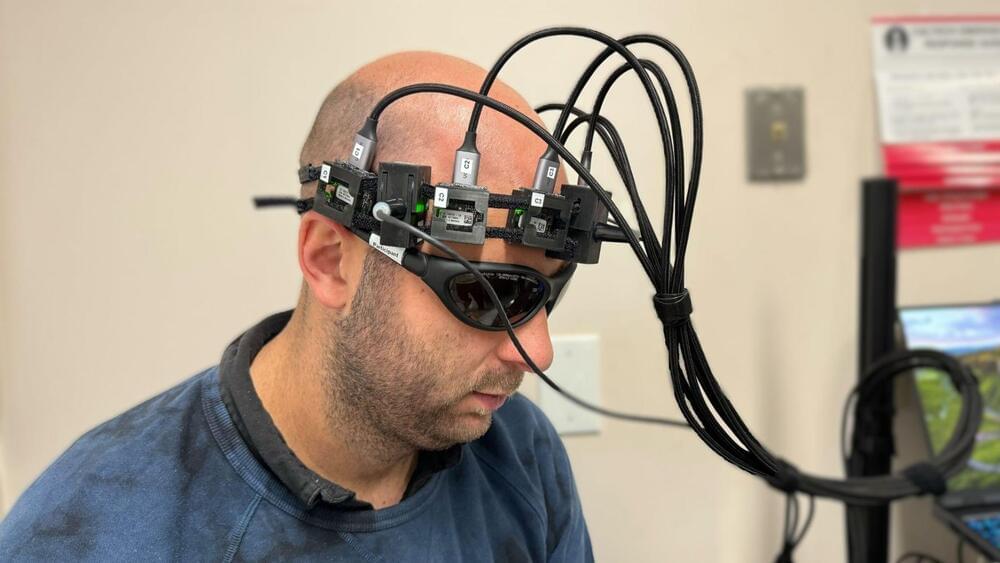

New steps have been taken towards a better understanding of the immediate and long-term impact of COVID-19 on the brain in the UK’s largest study to date.

Published in Nature Medicine, the study from researchers led by the University of Liverpool alongside King’s College London and the University of Cambridge as part of the COVID-CNS Consortium shows that 12–18 months after hospitalisation due to COVID-19, patients have worse cognitive function than matched control participants. Importantly, these findings correlate with reduced brain volume in key areas on MRI scans as well as evidence of abnormally high levels of brain injury proteins in the blood.

Strikingly, the post-COVID cognitive deficits seen in this study were equivalent to twenty years of normal ageing. It is important to emphasise that these were patients who had experienced COVID, requiring hospitalisation, and these results shouldn’t be too widely generalised to all people with lived experience of COVID. However, the scale of deficit in all the cognitive skills tested, and the links to brain injury in the brain scans and blood tests, provide the clearest evidence to date that COVID can have significant impacts on brain and mind health long after recovery from respiratory problems.