The radio astronomy experiment LuSEE-Night will test technologies for radio telescopes on the far side of the moon.

Abstract: Full Publication #OpenAccess.

Scalable fabrication of two-dimensional (2D) arrays of quantum dots (QDs) and quantum rods (QRs) with nanoscale precision is required for numerous device applications. However, self-assembly–based fabrication of such arrays using DNA origami typically suffers from low yield due to inefficient QD and QR DNA functionalization. In addition, it is challenging to organize solution-assembled DNA origami arrays on 2D device substrates while maintaining their structural fidelity. Here, we reduced manufacturing time from a few days to a few minutes by preparing high-density and rehydration process. We used a surface-assisted large-scale assembly (SALSA) method to construct 2D origami lattices directly on solid substrates to template QD and QR 2D arrays with orientational control, with overall loading yields exceeding 90%. Our fabrication approach enables the scalable, high fidelity manufacturing of 2D addressable QDs and QRs with nanoscale orientational and spacing control for functional 2D photonic devices.

Dehydration and surface-assisted assembly enable rapid, scalable quantum dot and quantum rod 2D arrays with nanoscale precision.

ChatGPT isn’t just a chatbot anymore.

OpenAI’s latest upgrade grants ChatGPT powerful new abilities that go beyond text. It can tell bedtime stories in its own AI voice, identify objects in photos, and respond to audio recordings. These capabilities represent the next big thing in AI: multimodal models.

“Multimodal is the next generation of these large models, where it can process not just text, but also images, audio, video, and even other modalities,” says Dr. Linxi “Jim” Fan, Senior AI Research Scientist at Nvidia.

OpenAI’s chatbot learns to carry a conversation—and expect competition.

The Transportation Authority of Marin board has voted to accept a framework to accelerate the transition to electric vehicles, in some cases faster than required under state law.

The “Marin Countywide Electric Vehicle Acceleration Strategy,” developed by the interagency Marin County Climate and Energy Partnership, is meant to provide a playbook of policies and actions for jurisdictions to employ to ready their communities for a growing number of electric vehicles.

Several Marin communities have already accepted the strategy, and the Transportation Authority of Marin board did so on Thursday. The authority is a state-managed congestion management agency that also provides rebates to public agencies for installing charging stations and electrifying their vehicle fleets.

Researchers used laser pulses to enhance MXene’s electrode properties, leading to a potential breakthrough in rechargeable battery technology that could surpass traditional lithium-ion batteries.

As the global community shifts towards renewable energy sources like solar and wind, the demand for high-performance rechargeable batteries is intensifying. These batteries are essential for storing energy from intermittent renewable sources. While today’s lithium-ion batteries are effective, there’s room for improvement. Developing new electrode materials is one way to improve their performance.

Gene therapy company Genflow Biosciences has received positive feedback from Belgium’s Federal Agency for Medicines and Health Products as it seeks to move into human clinical trials. Genflow is developing gene therapies that target the aging process, with a focus on reducing and delaying age-related diseases.

Genflow’s approach involves the use of adeno-associated virus (AAV) vectors to deliver copies of the Sirtuin-6 (SIRT6) gene variant found in centenarians into cells. Sirtuins are a group of proteins that play a vital role in regulating various cellular processes. In recent years, SIRT6 has gained attention for its potential role in promoting healthy aging.

Genflow says it has received written advice from the FAHMP to commence clinical trials of its lead compound (GF-1002) in patients suffering from NASH, an aggressive form of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, rather than in healthy volunteers. While further discussions and agreement with the European Medicine Agency (EMA) are still required, Genflow says that it expects a NASH clinical trial to commence in approximately 18 months.

For nearly five years, Austin Energy’s EVs for Schools program has provided access to electric vehicle charging infrastructure and related technology curriculum to more than 150 schools across Central Texas. Now, AE is gearing up for the rollout of its upgraded program, adapted to meet the changing landscape of EV technology.

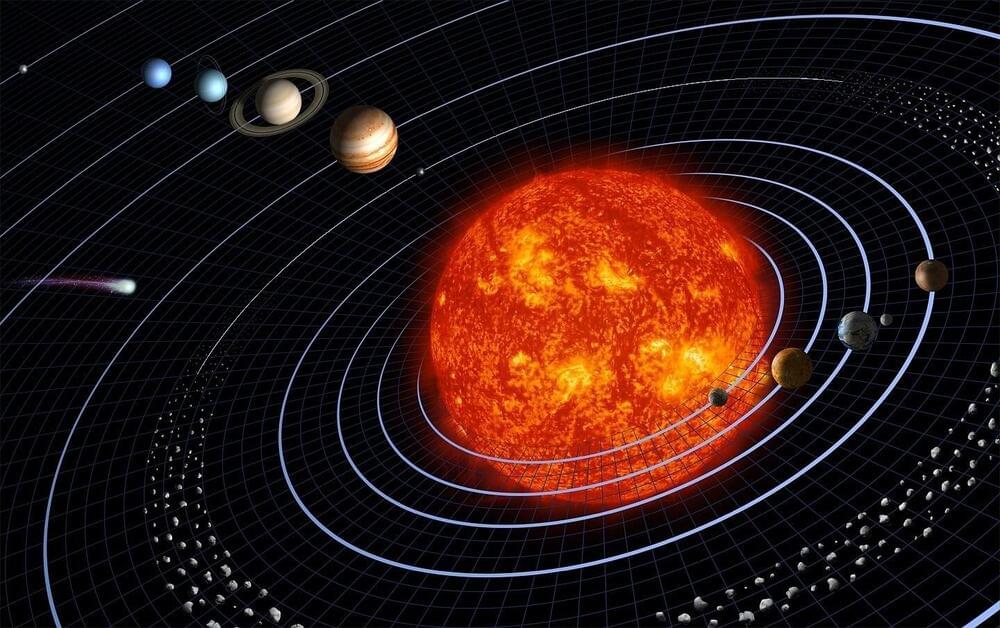

India’s sun-monitoring spacecraft has crossed a landmark point on its journey to escape “the sphere of Earth’s influence”, its space agency said, days after the disappointment of its moon rover failing to awaken.

The Aditya-L1 mission, which started its four-month journey towards the center of the solar system on September 2, carries instruments to observe the sun’s outermost layers.

“The spacecraft has escaped the sphere of Earth’s influence,” the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) said in a statement late Saturday.