Airbnb investors are flocking to South Texas, where they see a chance to capitalize on relatively cheap homes and proximity to Musk’s SpaceX.

Paul McCartney says he has used artificial intelligence to create “the last Beatles record,” featuring vocals from the late John Lennon.

Come together right now, with AI.

More than 50 years after the group’s final studio album, Paul McCartney says he has used artificial intelligence to create what he called “the last Beatles record.”

Now I know why Tim Cook isn’t wearing Goggles. I live Pi, but this is a bit weird when cellphones do the same thing.

Diyode has created a pair of night vision goggles using a Raspberry Pi with a cool HUD interface.

Highlights from the latest #nvidia keynote at Computex in Taiwan, home of TSMC and is the world’s capital of semiconductor manufacturing and chip fabrication. Topics include @NVIDIA’s insane H100 datacenter GPUs, Grace Hopper superchips, GH200 AI supercomputer, and how these chips will power generative AI technologies like #chatgpt by #openai and reshape computing as we know it.

💰 Want my AI research and stock picks? Let me know: https://tickersymbolyou.com/survey/

⚠️ Get up to 17 FREE stocks with Moomoo: https://tickersymbolyou.com/moomoo.

Simply Wall Street’s Nvidia (NVDA Stock) Valuation: https://simplywall.st/stocks/us/semiconductors/nasdaq-nvda/nvidia?via=tsyou.

Taiwan Semiconductor (TSM Stock) Valuation: https://simplywall.st/stocks/us/semiconductors/nyse-tsm/taiw…?via=tsyou.

Timestamps for this Nvidia Keynote Supercut:

Editor’s note: For a more mainstream assessment of this idea, see this article by Dr. Ethan Siegel.

Sir Roger Penrose, a mathematician and physicist from the University of Oxford who shared the Nobel Prize in physics in 2020, claims our universe has gone through multiple Big Bangs, with another one coming in our future.

Penrose received the Nobel for his working out mathematical methods that proved and expanded Albert Einstein’s general theory of relativity, and for his discoveries on black holes, which showed how objects that become too dense undergo gravitational collapse into singularities – points of infinite mass.

Artificial intelligence-based video generation platform Synthesia has raised $90 million from investors including Nvidia, the company told CNBC exclusively.

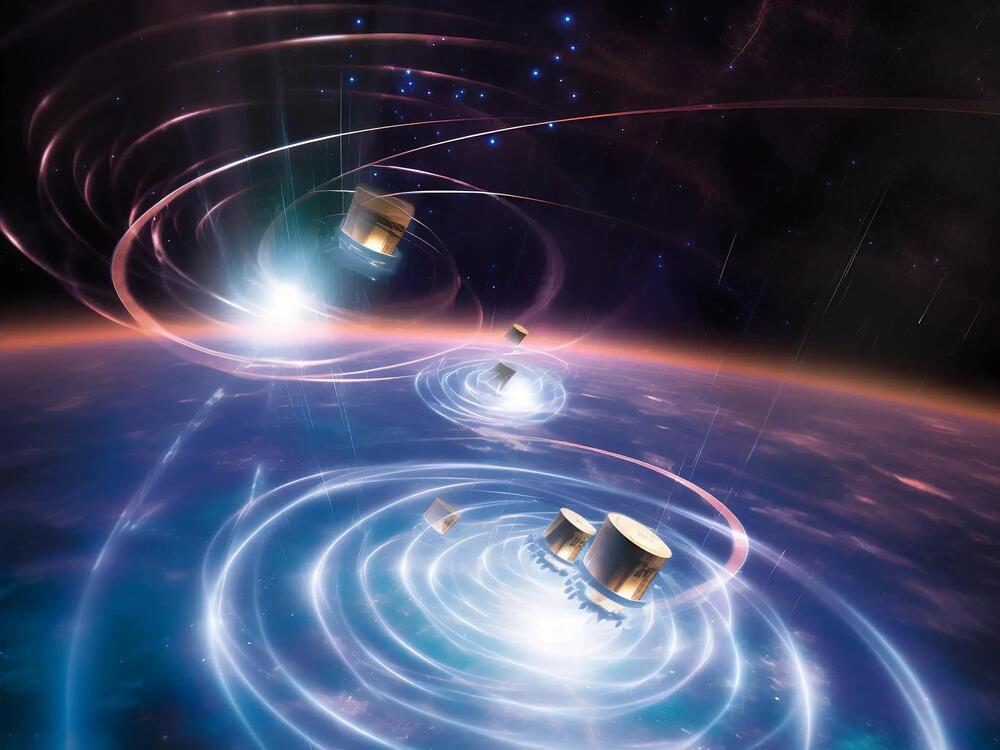

Researchers have reached a significant milestone in the field of quantum gravity research, finding preliminary statistical support for quantum gravity.

In a study published in Nature Astronomy on June 12, a team of researchers from the University of Naples “Federico II,” the University of Wroclaw, and the University of Bergen examined a quantum-gravity model of particle propagation in which the speed of ultrarelativistic particles decreases with rising energy. This effect is expected to be extremely small, proportional to the ratio between particle energy and the Planck scale, but when observing very distant astrophysical sources, it can accumulate to observable levels. The investigation used gamma-ray bursts observed by the Fermi telescope and ultra-high-energy neutrinos detected by the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, testing the hypothesis that some neutrinos and some gamma-ray bursts might have a common origin but are observed at different times as a result of the energy-dependent reduction in speed.

In the digital age, SaaS businesses have started embracing transformative technologies, such as Artificial intelligence (AI) and cloud computing. According to a research firm, the market for artificial intelligence (AI) is nearly 100 billion USD, which is expected to grow twentyfold by 2030, up to almost 2 trillion USD.

Although AI promises revolutionary advancements and cloud computing enables efficient storage and processing of massive amounts of data, their rapid adoption also raises concerns about cybersecurity. In 2021, the global cost of cybercrime was estimated to be $6 trillion.

Local language data helps automated systems understand and respond to users in their own language and can help businesses reach their target audiences more effectively, said Ganesh Gopalan, founder and CEO of AI startup Gnani.ai, during a panel discussion at the Mint Digital Innovation Summit & Awards on Friday.

“If we don’t have, firstly, content in the local language, if we can’t talk to machines in the local language, then it is not possible for no system to work and, you know, reach the right audience,” said Gopalan.

The panel discussion also included Vivekanand Pani, Co-founder, Reverie Language Technologies, who agrees that to develop an AI tool for any language, the availability of data is crucial.