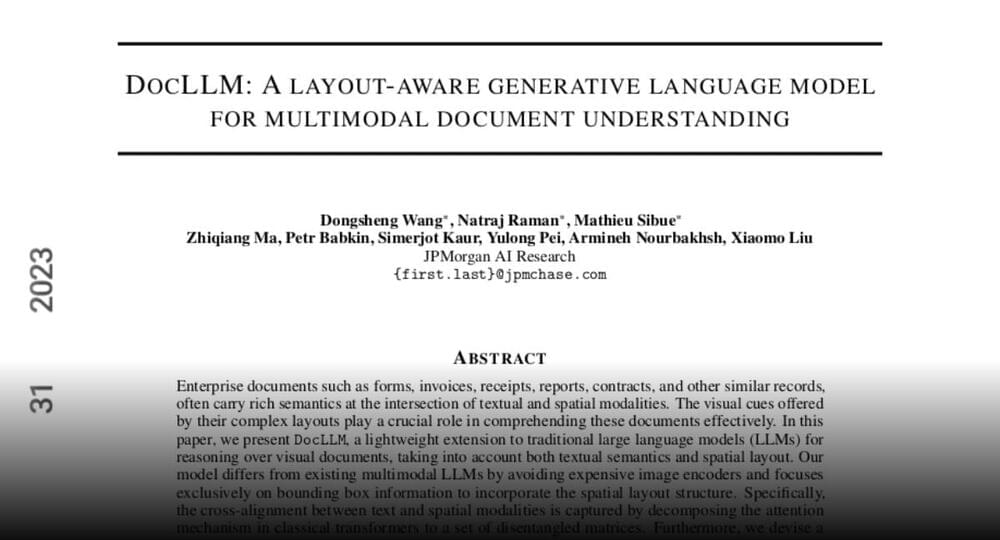

Join the discussion on this paper page.

Machine learning could also help us create more data to study. By identifying perhaps as many as 10 times more earthquakes in seismic data than we are aware of, Beroza, Mousavi, and Margarita Segou, a researcher at the British Geological Survey, determined that machine learning is useful for creating more robust databases of earthquakes that have occurred; they published their findings in a 2021 paper for Nature Communications. These improved data sets can help us—and machines—understand earthquakes better.

“You know, there’s tremendous skepticism in our community, with good reason,” Johnson says. “But I think this is allowing us to see and analyze data and realize what those data contain in ways we never could have imagined.”

While some researchers are relying on the most current technology, others are looking back at history to formulate some pretty radical studies based on animals. One of the shirts I collected over 10 years of attending geophysics conferences features the namazu, a giant mythical catfish that in Japan was believed to generate earthquakes by swimming beneath Earth’s crust.

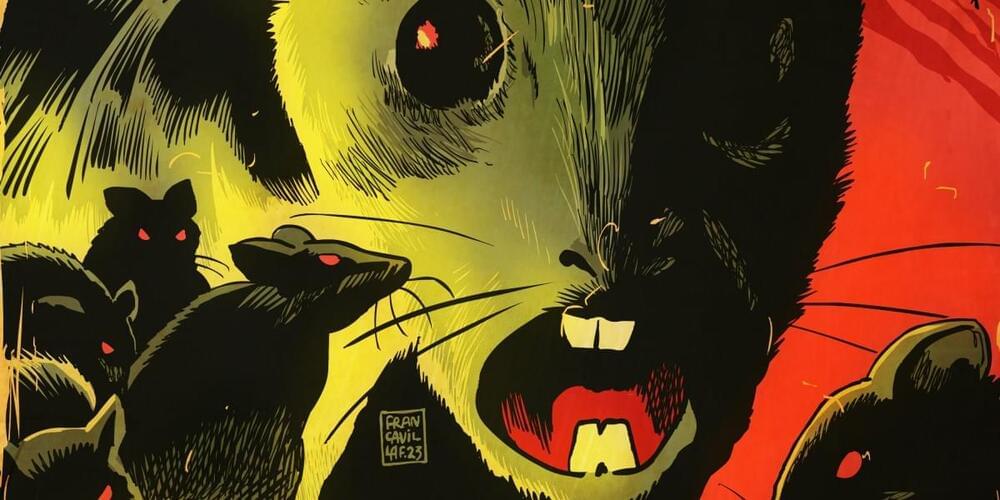

The US is trying its best to slow China down.

