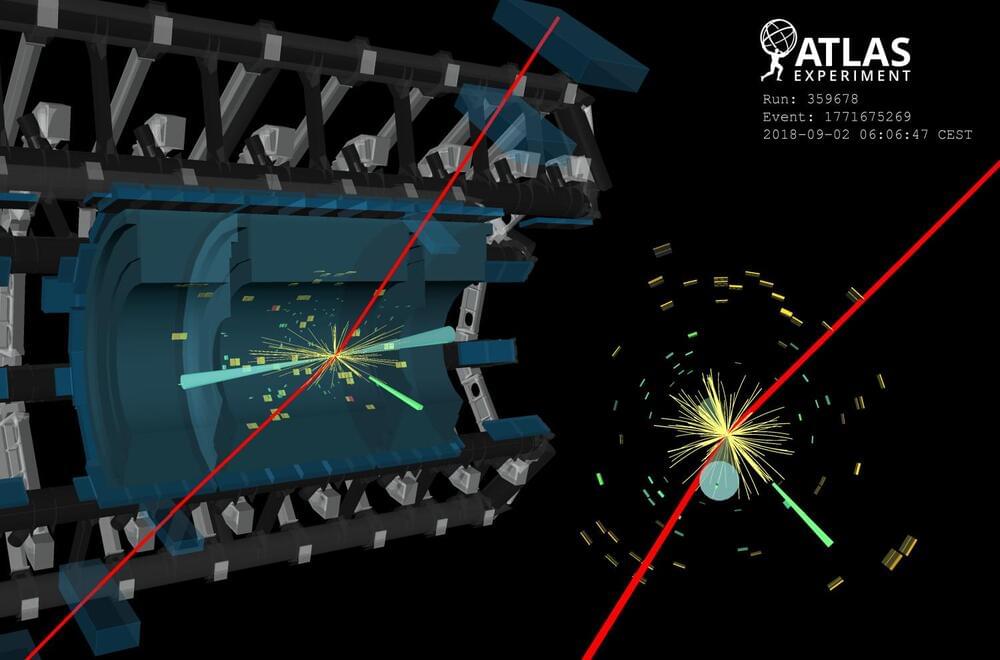

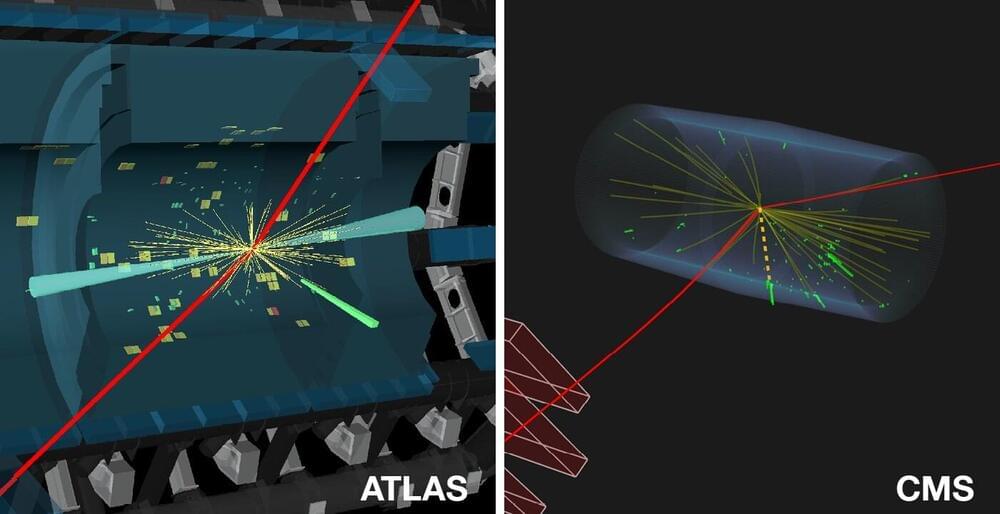

The discovery of the Higgs boson in 2012 marked a significant milestone in particle physics. Since then, researchers at the ATLAS and CMS Collaborations have been diligently investigating its properties and probing for rare production and decay channels. Among the rare decays, the process where the Higgs boson decays into a Z boson and a photon (H → Zγ) has raised considerable attention, especially given the significant dataset collected during Run 2 of the Large Hadron Collider. Figure 1: The Zγ invariant mass distribution of events from all ATLAS and CMS analysis categories. The data (circles with error bars) in each category are weighted by ln(1 + S/B) and summed, where S and B are the observed signal and background yields in that category and in the 120–130 GeV interval, derived from the fit to data. The fitted signal-plus-background (background) terms are represented by a red solid (blue dashed) line. In the lower panel, the data and the two models are compared after subtraction of the estimated background. (Image: CERN) This is a special kind of decay – the Higgs boson does not couple directly to the Zγ pair; instead, the decay proceeds via an intermediate ‘loop’ of virtual particles. Thus, in the Standard Model, the decay probability (or branching fraction) for H → Zγ is predicted to be small – around 1.5 ×10–3, for a Higgs boson mass near 125 GeV. Theories that go beyond the Standard Model predict this branching fraction to deviate, as new particles interacting with the Higgs boson may also contribute to this loop. Exploring these variations provides valuable insights into both physics beyond the Standard Model and the nature of the Higgs boson. The ATLAS and CMS Collaborations have independently conducted extensive searches for the H → Zγ process. Both searches employ similar strategies, reconstructing the Z boson through its decays into pairs of electrons or muons. Signal events are identified as a narrow peak in the Zγ invariant mass distribution. To enhance the sensitivity, researchers exploited the most frequent Higgs-boson production modes and categorised events based on the characteristics of these production processes. They also used advanced machine-learning techniques, such as boosted decision trees, to distinguish between signal and background events. The ATLAS and CMS Collaborations have joined forces to report first evidence of the H → Zγ decay, with a significance of 3.4 standard deviations. Figure 2: Negative log-likelihood scan of the signal strength μ from the analysis of ATLAS data (blue line), CMS data (red line), and the combined result (black line). (Image: CERN) Recognising the importance of this decay channel, the ATLAS and CMS Collaborations joined forces to maximise the statistical power and sensitivity of their analyses. By combining the data sets collected by both experiments during Run 2 of the LHC (2015−2018), researchers have significantly increased the