OpenAI this week signaled it’ll soon begin charging for ChatGPT, its viral AI-powered chatbot that can write essays, emails, poems and even computer code. In an announcement on the company’s official Discord server, OpenAI said that it’s “starting to think about how to monetize ChatGPT” as one of the ways to “ensure [the tool’s] long-term viability.”

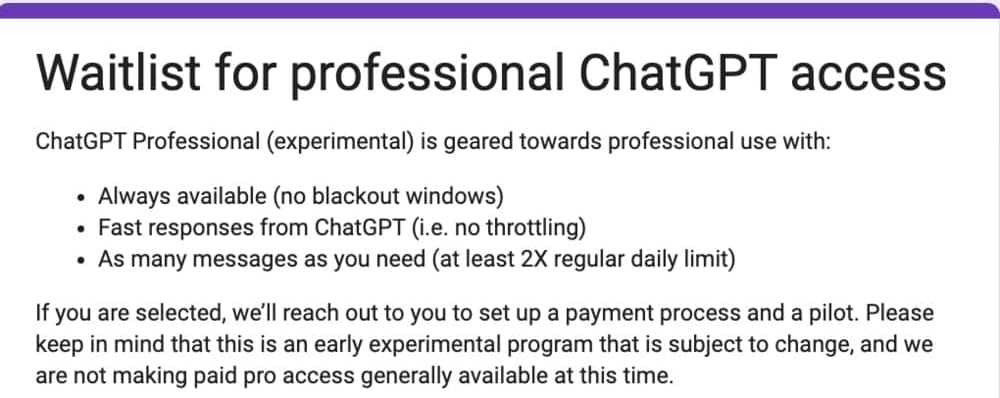

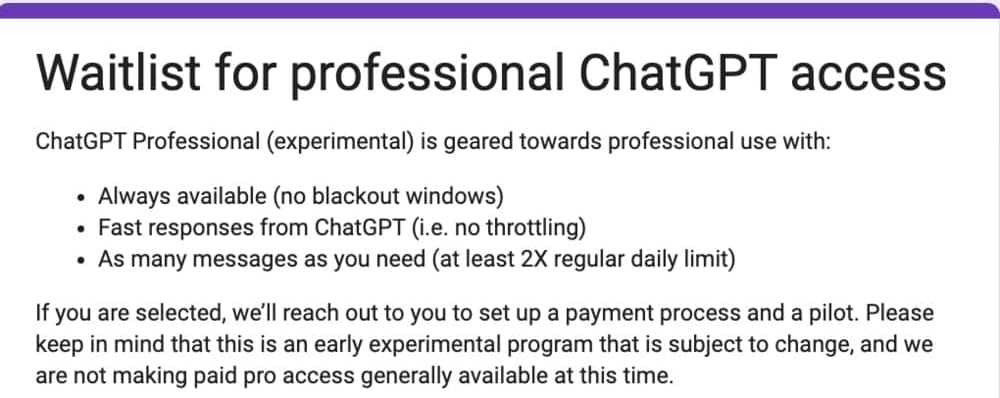

The monetized version of ChatGPT will be called ChatGPT Professional, apparently. That’s according to a waitlist link OpenAI posted in the Discord server, which asks a range of questions about payment preferences including “At what price (per month) would you consider ChatGPT to be so expensive that you would not consider buying it?”

The waitlist also outlines ChatGPT Professional’s benefits, which include no “blackout” (i.e. unavailability) windows, no throttling and an unlimited number of message with ChatGPT — “at least 2x the regular daily limit.” OpenAI says that those who fill out the waitlist form may be selected to pilot ChatGPT Professional, but that the program is in the experimental stages and won’t be made widely available “at this time.”