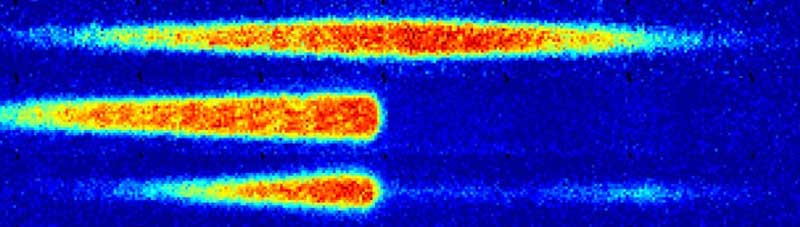

face_with_colon_three year 2017 This is essentially a light based battery 🔋 😳

Device running on atoms, not electrons, could power atom-based circuits.

Researchers from The University of Queensland have discovered the active compound from an edible mushroom that boosts nerve growth and enhances memory.

Professor Frederic Meunier from the Queensland Brain Institute said the team had identified new active compounds from the mushroom, Hericium erinaceus. This type of edible mushroom, commonly known as the Lion’s Mane Mushroom, is native to North America, Europe, and Asia. It is commonly sought after for its unique flavor and texture, and it is also used in traditional Chinese medicine to boost the immune system and improve digestive health.

Researchers have discovered lion’s mane mushrooms improve brain cell growth and memory in pre-clinical trials.

Science fiction films love to show off huge leaps in technology. The latest Avatar movie features autonomous, spider-like robots that can build a whole city within weeks. There are space ships that can carry frozen passengers lightyears away from Earth. In James Cameron’s imagination, we can download our memories and then upload them into newly baked bodies. All this wildly advanced tech is controlled through touch-activated, transparent, monochrome and often blue holograms. Just like a thousand other futuristic interfaces in Hollywood.

When we are shown a glimpse of the far future through science fiction films, there are omnipresent voice assistants, otherworldly wearables, and a whole lot of holograms. For whatever reason these holograms are almost always blue, floating above desks and visible to anyone who might stroll by. This formula for futuristic UI has always baffled me, because as cool as it looks, it doesn’t seem super practical. And yet, Hollywood seems to have an obsession with imagining future worlds washed in blue light.

Perhaps the Hollywood formula is inspired by one of the first holograms to grace the silver screen: Princess Leia telling Obi-Wan Kenobi that he is their only hope. Star Wars served as an inspiration for future sci-fi ventures, so it follows that other stories might emulate the original. The Avatar films have an obvious penchant for the color blue, and so the holograms that introduce us to the world of Pandora and the native Na’vi are, like Leia, made out of blue light.

An international team of scientists has found a way to regenerate kidneys damaged by disease, restoring function and preventing kidney failure. The discovery could drastically improve treatments for complications stemming from diabetes and other diseases.

Diabetes causes many problems in the body, but one of the most prevalent is kidney disease. Extended periods of elevated blood sugar can damage nephrons, the tiny filtering units in the kidneys, which can lead to kidney dysfunction and eventually failure.

For the new study, researchers in Singapore and Germany investigated a potential culprit – a protein known as interleukin-11 (IL-11), which has been implicated in causing scarring to other organs in response to damage.

Researchers have come up with a new way to use 3D printing to make a new superalloy.

A group of researchers has developed a new superalloy resistant to high temperatures. This could if ever brought into production, prove revolutionary for the future of turbines.

This would increase its efficiency and decrease waste heat.

Craig Fritz/Sandia Labs.

At present, steam turbine blades, bearings, and seals are made of metal that tends to soften and elongate well before its melting point, which is one issue restricting the output of today’s power plants. If these issues are resolved, it is possible to increase the temperature of anything that uses a steam turbine to convert heat into electricity.

FRIDA can create finger paintings based on human inputs, photographs, and music.

“AI is the future!” is a statement of the past now, as AI is no longer the future but our present. After ChatGPT shocked the whole world with its abilities, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University created an AI-powered robot that could create exceptional artwork on physical canvas with the help of simple text prompts, according to a press release.

