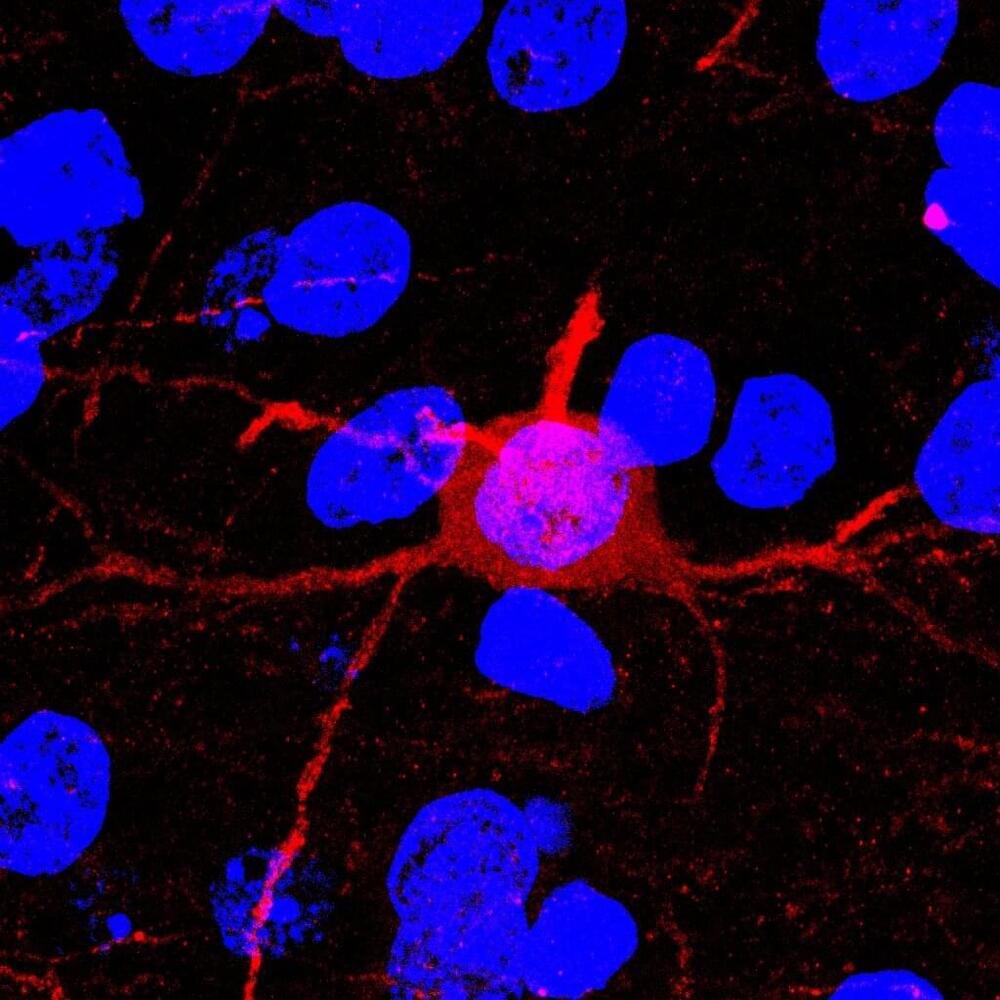

The human fingertip is an exquisitely sensitive instrument for perceiving objects in our environment via the sense of touch. A team of Chinese scientists has mimicked the underlying perceptual mechanism to create a bionic finger with an integrated tactile feedback system capable of poking at complex objects to map out details below the surface layer, according to a recent paper published in the journal Cell Reports Physical Science.

“We were inspired by human fingers, which have the most sensitive tactile perception that we know of,” said co-author Jianyi Luo of Wuyi University. “For example, when we touch our own bodies with our fingers, we can sense not only the texture of our skin, but also the outline of the bone beneath it. This tactile technology opens up a non-optical way for the nondestructive testing of the human body and flexible electronics.”

According to the authors, previously developed artificial tactile sensors could only recognize and discriminate between external shapes, surface textures, and hardness. But they aren’t capable of sensing subsurface information about those materials. This usually requires optical technologies, such as CT scanning, PET scans, ultrasonic tomography (which scans the exterior of a material to reconstruct an image of its internal structure), or MRIs, for example. But all of these methods also have drawbacks. Similarly, optical profilometry is often used to measure the surface’s profile and finish, but it only works on transparent materials.