However, an equally serious challenger has now emerged in the form of SEIDA, a Chinese startup founded by a veteran Silicon Valley software executive.

Liguo “Recoo” Zhang, the CEO of SEIDA, and three other Chinese-born colleagues left Siemens EDA, a U.S. unit of Siemens AG, aiming to break the foreign monopoly on Optical Proximity Correction (OPC) technology, reported Reuters.

The OPC tool is indispensable for designing advanced chips crucial for emerging technologies like artificial intelligence and quantum computing. SEIDA’s bold pitch attracted powerful Chinese investors, including Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp (SMIC), a leading Chinese microchip maker with alleged ties to China’s military.

In the modern digital age, where data flows freely and sensitive information is constantly in transit, secure communication has become essential. Traditional encryption methods, while effective, are not immune to the evolving threat landscape. This is where quantum key distribution (QKD) emerges as a revolutionary solution, offering unmatched security for transmitting sensitive data.

Image Credit: asharkyu/Shutterstock.com

The idea of quantum key distribution (QKD) dates back to Stephen Wiesner’s concept of quantum conjugate coding at Columbia University in the 1970s. Charles H. Bennett later built on this idea, introducing the first QKD protocol, BB84, in the 1980s, using nonorthogonal states. Since then, it has matured into one of the most established quantum technologies, commercially available for over 15 years.

As the cofounder of Google DeepMind, Shane Legg is driving one of the greatest transformations in history: the development of artificial general intelligence (AGI). He envisions a system with human-like intelligence that would be exponentially smarter than today’s AI, with limitless possibilities and applications. In conversation with head of TED Chris Anderson, Legg explores the evolution of AGI, what the world might look like when it arrives — and how to ensure it’s built safely and ethically.

If you love watching TED Talks like this one, become a TED Member to support our mission of spreading ideas: https://ted.com/membership.

Follow TED!

Twitter: / tedtalks.

Instagram: / ted.

Facebook: / ted.

LinkedIn: / ted-conferences.

TikTok: / tedtoks.

The TED Talks channel features talks, performances and original series from the world’s leading thinkers and doers. Subscribe to our channel for videos on Technology, Entertainment and Design — plus science, business, global issues, the arts and more. Visit https://TED.com to get our entire library of TED Talks, transcripts, translations, personalized talk recommendations and more.

Watch more: https://go.ted.com/shanelegg.

It’s no surprise that educators have an uneasy relationship with generative AI.

Education has always been centered around the human element, and it’s hard to imagine a world where machines can replace that.

Generative AI has sparked a tremendous backlash across the internet, as the early promise of the technology has been overshadowed by the wide range of problems it has introduced.

It’s true that no artist was asked if their work could be used to train these models. But even if the courts rule in favor of the machines, the practical application of the technology doesn’t seem worth the cost.

Generative AI is incredibly energy-intensive, surprisingly labor-intensive, and requires constant input — annotation — from human workers to keep it functional, lest it spiral into hallucinogenic nonsense.

Using ChatGPT for a playful Q&A session consumes an absurd amount of water; exchanging a mere 20 questions with the text generator is akin to pouring a 500ml bottle of clean freshwater down the drain.

The Chinese automaker sold over 3 million clean energy vehicles, with Tesla reporting just 1.35 million in the first three quarters of the year.

Chinese electric vehicle company Build Your Dreams (BYD) is set to become the largest EV maker in 2023, overtaking Tesla for the second year in a row.

BYD’s strategy of manufacturing budget-friendly vehicles has facilitated its expansion not only within China but also in international markets.