“We now need to continue observing this star to confirm the other candidate signals,” said Dr. Alejandro Suárez Mascareño. “But the discovery of this planet, along with other previous discoveries such as Proxima b and d, shows that our cosmic backyard is full of low-mass planets.”

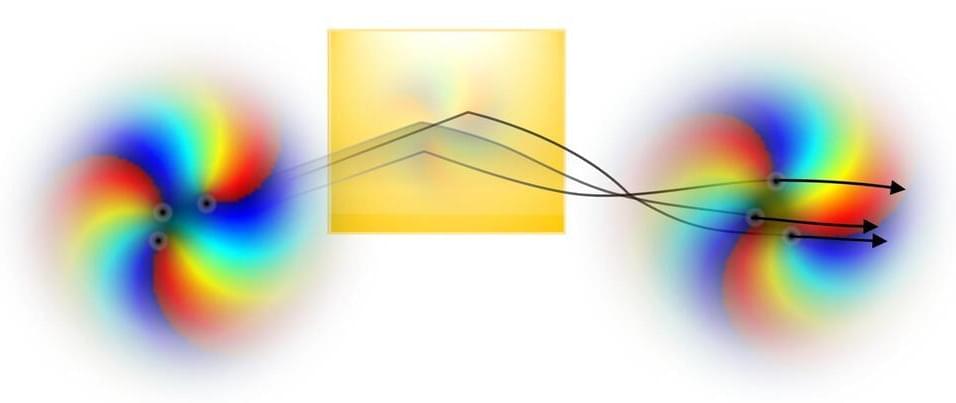

How close are Earth-sized exoplanets to Earth? This is what a recent study published in Astronomy & Astrophysics hopes to address as a large international team of researchers have announced the discovery of Barnard b, which orbits Barnard’s star approximately 6 light-years from Earth. This discovery is profound because Barnard’s star is the closest single star to Earth but also because Barnard b is estimated to be approximately just over one-third the mass of the Earth, or approximately three times the mass of the planet Mars.

Barnard’s star is approximately 16 percent the mass of our Sun with approximately 19 percent of its diameter. While the size of Barnard b poses the possibility that it might be Earth-like, its 3.15-day orbit puts it well inside its star’s habitable zone (HZ).

“Barnard b is one of the lowest-mass exoplanets known and one of the few known with a mass less than that of Earth. But the planet is too close to the host star, closer than the habitable zone,” said Dr. Jonay González Hernández, who is a researcher at the Instituto de Astrofísica de Canarias in Spain, and lead author of the study. “Even if the star is about 2,500 degrees cooler than our Sun, it is too hot there to maintain liquid water on the surface.”