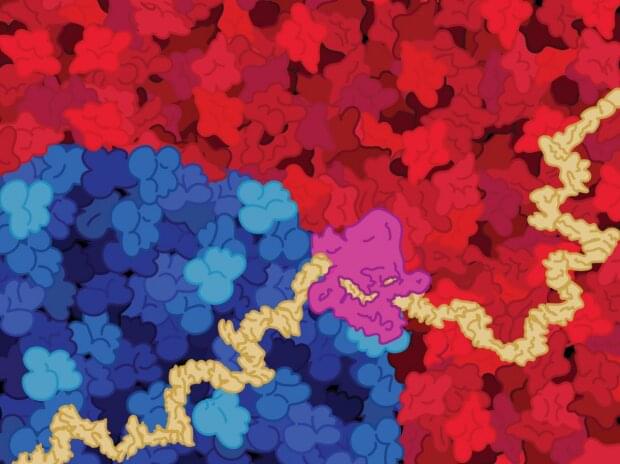

A study from Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago demonstrated that Botulinum toxin (Botox) injected in the pylorus during endoscopy improves chronic nausea and vomiting in children who have a disorder of gut-brain interaction (DGBI). These debilitating symptoms not attributed to a defined illness have previously been called functional gastrointestinal disorders before the newer DGBI classification. The study’s findings point to a novel understanding of the condition’s pathology – pylorus that is failing to relax and allow food to effectively pass into the small intestine resulting in symptoms of nausea, vomiting, early satiety and bloating.

Results were published in the Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition.

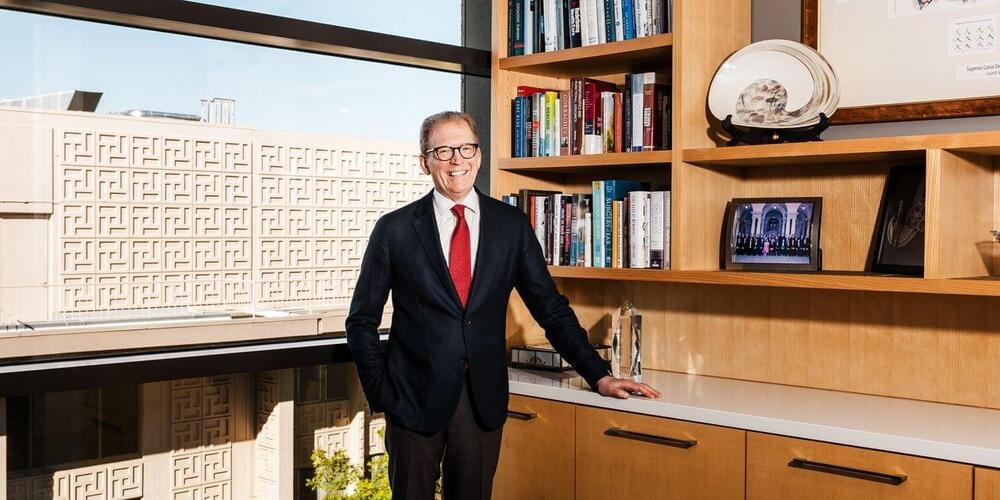

“Our results suggest that chronic nausea and vomiting might be caused by pyloric dysfunction, rather than abnormal peristalsis, which is the rhythmic contraction and relaxation of digestive tract muscles needed to move foods and liquids through the gastrointestinal system,” said lead author Peter Osgood, MD, gastroenterologist at Lurie Children’s and Assistant Professor of Pediatrics at Northwestern University Feinberg School of Medicine. “This is a paradigm shift in our understanding of mechanistic pathology. Importantly, it opens the door to a more targeted use of Botox specifically in children who are found to have pyloric dysfunction during endoscopy, and for whom the current medications are not effective.”