Never underestimate the power of a “do-over.”

Video gamers know exactly what I’m talking about: the ability to face a challenge over and over again, in most cases with a “reset” of the environment to the initial conditions of the fight (or trap, or puzzle, etc.). With a consistent situation and setting, the player is able to experiment with different strategies. Typically, the player will find the approach that works, succeed, then move on to the next challenge; occasionally, the player will try different winning strategies in order to find the one with the best results, putting the player in a better position to meet the next obstacle.

Real life, of course, doesn’t have do-overs. But one of the fascinating results of the increasing sophistication of virtual world and game environments is their ability to serve as proxies for the real world, allowing users to practice tasks and ideas in a sufficiently realistic setting that the results provide useful real life lessons. This capability is based upon virtual worlds being interactive systems, where one’s actions have consequences; these consequences, in turn, require new choices. The utility of the virtual world as a rehearsal system is dependent upon the plausibility of the underlying model of reality, but even simplified systems can elicit new insights.

The classic example of this is Sim City (which I’ve written about at length before), but with the so-called “serious games” movement, we’re seeing the overlap of gaming and rehearsal become increasingly common.

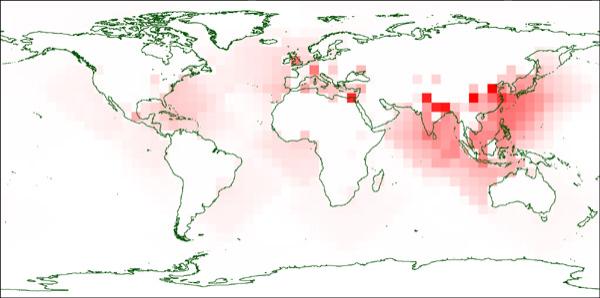

The latest example is particularly interesting to me. The United Nations International Strategy for Disaster Reduction group has teamed up with the UK game design studio Playerthree to create the Flash-based “Stop Disasters” game. The goal of the game is to reduce the harmful results of catastrophic natural events — the disaster that gets stopped isn’t the event itself, but its impact on human life.

The game mechanisms are fairly straightforward. The player chooses what kind of disaster is to be faced (earthquake, hurricane, tsunami, wildfire or flood), then has a limited amount of time to prepare for the inevitable. The player can build new buildings, retrofit or demolish old ones, install appropriate defensive infrastructure (such as mangroves along tsunami-prone shorelines or firebreaks around water towers), institute preparedness training, install sirens and evacuation signs, and so forth — all with a limited budget, and with ancillary goals that must be met for success, such as building schools and hospitals for community development, or bringing in hotels for local economic support.

Once the money is spent (or the time runs out), the preordained disaster strikes, and the player gets to see whether his or her choices were the right ones. At the easy level, there’s generally enough money to protect the small map and limited population; at the harder levels, the player must make difficult choices about who and what to save. The overall complexity reminds me of the very first version of Sim City, but don’t take that as a criticism: the first Sim City arguably offered the clearest demonstration of urban complexity of the four versions, in large measure because of its spartan interface and simplicity.

Stop Disasters is billed as a children’s game, and it’s true that the folks at Architecture for Humanity aren’t going to use it for planning purposes. That’s not the goal, of course. This isn’t a rehearsal tool for the people who have to plan for disasters, but for the people who have to live with that planning — and those people who will choose to help their communities during large-scale emergencies.

I suspect that there would be an audience for a more complex version of Stop Disasters, one which puts more demands on the player to accommodate citizen needs. It’s a bit too easy to simply demolish old buildings rather than retrofit them in the UN/ISDR game, for example, and I would love to see more economic tools. I’d also like to see a wider array of disasters, beyond the short, sharp, shock events of quakes and storms. What would a Stop Disaster global warming scenario look like, for example — not trying to prevent climate change, but to deal with its consequences?

If we really want to get our hands dirty, we’d need to build up Stop Disasters scenarios for the advent of molecular manufacturing, self-aware artificial intelligence, global pandemic, peak oil and asteroid strikes.

Not because such games would tell us what we should do, but because they’d help us see how our choices could play out — and, more importantly, they’d remind us that our choices matter.