statistical precision and expanded the reach of their search. This collaborative effort allowed for a more precise and robust measurement. Figure 1 displays the observed distribution of the mass of the Zγ system in the combined data sample. Figure 2 presents the negative log-likelihood scan to identify the most likely signal strength that best describes the observed data. The signal strength (μ) is defined as the ratio of the Higgs-boson production cross-section times the H → Zγ decay branching fraction to its Standard-Model prediction. This analysis reveals evidence for the H → Zγ decay, with a significance of 3.4 standard deviations. This means that the probability that this signal is actually caused by a statistical fluctuation is smaller than 0.04%. The measured branching fraction for H → Zγ is 3.4 ± 1.1 ×10–3 and the observed signal yield is measured to be 2.2 ± 0.7 times the Standard-Model prediction. This means that the decay is seen a little more than twice as often as would be expected by the Standard Model. Although the uncertainty on the present measurement is still quite large, these findings open the door to valuable insights into the behaviour and properties of the Higgs boson. Looking ahead, by the end of LHC Run 3 the collected data is expected to triple the size of the dataset analysed here. This will allow ATLAS and CMS researchers to study this rare decay channel in even more detail, and to use this channel to probe for new physics beyond the Standard Model. About the event display: Event display of a candidate H→ Zγ event with the Z boson decaying μ+μ-. The transverse momenta of the two muon candidates, shown in red. The photon candidate is reconstructed as an unconverted photon with a transverse momentum of 32.5 GeV. Two jets are represented by light blue cones. The green boxes correspond to energy deposits in cells of the electromagnetic calorimeter, while yellow boxes correspond to energy deposits in cells of the hadronic calorimeter. Learn more Evidence for the Higgs boson decay to a Z boson and a photon at the LHC (ATLAS-CONF-2023–025) LHCP 2023 presentation by Toyoko Orimoto: Higgs boson rare production and decay at ATLAS and CMS LHCP 2023 presentation by Chiara Arcangeletti: Measurement of Higgs boson production and properties LHC experiments see first evidence for rare Higgs boson decay into two different bosons, CMS briefing, May 2023 ATLAS Collaboration: A search for the Zγ decay mode of the Higgs boson in pp collisions at 13 TeV with the ATLAS detector (Phys. Lett. B 809 (2020) 135,754, arXiv: 2005.05382, see figures) CMS Collaboration: Search for Higgs boson decays to a Z boson and a photon in proton–proton collisions at 13 TeV (Accepted for publication in J. High Energy Phys, arXiv: 2204.12945, see figures) ATLAS searches for rare Higgs boson decays into a photon and a Z boson, ATLAS Physics Briefing, April 2020 A possible new decay mode of the Higgs boson, CMS briefing, April 2022 Summary of new ATLAS results from LHCP 2023, ATLAS News, May 2023.