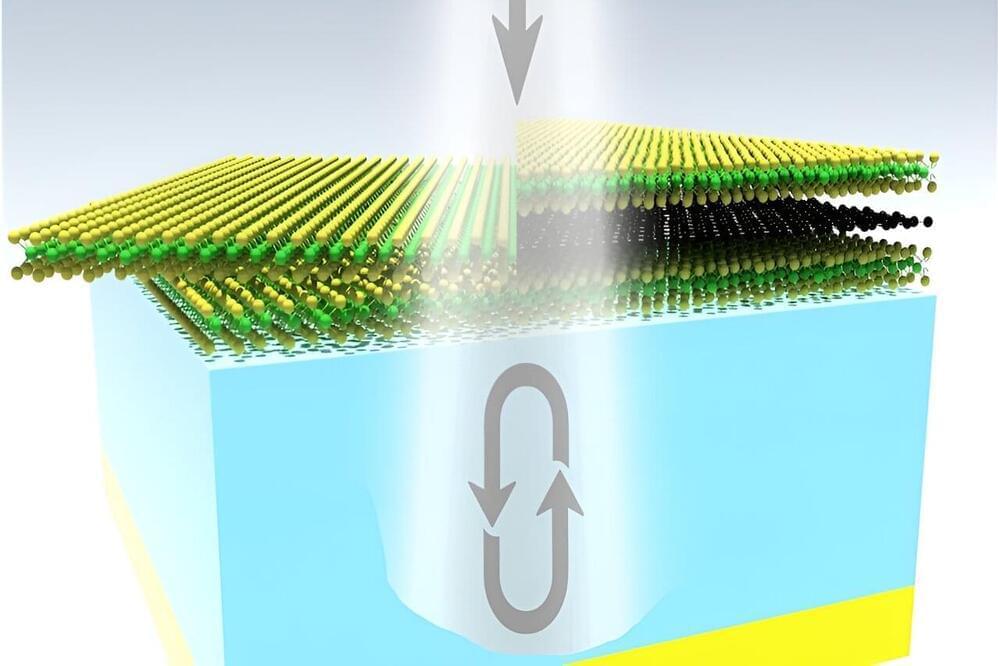

A University of Minnesota-led team has, for the first time, engineered an atomically thin material that can absorb nearly 100% of light at room temperature, a discovery that could improve a wide range of applications from optical communications to stealth technology. Their paper has been published in Nature Communications.

Materials that absorb nearly all of the incident light —meaning not a lot of light passes through or reflects off of them—are valuable for applications that involve detecting or controlling light.

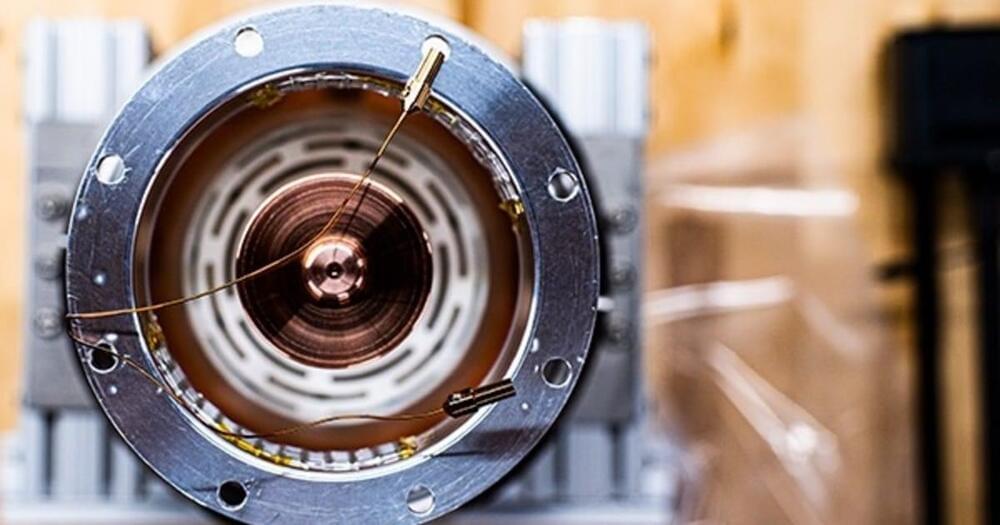

“Optical communications are used in basically everything we do,” said Steven Koester, a professor in the College of Science and Engineering and a senior author of the paper. “The internet, for example, has optical detectors connecting fiber optic links. This research has the potential to allow these optical communications to be done at higher speeds and with greater efficiency.”