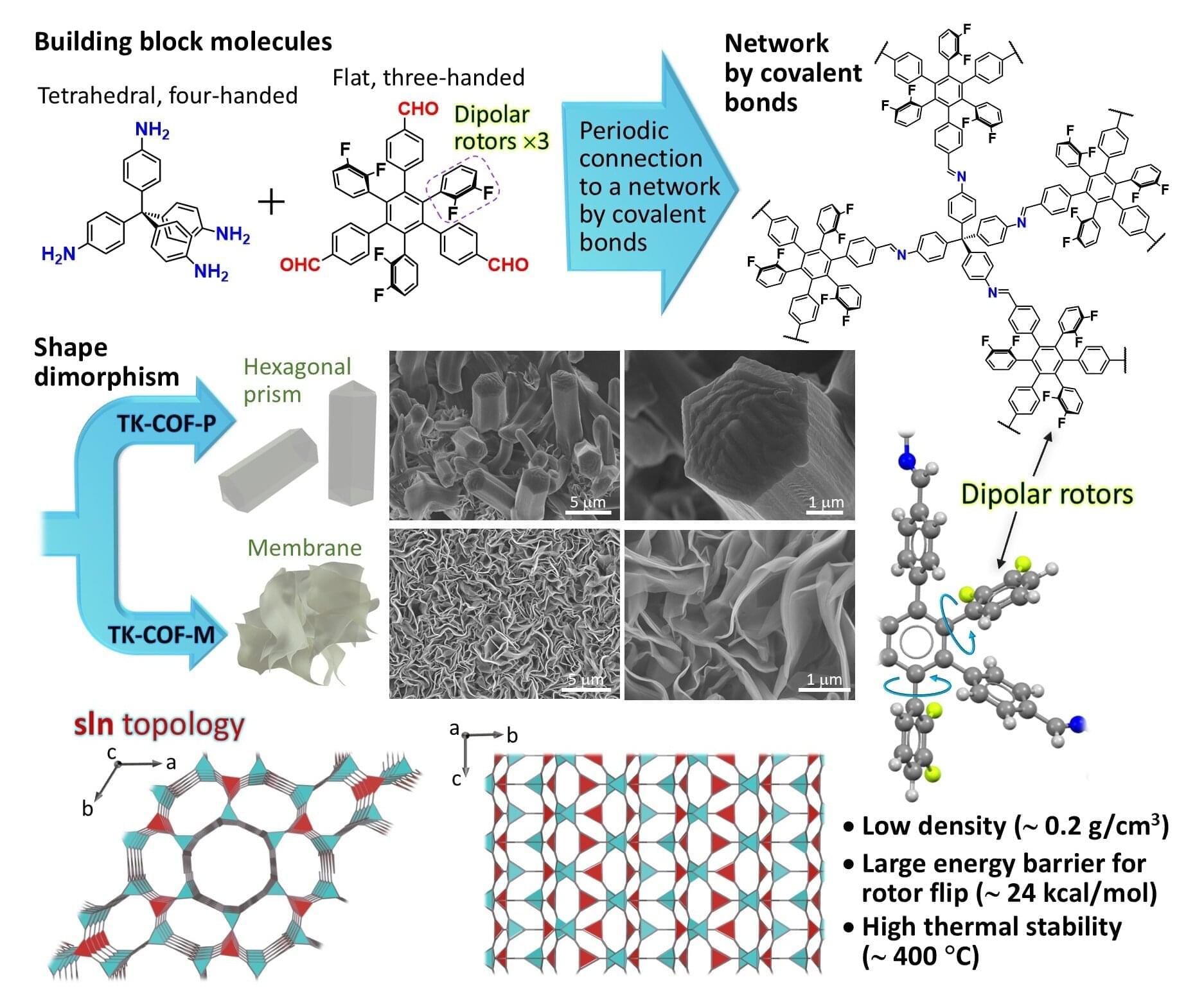

Researchers at Institute of Science Tokyo have created a new material platform for non-volatile memories using covalent organic frameworks (COFs), which are crystalline solids with high thermal stability. The researchers successfully installed electric-field-responsive dipolar rotors into COFs.

Due to the unique structure of the COFs, the dipolar rotors can flip in response to an electric field without being hampered by a steric hindrance from the surroundings, and their orientation can be held at ambient temperature for a long time, which are necessary conditions for non-volatile memories. The study is published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society.

Humans have made great efforts to record information by inventing recording media such as clay, paper, compact disks, and semiconductor memories. As the physical entity that holds information—such as indentations, characters, pits, or transistors—becomes smaller and its areal density becomes higher, the information is stored with higher density. In rewritable memories, the class called “non-volatile memories” are suitable for storing data for a long time, such as for days and years.

In 3D bioprinting, researchers use living cells to create functional tissues and organs. Instead of printing with plastic, they print with living cells. This comes with great challenges. Cells are fragile and wouldn’t survive a regular 3D printing process. That’s why Levato’s team developed a special bio-ink, a mix of living cells and nourishing gels that protect the cells during the printing process.

With the advancements in bio-inks, layer-by-layer 3D bioprinting became possible. But this method is still time-consuming and puts a lot of stress on the cells. Researchers from Utrecht came up with a solution: volumetric bioprinting.

Volumetric bioprinting is faster and gentler on cells. Using cell-friendly laser light, a 3D structure is created all at once. “To build a structure, we project a series of light patterns into a spinning tube filled with light-sensitive gel and cells,” Levato explains. “Where the light beams converge, the material solidifies. This creates a full 3D object in one go, without having to touch the cells.” To do this, it is crucial to know exactly where the cells are in the gel. GRACE now makes that possible.