The FRIDA robot (the Framework and Robotics Initiative for Developing Arts) can create unique paintings using photographs, human inputs, or even music. The final result is somewhat a resemblance to a basic finger painting.

Carnegie Mellon University.

After ChatGPT shocked the whole world with its abilities, researchers at Carnegie Mellon University created an AI-powered robot that could create exceptional artwork on physical canvas with the help of simple text prompts, according to a press release.

A new literature review of papers on “common mycorrhizal networks” seems to indicate the science behind them is not as strong as once thought.

Akin to the Ents from “The Lord of the Rings,” there is an idea in modern botany that trees can “talk” to one another through a delicate web of fungus filaments that grows underground. The idea is so alluring that it has gained traction in popular culture and has even been termed the “wood-wide network.”

However, according to Justine Karst, associate professor from the University of Alberta’s Faculty of Agricultural, Life, and Environmental Sciences, it could all be nonsense.

Jacquesvandinteren/iStock.

“It’s great that CMN research has sparked interest in forest fungi, but it’s important for the public to understand that many popular ideas are ahead of the science,” says Karst.

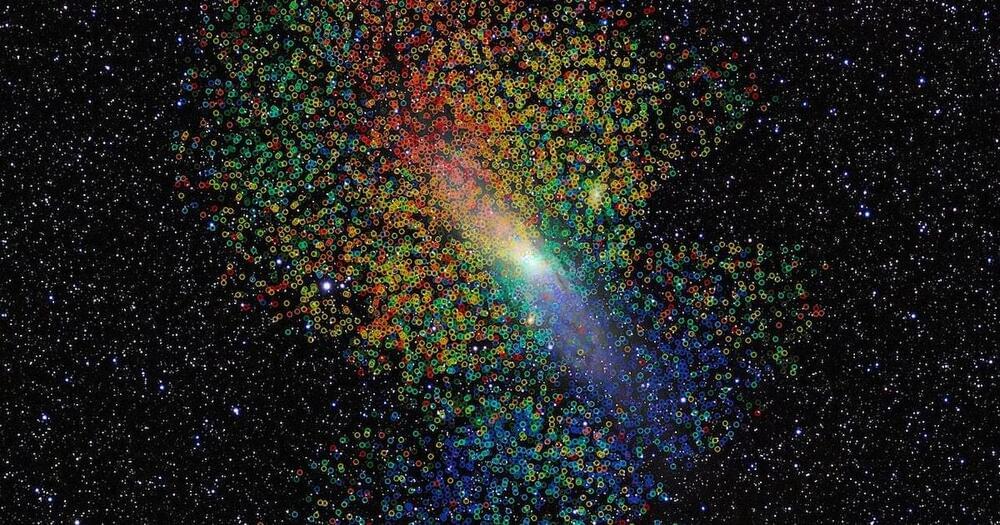

The powerful flare caused a radio blackout over South America.

The Sun sent out a very powerful solar flare in the morning hours of Saturday EST time. NASA’s Solar Dynamic Observatory captured a video of the same.

Sunspots and solar flares.

Thomas Faull/iStock.

Solar flares are powerful eruptions of electromagnetic radiation from a region of the Sun with an intense magnetic field. This high-intensity magnetic field temporarily stops the convection process on the solar surface, which cools down the region. When observed from a distance, it appears darker than the solar disc and is known as a sunspot.

Meta is preparing a fresh round of job cuts, according to a report from the Financial Times. Two people familiar with the matter told the Financial Times that there has been a lack of clarity around budgets and the future headcount at the company. The job cuts are expected to take place around March, but it’s unknown how people could be affected.

The lack of clarity has resulted in staff noting that not much work is getting done, as managers have been unable to plan ahead, the report says. Certain budgets that would normally be finalized by the end of the year still haven’t been finalized, and decisions that would usually take days to be signed off on are now taking a month in some cases.

Meta did not immediately respond to TechCrunch’s request for comment.