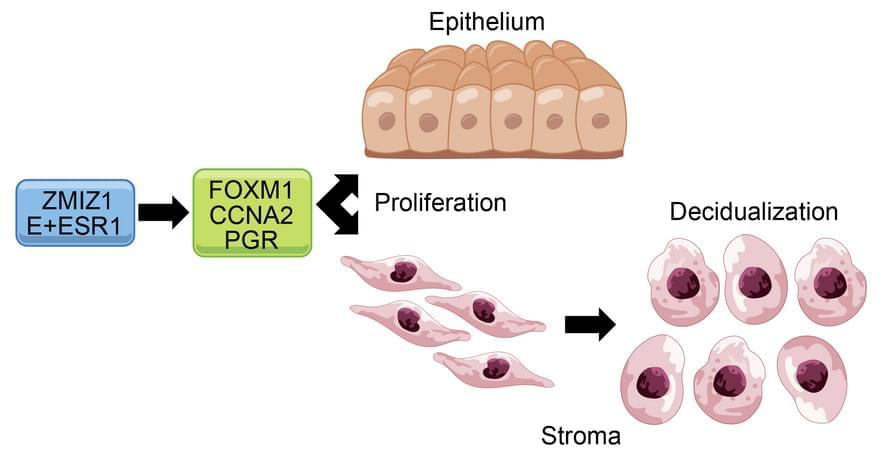

Francesco J. DeMayo & team discover uterine ZMIZ1 co-regulates estrogen receptor to establish and maintain pregnancy and general uterine health via cell growth responses and preventing uterine fibrosis:

The figure shows epithelial cell DNA synthesis (reflected by EdU incorporation) was inhibited by Zmiz1 deletion.

1Pregnancy & Female Reproduction Group, Reproductive and Development al Biology Lab, NIEHS, Research Triangle Park, North Carolina, USA.

2Inotiv-RTP, Durham, North Carolina, USA.

3Division of Hematology-Oncology, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Michigan School of Medicine, Ann Arbor, Michigan, USA.