For example, to compute the magnetic susceptibility, we simply select the operator \(A=\beta {({S}^{z})}^{2}\), where β = 1/T is the inverse temperature. Interestingly, this method of estimating thermal expectation values is insensitive to uniform spectral broadening of each peak, due to a cancellation between the numerator and denominator (see discussion resulting in equation (S69) in Supplementary Information). However, it is highly sensitive to noise at low ω, which is exponentially amplified by e−βω. To address this, we estimate the SNR for each DA(ω) independently and zero-out all points with SNR below three times the average SNR. This potentially introduces some bias by eliminating peaks with low signal but ensures that the effects of shot noise are well controlled.

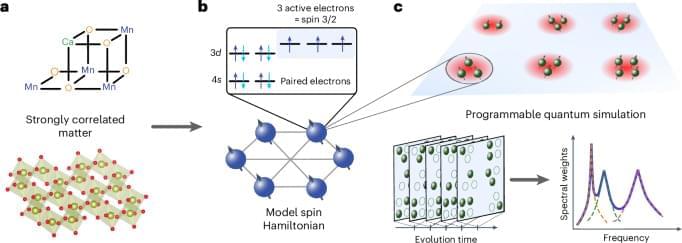

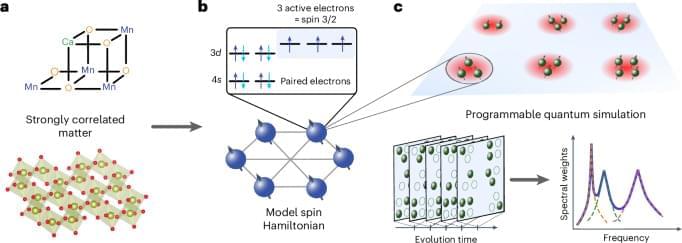

To quantify the effect of noise on the engineered time dynamics, we simulate a microscopic error model by applying a local depolarizing channel with an error probability p at each gate. This results in a decay of the obtained signals for the correlator \({D}_{R}^{A}(t)\). The rate of the exponential decay grows roughly linearly with the weight of the measured operators (Extended Data Fig. 2). This scaling with operator weight can be captured by instead applying a single depolarizing channel at the end of the time evolution, with a per-site error probability of γt with an effective noise rate γ. This effective γ also scales roughly linear as a function of the single-qubit error rate per gate p (Extended Data Fig. 2).

Quantum simulations are constrained by the required number of samples and the simulation time needed to reach a certain target accuracy. These factors are crucial for determining the size of Hamiltonians that can be accessed for particular quantum hardware.