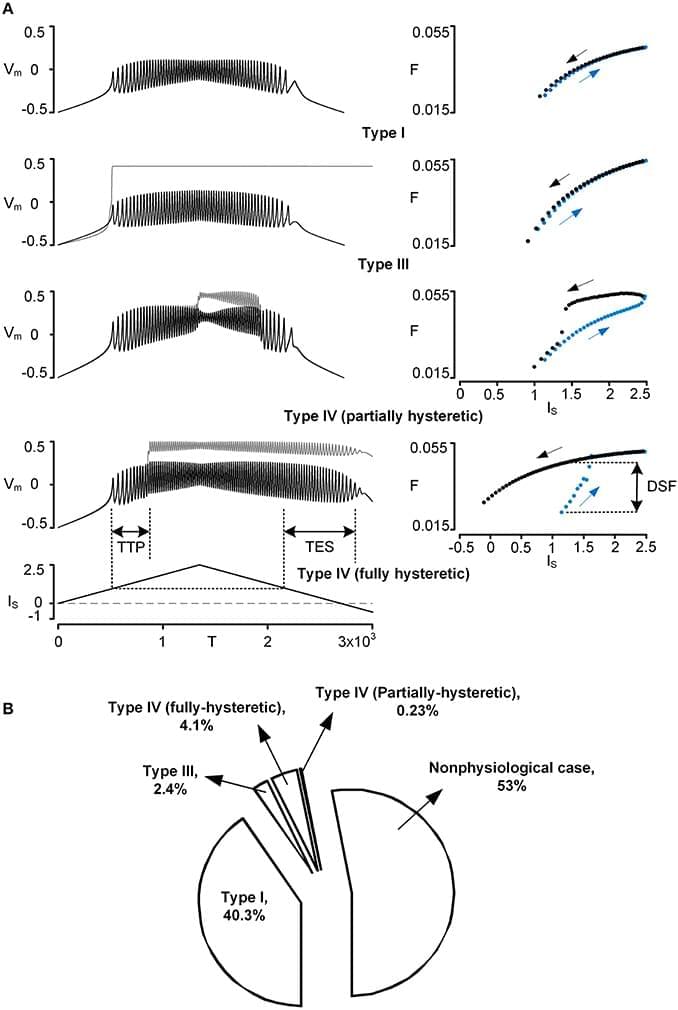

However, the effect of the PIC on firing outputs also depends on its location in the dendritic tree. To investigate the interaction between PIC neuromodulation and PIC location dependence, we used a two-compartment model that was biologically realistic in that it retains directional and frequency-dependent electrical coupling between the soma and the dendrites, as seen in multi-compartment models based on full anatomical reconstructions of motoneurons. Our two-compartment approach allowed us to systematically vary the coupling parameters between the soma and the dendrite to accurately reproduce the effect of location of the dendritic PIC on the generation of nonlinear (hysteretic) motoneuron firing patterns. Our results show that as a single parameter value for PIC activation was either increased or decreased by 20% from its default value, the solution space of the coupling parameter values for nonlinear firing outputs was drastically reduced by approximately 80%. As a result, the model tended to fire only in a linear mode at the majority of dendritic PIC sites. The same results were obtained when all parameters for the PIC activation simultaneously changed only by approximately ±10%. Our results suggest the democratization effect of neuromodulation: the neuromodulation by the brainstem systems may play a role in switching the motoneurons with PICs at different dendritic locations to a similar mode of firing by reducing the effect of the dendritic location of PICs on the firing behavior.

Spinal motoneurons have large, highly branched dendrites and voltage-gated ion channels that generate strong persistent inward currents (PICs) (Schwindt and Crill, 1980). Over the past 30 years, the impact of PICs on the firing output of the motoneurons has been extensively investigated in various species, including turtles (Hounsgaard and Kiehn, 1985, 1989), rats (Bennett et al., 2001; Li and Bennett, 2003), mice (Carlin et al., 2000; Meehan et al., 2010) and cats (Lee and Heckman, 1998, 1999). There has been a consensus in the motoneuron physiology community that in the presence of monoamines (i.e., norepinephrine and serotonin), the activation of the L-type Ca2+ PIC channels is facilitated, producing a long-lasting membrane depolarization (i.e., plateau potential) (reviewed in Powers and Binder, 2001; Heckman et al., 2008).