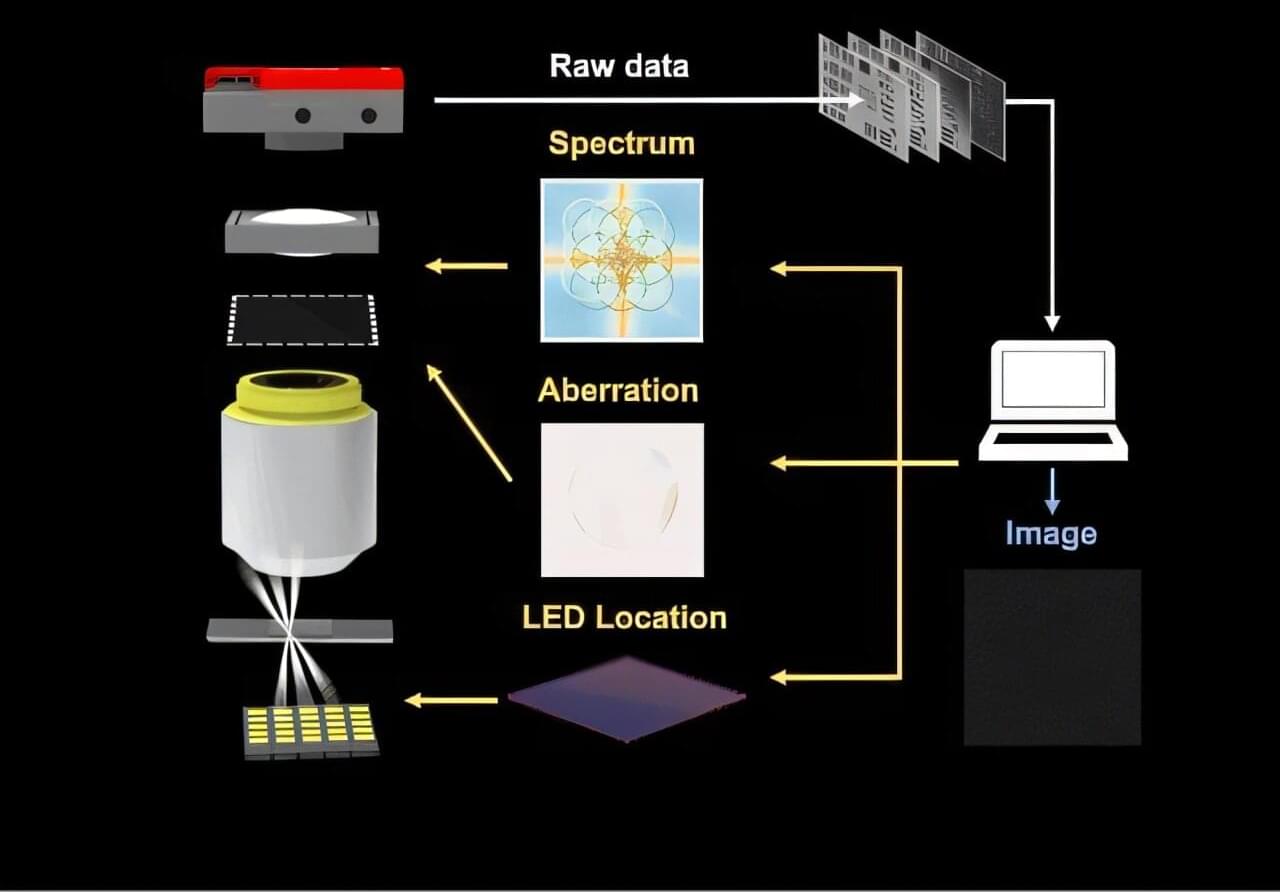

Professor Edmund Lam, Dr. Ni Chen and their research team from the Department of Electrical and Electronic Engineering under the Faculty of Engineering at the University of Hong Kong (HKU) have developed a novel uncertainty-aware Fourier ptychography (UA-FP) technology that significantly enhances imaging system stability in complex real-world environments. The research has been published in Light: Science & Applications.

Fourier ptychography, widely regarded as a cornerstone of computational imaging, enables wide field-of-view and high-resolution imaging with broad applications ranging from microscopy to X-ray and remote sensing. However, its practical implementation has long been hindered by misalignments, optical aberrations, and poor data quality—challenges common across computational imaging fields.

The team’s UA-FP framework innovatively incorporates uncertainty parameters into a fully differentiable computational model, enabling simultaneous system uncertainty quantification and correction and significant enhancement of imaging performance—even under suboptimal or interference-prone conditions. This advancement represents not only an advance in ptychography but also a transformative development for computational imaging as a whole.